April 5, 2024: Iron-Clad BS

IDF fires two over WCK disaster; Hamas' ‘last promise’; Eastman, Clark risk disbarment

The Big Story

Yesterday, following President Joe Biden’s call for an “immediate cease-fire” in Gaza, we wrote that we expected “various Biden minions to announce that there’s been ‘no change in policy’ and that their support for Israel is as strong as ever.” Well, here was White House national security spokesman John Kirby in an exchange with Fox News’ Peter Doocy yesterday:

DOOCY: On October 7, President Biden said, “My administration’s support for Israel’s security is rock-solid and unwavering.” That is not true anymore, correct?

KIRBY: No, it is true. It’s still true today.

DOOCY: How is his support “unwavering” but you’re also reconsidering policy choices?

KIRBY: Both can be true.

DOOCY: They cannot be true! They are completely different things! He is wavering. How is he not wavering?

KIRBY: No, no, no, come on, now. … [Biden] made clear in his call to the prime minister that our support for Israel’s self-defense remains iron-clad. (Emphasis added.)

Iron-clad, by the way, appears to be one of the administration’s favorite buzzwords for when it’s screwing over the Israelis. When, on March 25, the United States refused to a veto a U.N. Security Council resolution calling for an immediate cease-fire in Gaza, the White House line was that it was “perplexed” by the Israelis’ anger, since National Security Advisor Jake Sullivan had just conveyed to Israeli Defense Minister Yoav Gallant Biden’s “iron-clad support for Israel’s security and defense against all threats.”

So, with the waters now sufficiently muddied, what is actually happening? Netanyahu’s office announced on Friday that following the call with Biden, the Israeli security cabinet approved a plan to rapidly increase the flow of aid into Gaza. Israel will open the Ashdod Port and the Erez Crossing for humanitarian deliveries and will step up the amount of aid from Jordan delivered through the Kerem Shalom crossing into Gaza. In response, U.S. Secretary of State Antony Blinken said Friday that “the proof is in the results” and that the United States would be “closely looking” at metrics such as the evolution of famine risk.

The famine metrics are a nice illustration of the trap the White House has set for Israel. As Salo Aizenberg has pointed out on X, the famine metrics put out by the United Nations and international NGOs are, at best, unreliable. To list just a few of the problems and inconsistencies Aizenberg has identified:

According to United Nations and Israeli numbers, Israel is already delivering twice the amount of food into Gaza than what the U.N. World Food Program (WFP) says is necessary to meet Gazan civilians’ needs.

The United Nations has been predicting “imminent famine” since Oct. 13 and yet has constantly shifted the date at which Gazans will begin to starve. On Jan. 23, an UNRWA official declared that 500,000 people in Gaza were already facing “catastrophic hunger.” But on March 18, a U.N. NGO released a report projecting that 300,000 people in northern Gaza would face famine conditions by the end of May, while 1.1 million people could face an “extreme lack of food” by mid-July.

The numbers keep changing. On Dec. 9, for instance, the deputy director of the WFP said that “half” of Gazans were “starving.” Less than two weeks later, the WFP claimed that “25%” of Gazans were on the “brink” of starvation. On Jan. 1, the United Nations was again warning that “half” of Gazans were at “risk” of starving.

There is also ample evidence in the form of photos and videos, many of them collected by X user @Imshin, of fully stocked food markets in central and southern Gaza.

But let’s simply concede that many Gazans are facing food insecurity, even if the true extent is difficult to calculate. The problem is not that food isn’t getting into Gaza but that it is not being adequately distributed once it reaches Gaza. This is due to the wartime collapse of Hamas’ civil infrastructure—especially in the north—and the well-documented looting and hoarding on the part of Hamas and various armed Palestinian gangs, with the latter stealing the food to sell it at inflated prices on the black market. More aid trucks will not fix this basic distribution problem.

Which brings us to the question, How could Israel address this? One obvious way would be to evacuate civilians to Egypt or to some other safe third country—except that the United States has explicitly ruled out what it calls “the forced relocation of Palestinians,” which in any other conflict would be called the evacuation of civilians from a war zone. The other solution would be to adopt the counterinsurgency doctrine practiced by the United States in its wars in Iraq and Afghanistan: “clear, hold, and build.” In other words, the IDF would go in—on the ground and in strength—in order to clear Gaza of Hamas, hold Gaza against Hamas’ attempts to reconstitute itself, and then begin to build by providing basic services, including food distribution (former U.S. Gen. David Petraeus has recommended this). But the United States has also explicitly ruled this out, with Kirby stating in November that Biden is opposed to any “reoccupation by Israeli forces of Gaza.” American officials have instead repeatedly told the Israelis, first in northern Gaza and now with respect to Rafah, that they should avoid ground operations and focus on “surgical” strikes against Hamas leadership.

