Anarchy in the U.S.A.

Emma Goldman’s speech to an affluent club recalls a moment in American history when liberals fought for the First Amendment

In Out of the Fog, historical detective Brian Berger digs through newspaper columns, clippings, and other clues to bring readers the fascinating, scandalous, and forgotten tales of the past.

In an era when dissent and unpopular opinions are as likely to be suppressed by moralizing “liberals” (sic) as they are by censorious “conservatives,” it’s instructive to recall a period in American history when things were quite different.

It was the winter of 1916. Emma Goldman, the Red Queen of the Anarchist movement, had been invited to speak to the Civitas Club of Brooklyn, one of the best-known women’s clubs in the nation, whose blue-blooded, affluent members were not known for radicalism.

And yet, there it was in the local newspapers of Jan. 10: Two days hence, Goldman would come to the group’s home on tony Pierrepont Street in Brooklyn Heights to deliver a lecture titled “My Personal Interpretation of Anarchism,” with Mrs. Palmer Jadwin and Mrs. James P. Warbasse acting as club hostesses.

The sponsorship of Agnes Warbasse was significant, belying the rigid precepts of Brooklyn “society.” Her husband, Dr. Warbasse, was both a prominent surgeon and a socialist activist. Agnes shared his passions, and together they had six children and had recently co-founded the National Cooperative League to promote the development of consumer cooperation in the marketplace. While the class and ethnic divides between the Civitas Club and the city of millions of new immigrants were real, so too was the commitment of the Warbasse family in seeking the betterment of all.

But of course, socialism—let alone anarchism—had many opponents, including other Civitas Club members, and it’s likely they who made their displeasure known to the press.

To be sure, Goldman’s radical reputation was fully earned. Born Jewish in Kaunas, Lithuania, in 1869, when it was still part of the Russian Empire, Goldman emigrated to the United States in 1885, settling first in Rochester, New York. As she’d often explain, it was the Haymarket Square affair of May 4, 1886—a strike rally in Chicago that, after a small bomb exploded, turned into a deadly riot—and its subsequent trials, including the hanging of four likely innocent anarchists, that wholly radicalized her.

Goldman arrived in New York at a time, as Paul Berman has chronicled in Tablet, when anarchism was the city’s predominant ideology of political radicalism, especially among its immigrant Jews. Goldman became a disciple of German anarchist Johann Most and a lifelong intimate of Lithuanian-born Alexander Berkman, whose attempted assassination of Carnegie Steel Chairman Henry Clay Frick in July 1892 would earn him 14 years in prison. In 1893, Goldman herself began a year in Blackwell’s Island prison for inciting a riot in Union Square. Upon her release, Goldman supported herself with lectures, midwifery, and occasional other ventures, such as an ice cream shop in the then—circa 1895 or 1896—explosively growing Jewish ghetto of Brownsville, Brooklyn.

Goldman’s notoriety reached a peak after September 1901, when the anarchist Leon Czolgosz assassinated U.S. President William McKinley at the World’s Fair in Buffalo. Though Czolgosz had seen Goldman lecture in Cleveland and briefly spoke with her, there was no evidence that Goldman knew anything about his plans. Still, with the federal Anarchist Exclusion Act of 1903 signaling a period of government oppression, Goldman withdrew from public life until 1906, when she founded a magazine, Mother Earth. Among the publication’s favored causes were the rights of labor—working women, men, and children alike—free speech, free love, birth control and, in the 1910s, opposition to the capitalist war in Europe.

Despite Goldman’s anathema-to-some résumé, Civitas Club President Mrs. Edwin Quinn was quick to defend the group’s invitation. “Friends of mine have known Miss Goldman for 10 years,” she told a reporter, “and they tell me that she is a most interesting woman, well worth listening to. Robert Henri, the artist, told me that Miss Goldman is a fine, noble character, who has been greatly maligned by the newspapers. We are not setting up for anarchy—we are curious to know.”

