April 8: Did Bibi Whiff With Trump?

104% tariffs on China; A primer on economic blitzkrieg; "Peter Retarrdo"

The Big Story

Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu met with President Donald Trump in the Oval Office on Monday. According to reports in the Israeli press, Bibi came to Washington looking for two things: relief on the 17% tariffs on Israeli imports that Trump announced last week, and U.S. approval for a strike on Iran’s nuclear facilities. He got neither, and received what appeared to be three unpleasant surprises to boot.

First, the big news: Trump announced that his administration was in “direct” talks with Iran and that a “big meeting” would take place on Saturday. Here was what the president said:

We’re having direct talks with Iran. They’ve started. It’ll go on Saturday, they have a very big meeting, and we’ll see what will happen. I think everyone agrees that doing a deal would be preferable to doing the obvious. And the obvious is not something that I want to be involved with or, frankly, that Israel wants to be involved with if they can avoid it. So we’re going to see if we can avoid it. But it’s getting to be very dangerous territory. … If the talks aren’t successful with Iran, I think Iran is going to be in great danger. You know, it’s not a complicated formula. Iran cannot have a nuclear weapon.

Subsequent reporting confirmed that the talks will occur in Oman and that they will be led, on the U.S. side, by Middle East envoy Steve Witkoff. “Witkoff and Vice President [J.D.] Vance … believe a deal with Iran is possible and preferable,” a “source familiar with their thinking” (i.e., someone in the Witkoff camp) told Axios’ Barak Ravid. Morgan Ortagus—who is theoretically Witkoff’s “deputy” but is in reality running her own foreign policy shop, sources tell us—separately told Al Arabiya that “we’re not going to get into the Biden trap where you do indirect talks that last for years and the Iranians just string us along. If we’re going to have talks, they need to be quick [and] they need to be serious about dismantling their nuclear weapons program.”

Despite the diplomatic overtures, the United States is continuing to move military assets to the Middle East. And the Iranians are continuing to demand sanctions relief as a precondition for talks, waving around nuclear threats, and insisting they won’t consider anything other than a return to the same Iran deal that Trump already trashed. That suggests to us that Witkoff and his nice-guy, can’t-we-all-get-along routine may represent a version of the first “messenger” in this Trump clip from 2012—i.e., the guy asking nicely, while a second messenger (Trump) threatens to drop the bombs:

Second, Netanyahu failed to secure any commitment from Trump on tariff relief and had to sit and grin through some of Trump’s ribbing about how much money the United States sends to Israel.

Third, in comments that have been seized on in the Israeli press and across pro-Israel social media, Trump had kind words to say about Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan, who has been a fire hose of belligerently anti-Israel rhetoric over the past month as Israeli and Turkish interests have clashed in Syria. Here was Trump:

I said to [Erdogan], “Congratulations, you’ve been able to do what no one has been able to do for 2,000 years, you’ve taken over Syria!” With different names, but same thing. I said, “You’ve taken it over through surrogates,” and he goes, “No, no, no, it was not me.” I say it was you, but that’s ok. … But look, [Erdogan’s] a tough guy, and he’s very smart, and he did something that nobody was able to do, you know, you gotta hand it to him.

Any problem that you [Netanyahu] have with Turkey, I think I can solve—as long as you’re reasonable. We have to be reasonable.

The horror! Except, wait—mediating between its fractious allies in the region is exactly what the United States is supposed to do and represents a welcome departure from the Obama-Biden model of kneecapping America’s allies while strengthening its enemies. As the Hudson Institute’s Michael Doran told The Scroll, “The chance that Israel and Turkey, left to their own devices, will find a modus vivendi in Syria is small. Only America can buffer between its two allies. From Trump’s inauguration until now, the administration has been busy with other issues, and Syria has not been on the radar of the White House. It is good to see the president taking an interest.”

Tablet News Editor Tony Badran added:

In contrast with his predecessors, President Trump views the Middle East not through the lens of “ideology,” or “minorities” and “communities,” or “substate actors.” Rather, he sees states and territories. In that, his approach to the geopolitics of the region is both fundamentally sound and historically grounded. You could pull a map of Syria dating back more than 3,000 years, and you’ll find a line demarcating spheres of influence between the dominant power in the north (geographic Turkey) and its analogue in the south (then Egypt, today Israel). Often, this division would be the result of a stalemate.