We noted yesterday that Obama-Biden surrogates such as Ben Rhodes and Richard Haass were insinuating that Israel wanted 2,000-pound bunker busters to indiscriminately kill civilians, despite the U.S. Air Force using these exact weapons in Mosul, Iraq, and Raqqa, Syria, to protect civilians while targeting ISIS’ tunnel infrastructure (bunker busters, because they are designed to explode underground, reduce the risk of collateral damage). We’ve also noted that U.S. outrage over the World Central Kitchen (WCK) convoy strikes, which has included official insinuations that the IDF is deliberately murdering aid workers, has ignored the long history of similar incidents from the U.S. military, which were in many cases even more egregious.

But these specifics are only part of a more general pattern: The United States is demanding that Israel fix problems while ruling out all the ways the United States would attempt to fix those same problems if it were in Israel’s place. If it doesn’t make sense, that’s because it’s not supposed to make sense. The point is to set impossible demands and then blame Israel for failing to meet them. That way, when the administration stabs its ally in the back, as it has wanted to do since the current war began, it will be able to throw up its hands and blame “Bibi.”

IN THE BACK PAGES: On the 20th anniversary of Saul Bellow’s death, David Mikics celebrates the great Jewish-American novelist

The Rest

→The IDF will fire two senior officers and formally censure several others for their roles in the Monday strikes on the WCK aid convoy. According to the Israeli probe into the incident, which was presented to IDF Chief of Staff Herzi Halevi on Thursday, the strike was ordered against the vehicles “after officers suspected they carried a Hamas gunman, despite a low level of confidence, and against army regulations.” The probe found that the IDF officers who ordered the strike were not aware that the vehicles belonged to WCK.