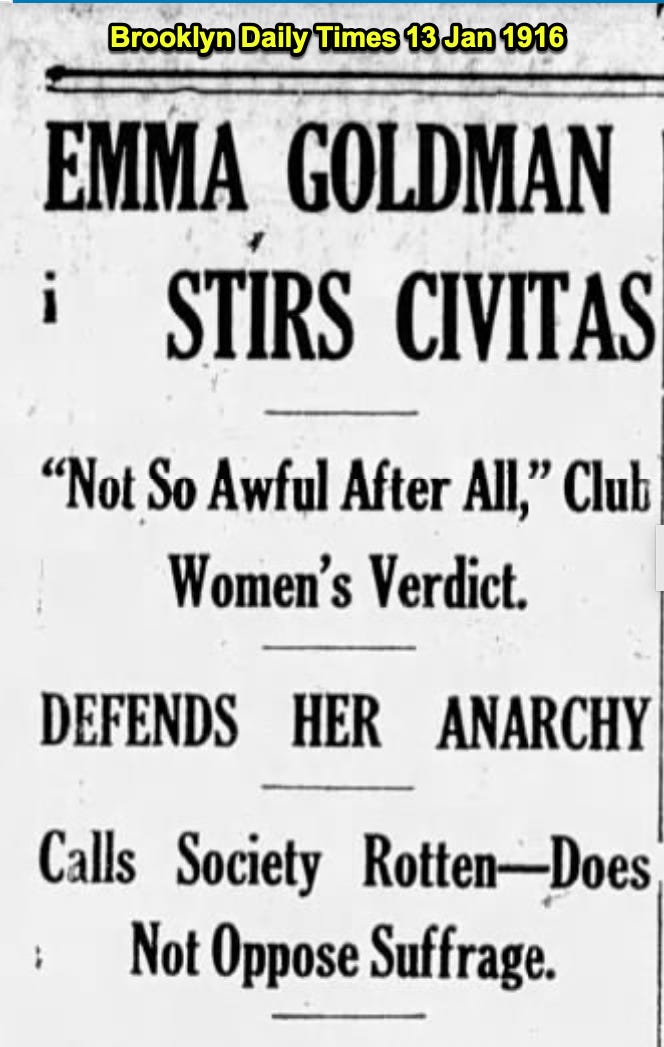

Though no complete transcript of Goldman’s speech has survived, contemporaneous newspaper accounts provide a portrait of her presentation. With a headline labeling her address “vitriolic,” The Brooklyn Eagle version began:

More than three hundred women listened to Emma Goldman … yesterday afternoon as she denounced society as rotten to the core, characterized the politician as a “crook or a tool,” excoriated the police force and oratorically bludgeoned private wealth. The cultured and bejeweled women winced when the apostle of anarchy unblushingly declared that children have as much right to born out of wedlock as under the sanction of church and state.

While the Brooklyn Standard similarly described Goldman as an “angry proselytizer,” the fact that her speech included quotations from Tolstoi, Oscar Wilde, Kropotkin, Ralph Waldo Emerson, Henry David Thoreau, and Ibsen suggests her address was loftier than a mere harangue. The Brooklyn Daily Times account seems the fairest: “Miss Goldman amazed her hearers with the latitude of her vocabulary, and with the vista which her anarchistic ideas opened for them. She apologized every time she used slang.”

Afterwards, Goldman took questions (she wasn’t opposed to women’s suffrage per se, she clarified, but “opposed the ballot as an accessory of governmental regulation”) and joined the club members for tea and cake. It was all quite polite and pleasant—so much so that Goldman confided to the Daily Times that she felt “like a lion among lambs.”

***

Still, this wasn’t enough for some, and various letters to the editor decried the Civitas Club for having granted Goldman a platform. Responding to this criticism, Mrs. Quinn emphasized that—as with the philosophy of Jean-Jacque Rousseau—she found Goldman’s ideas more interesting than practicable. She offered no apology for providing the famous anarchist with a platform to speak.

“Let me read you a few sentences from our constitution,” Mrs. Quinn told an Eagle reporter. “The object of this club is to awaken interest in civic and social welfare, and to further all movements that aim to advance human progress.

“And since the primary object of our club is not social, it is obvious that we did not invite Emma Goldman because we wanted to be entertained. Any subject that is of present-day interest to humanity we consider necessary to discuss in our club. And anarchy is a recognized element of society today. And to turn away from it without knowing the facts would be both stupid and unscientific.”

Marvelous posting. Emma Goldman was a most interesting and brave woman. and a “lion among lambs” indeed!

Good stuff from Mr.Berger as always.