In this case, Israel and Turkey are both regional powers allied with the American global superpower. The ideal situation, from the American vantage point, is to help both states arrive at an understanding that safeguards their national security imperatives and clarifies corresponding geographical lines marking spheres of influence. Israel has no interest (or reach) in dictating politics in Syria or to secure economic agreements with its new government. Its interests are strictly security-based. Moreover, both Israel and Turkey share the interest of keeping Iran from reconstituting its influence in Syria—which happens to be the overriding U.S. interest in the country. The president’s comments indicate that this is precisely how he sees it. The U.S. role, therefore, is to manage these two important allies, hold them back from overreaching, and keep everyone’s eyes on the ball and pulling in the right direction.

So, was it a great trip for Bibi? No. At this point, it seems clear that Netanyahu had a much clearer idea of how to deal with Biden than with Trump, which is true of most leaders in the world, save possibly the prime minister of Japan. But was it a disaster? No, not remotely. Tariffs should be worked out in time, Trump is taking a welcome interest in smoothing the Israeli-Turkish relationship, and U.S. action on Iran could still be on the table. And if it’s not? Well, then Bibi will be back in the position he was before the November election—that if you need something done, you may have to do it yourself.

—Park MacDougald

IN THE BACK PAGES: Michael Doran on Trump and the “Restraintists”

The Rest

→Trump plans to move ahead with an additional 50% retaliatory tariff on China, which will take effect at midnight tonight. The new tariff—levied after Beijing responded to Trump’s initial tariff with a 34% retaliatory tariff of its own—means that as of tomorrow, Chinese goods will face crippling import duties of more than 104% in the United States. Various administration officials, including Trump, have indicated that the United States is currently fielding requests for trade negotiations from “many” countries, but National Economic Council Director Kevin Hassett said Tuesday that Trump had instructed his subordinates to prioritize discussions with “allies” such as Japan and South Korea over talks with China. Trump wrote on Truth Social Monday night that if Beijing did not drop its tariff—which it has not done—“all talks with China concerning their requested meetings with us will be terminated!” And The Wall Street Journal reported last week that the Trump administration had been stonewalling Chinese diplomats and officials since taking office in January.

→Quote of the Day:

The current trendline is catastrophic. The PRC [People’s Republic of China] is poised to dominate unfolding revolutions in electric vehicles and telecommunications; China has manufacturing capabilities that trounce those of G7 countries, and the economic depth to increase its military capacities while the U.S. defense industrial base declines. If these trends hold, the outcome is inevitable: capital will flee the other advanced countries for the PRC. This is a military risk for the present security order, a financial and trade risk to the international economic system, and also an existential risk for the hundreds of millions of workers in advanced countries who will find themselves in gig and service jobs that are insufficiently productive to support a first-world lifestyle.

That’s from a 2024 essay in American Affairs by the Federal Communications Commission’s Nathan Simington, “China Is Winning. Now What?”