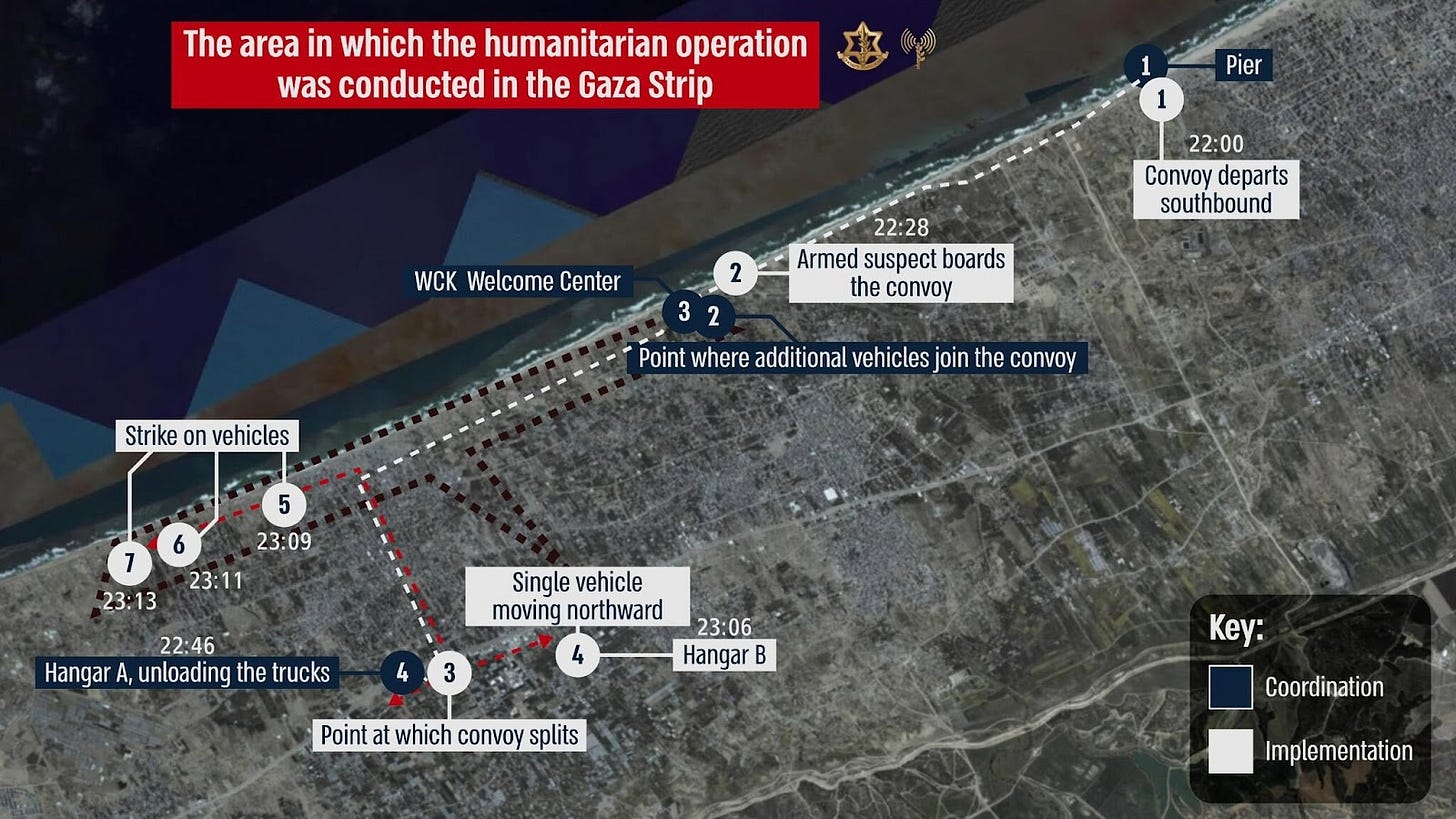

Here’s a rough timeline of what happened on Monday, taken from The Times of Israel’s write-up of the probe, along with a map provided by the IDF:

As the convoy traveled toward the dropoff point for the aid, “Hangar A,” troops identified one gunman climbing on the roof of one of the trucks on the convoy and appearing to open fire with an automatic weapon. The identity of this gunman is unknown, and he got off when the convoy arrived. The IDF division command attempted to contact the convoy through a WCK employee in Europe, but the employee could not reach the team on the ground.

At Hangar A, an Israeli drone identified a crowd of 15 to 20 people, at least two of whom were allegedly armed. IDF officers identified these gunmen as Hamas but were ordered by their division commander not to strike them due to their proximity to the convoy.

Shortly before the convoy left, an IDF commander mistakenly identified a gunman entering one of the escort cars. Drone footage reviewed during the probe appeared to show the suspect holding a bag, not a gun.

Believing that one of the vehicles was carrying a gunman, someone—it is not clear who—ordered a drone strike. Two subsequent strikes were ordered against the other vehicles in the convoy, despite no indication that they were carrying gunmen, “which was a violation of IDF procedures.”

The probe also found that while the WCK’s route had been coordinated with the IDF, this information “was not passed down from senior commanders to the officers on the ground, who ultimately called in the attack.”

The IDF concluded that the attack was “a serious mistake, which stemmed from a serious failure, as a result of wrong identification, a mistake in decision-making, and an attack contrary to the orders and open-fire regulations.” In response to the probe’s findings, Halevi ordered the removal of the chief of staff of the Nahal Infantry Brigade and the brigade’s firepower coordination officer and formally reprimanded the commander of the Southern Command, Maj. Gen. Yaron Finkelman, as well as the commander of the 162nd Division and the commander of the Nahal Brigade.

→In a Haaretz essay published today, Israeli journalist Shlomi Eldar traveled to Cairo to speak with well-connected Palestinian refugees living there, many of them former leaders of Fatah. Keeping in mind the normal caveats that apply when one Palestinian faction is attempting to discredit another, the refugees made some interesting remarks about the Hamas leadership’s thinking in the years leading up to Oct. 7. For instance, here’s Sufyan Abu Zaydeh, a former Palestinian Authority minister:

Abu Zaydeh is well aware that for the past two years the Hamas leadership had been talking about implementing “the last promise” (alwaed al’akhir)—a divine promise regarding the end of days, when all human beings will accept Islam. [Hamas Gaza leader Yahya] Sinwar and his circle ascribed an extreme and literal meaning to the notion of “the promise,” a belief that pervaded all their messages: in speeches, sermons, lectures in schools and universities. The cardinal theme was the implementation of the last promise, which included the forced conversion of all heretics to Islam, or their killing.

And here’s a former “high-ranking” Fatah official who goes in the story by the name of “Iyad”:

When [Hamas] started talking about “the last promise,” he too didn’t think it was serious. But in 2021, his opinion changed. By then Iyad realized that this wasn’t some off-the-wall idea propounded by a coterie of “wild weeds” but that the entire leadership had been taken captive by the Sinwar group’s deranged idea of an all-out battle. They had an orderly plan and they believed they were fulfilling a divinely ordained mission.

“So strongly did they believe in the idea that Allah was with them, and that they were going to bring Israel down, that they started dividing Israel into cantons, for the day after the conquest.”

Iyad describes an astonishing event, which demonstrates the scale of the madness in Hamas. “One day, a well-known Hamas figure calls and tells me with pride and joy that they are preparing a full list of committee heads for the cantons that will be created in Palestine. He offers me the chairmanship of the Zarnuqa committee, where my family lived before 1948.”

The Arab village of Zarnuqa lay about 10 kilometers southwest of Ramle; today the Kiryat Moshe neighborhood of Rehovot stands on its land. Iyad was being informed that he would lead the group that would be in charge of rehabilitating the Ramle-Rehovot area on the day after the realization of “the last promise.”

The article also discusses a conference, “The Promise of the Hereafter,” held at the Commodore Hotel in Gaza in September 2021, in which attendees drew up detailed plans to administer Israel “apartments and institutions, educational institutions and schools, gas stations, power stations and sewage systems” following Hamas’ imminent conquest. They also discussed brain drain, concluding that “educated Jews and experts … should not be allowed to leave and take with them the knowledge and experience they acquired while living in our land.”

→The New York Times published an opinion essay on Friday, “Is This the End of Academic Freedom?,” from two NYU professors who argued that the university’s “repression” of pro-Palestinian activism on campus “violates the very foundations of academic freedom.” While NYU’s anti-Israel activists haven’t seemed particularly repressed to us, let’s put that aside for a moment. As Compact’s Geoff Shullenberger noted on X, one of the authors of the essay, Paula Chakravartty, was also a co-signatory of a fall 2020 letter to the NYU provost demanding that the university investigate her colleague, Mark Crispin Miller.

What was Miller’s crime? In a discussion on NYU’s mask mandate during a meeting of his class on propaganda, Miller had urged his students to look up randomized control trials showing that masking did not prevent the spread of COVID-19. A student in the class took to Twitter to demand Miller be fired for “spouting dangerous rhetoric that serves to cultivate fear and confusion during a pandemic.” Miller then wrote a blog post defending his own conduct in the class, in which he linked to the student’s Twitter thread. According to the faculty letter signed by Chakravartty, this made Miller guilty of “intimidation tactics, abuses of authority, aggressions and microaggressions, and explicit hate speech, none of which are excused by academic freedom.” The letter concluded, “It is unacceptable to remain silent in the face of ongoing harm to our students.” We wonder what made them change their minds.

→A Washington, D.C., Bar panel has issued a “nonbinding” preliminary ruling that former Trump Department of Justice official Jeffrey Clark—who drafted a letter, which was never sent, to Georgia Gov. Brian Kemp claiming that the DOJ was “investigating various irregularities” surrounding the 2020 election—violated professional ethics rules and could face disbarment. The ruling comes a little over one week after a California judge ruled that John Eastman, the legal architect behind Trump’s efforts to challenge the 2020 election results, should also face disbarment.

Eastman and Clark were active in helping Trump to formulate legal strategies to challenge the election results and certification in 2020. But whatever you think of the wisdom of those efforts, the disbarment efforts stink of gratuitous lawfare targeting partisan opponents. Both rulings rest on the argument that because experts and mainstream media sources agree there was no fraud or irregularity in the most chaotic election of our lifetimes, Eastman and Clark’s claims of potential fraud or irregularity in the immediate aftermath of the election were intentional lies. That’s despite, for instance, a Fulton County, Georgia, Elections Board member testifying at Clark’s disciplinary hearing this week that there had been no signature verification on 147,000 mail-in ballots and no chain-of-custody documentation for mail-in ballots or drop boxes, both of which were required by Georgia law. No matter—the government said there was no fraud, and so no lawyer is allowed to have believed, between November 2020 and January 2021, that there could have been.