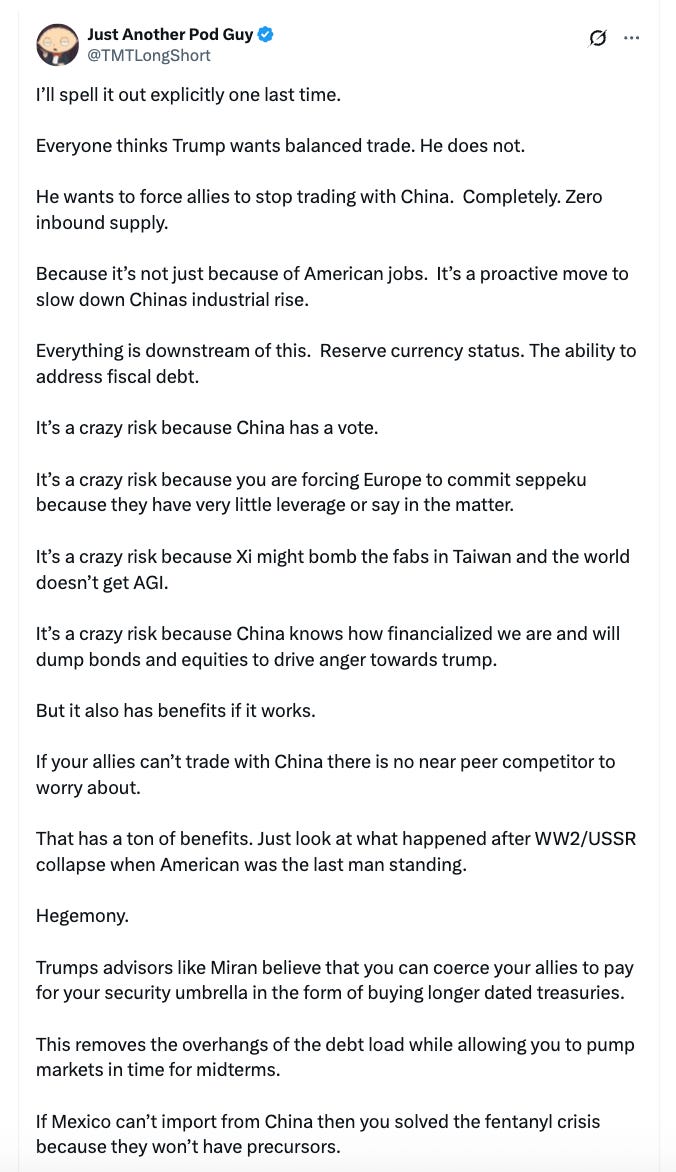

→A theory to consider, which rhymes with our own:

→One of the nice things about our new age of Transparency™ and Citizen Journalism™ is that we can see high-level policy discussions playing out in public, in real time. Consider this enlightening exchange between White House senior counselor Peter Navarro, one of the architects of Trump’s tariff policy, and Elon Musk. In a Monday appearance on CNBC, Navarro dismissed Musk’s criticisms of the tariffs by claiming that Musk was more of a car “assembler” than a “maker.” Musk disagreed:

→Shot, from the Feb. 20 edition of The Scroll:

Secretary of Defense Pete Hegseth has instructed Pentagon leaders to draw up plans to cut defense spending by 8% for each of the next five years, The Washington Post reports. Distributed Monday and reported on by the Post last night, Hegseth’s memo instructed military leaders to fund only what was needed for a “wartime tempo” while cutting “low-impact items” such as DEI programs and “climate change studies.” (The Pentagon’s budget is about $850 billion, so Hegseth is looking to cut roughly $68 billion in year one.)

→Chaser, from an article last night in Politico:

President Donald Trump and Defense Secretary Pete Hegseth pledged a first ever $1 trillion defense budget proposal on Monday, a record sum for the military.

But hey, $780 billion, more than $1 trillion—who’s keeping track?

→Just in time for a new round of Iran “diplomacy,” the Senate on Tuesday confirmed Elbridge Colby for the position of undersecretary of policy at the Department of Defense, the top policy position at the Pentagon. Colby passed on a largely party-line vote; despite rumors that many GOP senators were unhappy with his nomination, only one, Kentucky’s Mitch McConnell, ultimately defected. Colby also received the votes of three Democrats: Mark Warner of Virginia, Elissa Slotkin of Michigan, and Jack Reed of Rhode Island. For a chronicle of The Scroll’s own past tangles with Mr. Colby, you can read Lee Smith’s essay for Tablet here. And for a consideration of the role of the “realists” and “restrainers” in the broader MAGA ecosystem, read Mike Doran’s essay in today’s Back Pages.

SCROLL TIP LINE: Have a lead on a story or something going on in your workplace, school, congregation, or social scene that you want to tell us about? Send your tips, comments, questions, and suggestions to scroll@tabletmag.com.

The King’s Foils

Distrustful of a Republican foreign policy establishment that undermined him in his first term, Trump sourced a cohort of second-term staff from previously marginalized Libertarians and anti-interventionists. The problem? They don’t agree with him on policy.

by Michael Doran

When Donald Trump returned to office in January 2025, he moved fast. Within days, he had reinstated sweeping sanctions on Iran's oil exports, financial institutions, and entities linked to the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC).