Read it here: https://www.wsj.com/economy/jobs/unemployment-jobs-report-us-immigration-surge-8e260f47

TODAY IN TABLET:

The American Left’s Milošević Moment, by Andrew Nutting

The incitement of tribal hatreds and historical grievances under the cover of Marxist-Leninist language led to the destruction of the multiethnic country of Yugoslavia and the genocide of Bosnian Muslims. The parallels to American wokeism are hard to ignore.

SCROLL TIP LINE: Have a lead on a story or something going on in your workplace, school, congregation, or social scene that you want to tell us about? Send your tips, comments, questions, and suggestions to scroll@tabletmag.com.

God, How We Miss Saul Bellow

Nearly 20 years after the great Jewish and American novelist’s death, we have never been more in need of his thirst for life

By David Mikics

Saul Bellow, who passed away this day in 2005, once the most celebrated of late-20th-century American writers, is now barely taught in universities, disdained as an out-of-date fogey with, we are told, conservative-adjacent hang-ups. But readers will always return to Bellow. Every so often I meet people whose faces light up when they discover I have written about him. Bellow, they tell me, lifted them out of the doldrums and into the clouds. Bellow’s tenacious desire for more life, passed on so readily to readers, never disappoints, and so it will never be lost to a discerning reading public.

Gerald Sorin’s new biography, Saul Bellow, draws its subtitle from a Bellow interview: “I was a Jew and an American and a writer.” Chronologically, the sentence holds true. Bellow, who was born in Lachine, Quebec, in 1915 to a Yiddish-speaking household, was a Jew before he became an American. When he was 8 the family moved to Chicago, where his father was a bootlegger and also ran a coal yard. Bellow’s writing career was scorned by his father and brothers, who saw him, Saul said, as a “schmuck with a pen.” What he should have been was a money Jew, a businessman like his elder brother Maury, who rubbed elbows with gangsters.

“To be a Jew in the twentieth century / Is to be offered a gift,” the poet Muriel Rukeyser wrote in 1944 (lines that Sorin uses for his epigraph). Rukeyser produced this sentence during the most disastrous year for Jews in all of history. Yet she saw Jewishness as a gift rather than a curse, even in the midst of the Shoah, that black cloud of doom. So did Bellow, who published his first novel, Dangling Man, that same year.

Sorin says accurately that Bellow’s Jewishness was the germ of his being. Being born Jewish, Bellow once remarked, was “a piece of good fortune with which one doesn’t quarrel.” These days Jewishness is often seen as obligatory, an all-too-serious matter. For Bellow, it was a pleasurable stroke of luck.

Yet “when people call you a ‘Jewish writer’ it’s a way of setting you aside,” Bellow added. He stridently opposed Jewish schmaltz and the hawking of folkloric wares and shtetl nostalgia. Jewishness was about being an intellectual or a macher. Bellow thrived on the high-wire arguments of the Partisan Review crowd, including his doomed friend Delmore Schwartz, whom he memorialized as Von Humboldt Fleisher in Humboldt’s Gift. Humboldt had the heiresses of Henry James down cold, and he could talk for hours about the Rockefellers, Harry Thaw, and Evelyn Nesbit, modern poetry, opera, and baseball. At the end of his writing career Bellow paid tribute to another close friend, the tireless philosopher Allan Bloom, in Ravelstein. Abe Ravelstein, with his runaway zest for life, buys expensive Lanvin suits and burns cigarette holes in them, gossips eagerly about his students, ardently watches the Chicago Bulls, and expects everyone, just like him, to be jolted into awareness by Plato and Rousseau.

“Somber, heavy, growling, lowbrow” Chicago, Bellow called the city that shaped him. He cut his teeth on that dour Midwestern master, Theodore Dreiser; his early novel The Victim features a Dreiserian character, Asa Leventhal. Asa is grubby, desperate, devoid of interesting or creative thoughts, and fearful of hitting bottom. He is afraid he’ll end up one of “the lost, the outcast, the overcome, the effaced, the ruined,” like Dreiser’s Hurstwood. The Victim, an earnest, accomplished depiction of a Jew, Asa, persecuted by his antisemitic Doppelgänger, reads like a fever dream.

After The Victim, though, Bellow’s lively brand of writing occupied the opposite end of the spectrum from Midwestern naturalism, the hard-as-iron aesthetic of Dreiser, Stephen Crane, and Frank Norris. These authors transmitted the grim messages of fate, but Bellow wanted to be “the representative of beauty, the interpreter of the human heart, the hero of ingenuity, playfulness, personal freedom, generosity and love.” Not until The Adventures of Augie March, his third novel, published in 1953, does Bellow break through into playfulness; his first two books are tight-lipped and constrained.

Bellow can communicate like few other fiction writers the sheer jostling thrill of living, breathing, arguing, seducing, and most of all—a Bellow specialty—sizing up the people and things around you. In an interview quoted by Sorin, Bellow commented,

I think I had a kind of infinite excitement going through me, of being a part of this, of having appeared on this earth. I always had a feeling ... that this is a most important thing, and delicious, ravishing, and nothing happened that was not of deepest meaning for you—a green plush sofa falling apart, or sawdust coming out of the sofa, or the carpet it fell on ... everything is yours, really.

Such excitement is carried by Henderson, the “absurd seeker of higher qualities,” in Bellow’s favorite among his own books, Henderson the Rain King, as well as by Augie March, who exults, “Look at me, going everywhere!”

The excitement was also about Jewishness, beginning with the book of Genesis, which Bellow studied in heder. “I was four years old and my head was in a spin,” he remarked. “I would come out of [the rabbi Shikka Stein’s] apartment and sit on the curb and think it all over in front of my house.” The biblical characters seemed like his own relatives, hot-headed, shrewd, and passionate bearers of mystery.

Bellow spoke a fine Yiddish until his last days. He grew up in the language, and never ceased cherishing its nuances. He remembered childhood days going to the movies in Chicago, when there was “a low rumbling in the theatre, that of dozens of child translators, himself included, whispering Yiddish to their mothers.” Yet, he admitted, he rarely picked up a Yiddish book as a grown-up. His future, he knew from early on, was in the American language that was spoken on-screen and in the streets.

Bellow once remarked that he had taken something from Sholem Aleichem and the other great Yiddish tale-tellers—a conjunction of sadness and laughter, and a love of funny, bittersweet occasions. Yet Bellow’s uproarious ironies are written on a much larger scale. His ambitions were as huge as Eugene Henderson’s physique, while the Yiddish short story writers remained miniaturists. Moreover, for Bellow to write in Yiddish would have meant isolating himself from the mainstream, and falling under the limiting curse of the “Jewish writer.”

When Bellow began writing, in the ‘40s, Hemingway ruled the roost of American fiction. Too many young writers were compelled to emulate his taut existential ethos. Hemingway’s heroes felt at most a hard stoic joy, and that only rarely. They were chastened survivors of a battle with life. It was in the break with Hemingway that Bellow helped change the shape and texture of American prose.

Bellow’s Augie March was exuberant, rough and ready. A cosmic optimism radiated through this big ungainly book, not altogether unlike the hopped-up thrills that Kerouac was to deliver with On the Road four years later. In one of Augie’s scenes Bellow actually sounds like a Beat writer, when the hero and his Mexican friend Padilla sleep with two hard-up African American women. But the clipped, ambivalence-free diction of a Kerouac (who must have read Augie) doesn’t suit Bellow, and the scene falls flat.

Augie March is a grand, flawed book, complete with stray-dog Miltonic similes and Melville-like arias that careen down the page. Augie is too unformed to be as passionately driven as Bellow claims he is, and some of Bellow’s proclamations about life force sound bald and unconvincing. But anyone who wades into Augie’s multitudinous pages is in for a treat. Here is one instance, Bellow’s portrait of Five Properties (a character based on Bellow’s brother Maury, and so nicknamed because, when pitching to girls, he boasts about his real estate):

That would be Five Properties shambling through the cottage, Anna’s immense brother, long armed and humped, his head grown off the thick band of muscle as original as a bole on his back, hair tender and greenish brown, eyes completely green, clear, estimating, primitive, and sardonic, an Eskimo smile of primitive simplicity opening on Eskimo teeth buried in high gums, kidding, gleeful, and unfrank; a big-footed contender for wealth.

See with what skill Bellow plants the odd word “original,” and how he provides that superb Whitmanian string of adjectives: “clear, estimating, primitive, and sardonic”! Five Properties’ Cyclops-like primitive nature and his cunning form a savory, unsettling mixture. This seemingly oafish but shrewd character embodies a kind of strategizing more full-blooded than could ever be deployed by the personages that Henry James creates, with their ballet-ish tip-toeing and peering into corners. Bellow draws on Jewish acuity and Chicagoan bluntness of manners to serve up an ace vignette, one of many in the book.

Augie, who ventures all over, winds up nowhere in particular. In the novel’s final pages he is stranded on the fields of Normandy, his car broken down. He has a new girl named Stella, and he dreams of settling down, though we somehow doubt he will. Augie neither makes his fortune nor is he broken on the wheel.

Moses Herzog, hero of Bellow’s breakthrough bestseller Herzog (1964), is to any objective eye, a failure. Crushed by his wife’s affair with his best friend (an episode Bellow transplanted from his own life), Herzog is rattled and worry-haunted. His house in the Berkshires is falling apart, with creaky rafters and a flooded basement. His life’s work, a book on Romanticism, is an inert heap of paper that will never be published. Everything seems to be rotting away, and Herzog might as well be squatting on the windowsill like Eliot’s gargoylish Jew in “Gerontion.” Yet the book ends on a note of fierce joy. In spite of it all, Herzog chooses life.

All through the novel Herzog relishes the vitality of his young daughter, the seductiveness of women, and even the energetic self-promoting shtick of his amorous rival, Valentine Gersbach, who is based on Bellow’s onetime friend Jack Ludwig. Herzog has interludes of unrelieved grimness, like a glimpse of a Chicago courtroom where Herzog witnesses the trial of a couple who have murdered their child. Here Bellow presages his gloomiest book, The Dean’s December, a dark masterpiece that pairs the forsaken ghettos of Chicago with the bleakness of communist Romania. Yet Herzog bounces back from his journey to the underworld. He does not deny the spiritual deprivation that makes life hell for some of us, but he knows that he wants to live.

Such a katabasis, as the Greeks called the trip to the underworld, features in other Bellow novels, like Mr. Sammler’s Planet, whose hero, during the Holocaust, crawled out from under a pile of corpses, having endured evils hardly imaginable. But the novel has its bright side too, speckled with portraits of ‘60s goofballs, like Sammler’s hippieish relatives Wallace and Angela. There is also Sammler’s nephew Elya, who likes to get on a plane to Israel and stride into the King David Hotel with no luggage—an irrepressible Jew who naturally stands up for others, and himself too.

Bellow frequently denounced the modernist viewpoint which sees the world as corrupt and valueless, with the alienated artist as hero standing against this modern spiritual desert. But he had another target as well, the notion that we must focus on worldly accomplishment, our noses ever to the grindstone.

Moses Herzog remarks, “The life of every citizen is becoming a business. This it seems to me, is one of the worst interpretations of the meaning of human life history has ever seen.” Americans often see life as a business, to be conducted with sober intent. One chief reason to read Bellow now is to disabuse oneself of the awful fixation on achievement that plagues what remains of our culture. Herzog is a failure, and so what? With his weird, unaccountable gladness he beats out the eager and calculating strivers, our intended role models.

Bellow treasured what he called “that mixture of imagination and stupidity with which people met the American Experience” (another line quoted by Sorin). We are more interesting for our flaws, flops, and spectacular faux pas, than for our shining successes.

The streets of Chicago were “raw, vulgar dynamic and dramatic,” Bellow said. He stayed true to those streets, their drama and dynamism, even though he often wrote about professors and intellectuals. But the hardnosed brutal calculus of Chicago existence never took over Bellow. Cutthroat devotion to the bottom line was simply not his way. He said,

There was not a chance in the world that Chicago, with the agreement of my eagerly Americanizing extended family, would make me in its own image. Before I was capable of thinking clearly, my resistance to its material weight took the form of obstinacy. I couldn’t say why I would not allow myself to become the product of an environment. But gainfulness, utility, prudence, business had no hold on me.

Long live the sheer imaginative power that marks pretty much every page that Saul Bellow wrote, along with the obstinacy, nuttiness, and pertinacity of his characters. The novelist Jeffrey Eugenides once said that he kept a copy of Herzog by his bedside, frequently opening it at random so he could glory in a Bellovian paragraph or two. Try it yourself, reader, and feel Bellow’s exhilaration going straight from the page to you.

Biden’s policy is a trap designed to make Israel feed a population that it is its enemy and far from starving and if deprived of food that is the sole responsibility and fault of Hamas . No war was ever won by feeding your enemy during the course of a war

Another superb column: highly informative and elegantly written. Deserves wider exposure.