On February 9, Benjamin Netanyahu became the first foreign leader to meet with Trump at the White House. The Israeli leader urged decisive action against Iran's nuclear program. Tehran, he argued, was weaker than it had been in years. Now was the time to break its back. Trump listened and nodded but didn't commit. According to U.S. and Israeli officials, he told Netanyahu he wanted to test diplomatic options first.

To further signal restraint, Trump sent a private letter to Iran's Ayatollah Khamenei proposing new negotiations. On Truth Social he posted, "Reports that the United States, working in conjunction with Israel, is going to blow Iran into smithereens ARE GREATLY EXAGGERATED. I would much prefer a Verified Nuclear Peace Agreement, which will let Iran peacefully grow and prosper."

But two weeks later, Trump revealed the limits of his inclination to bargain with Iran. On March 15, U.S. forces launched coordinated strikes on Houthi targets in Yemen after a series of attacks on commercial shipping in the Red Sea. Two days later, Trump posted, "Every shot fired by the Houthis will be looked upon, from this point forward, as being a shot fired from the weapons and leadership of IRAN. Iran will suffer the consequences, and those consequences will be dire."

National Security Advisor Mike Waltz appeared on Face the Nation on March 23 to explain the wider context of the attack on the only major Iranian proxy that had escaped significant harm from Israel: "Iran has to give up its program in a way that the entire world can see. They will not and cannot be allowed to have a nuclear weapons program. That includes weaponization and strategic missiles."

On Gaza, the contrast with Biden administration policy was even starker. Trump dropped the arms embargo Biden had imposed during his final months and green-lit Israeli operations in southern Gaza. He made no mention of a "day after" plan, no gestures toward the Palestinian Authority, no talk of a political horizon. Instead, he floated what he called a "Riviera" solution: The United States would take an "ownership position" in postwar Gaza, overseeing a reconstruction and development project that would begin after a major population transfer.

Whatever its feasibility, the plan made one thing clear: Trump had no intention of following the Obama-Biden playbook in the Middle East—not on Gaza, not on Iran, not on anything. These early actions reveal the core of Trump's foreign policy approach on the Middle East: a willingness to leverage American power while avoiding entanglement, oscillating between shows of force and diplomatic outreach—a strategic zigzag that confounds both allies and adversaries but consistently advances America's position.

Yet it is certainly possible to arrive at a very different apprehension of Trump's approach to foreign policy based on the statements of some of his most prominent supporters and advisers, especially if one spends a lot of time on social media. In the view of many who offer themselves up as speaking for Trump, or for his voter base, the true Donald Trump isn't a nationalist leader in the Teddy Roosevelt mode, who may speak softly but is by no means averse to using the big stick of American military and economic power. Rather, he is—or should be—a kind of cross between a 1930s right-wing isolationist and a 1960s antiwar protester. This highly visible version of Trumpism calls not for seeking global advantage by putting America's interest first, but for a unitary global policy of withdrawal and restraint, to avoid getting sucked into future wars, which, in its view, inevitably damage America to advance the interests of corrupt cliques of globalists.

This version of Trumpism calls itself "Restraintism." With respect to the Middle East, it advances four core propositions. First, the United States shares many strategic interests with Iran—interests that can, through deft American diplomacy, be realigned to mutual benefit. Second, Israel is the obstacle to this realignment, dragging the United States into needless and dangerous conflicts with Tehran. Third, given the increasing importance of competition with China, Washington should scale back its military commitments in the Middle East and pursue a thaw with Iran to help facilitate retrenchment. And fourth, the Palestinian-Israeli conflict is a strategic priority. It deserves much more attention from American leaders, who should offer the Palestinians greater support while forcing major concessions to them by Israel.

Restraintists present themselves as speakers of truth to power—voices that the legacy media and the corrupt establishment have long suppressed. They claim Restraintism is new, fresh, and popular. An expression of Trump's "America First" vision, it represents ordinary Americans who are rising against the "uniparty."

In fact, there is nothing new or uniquely Trumpian about this. Restraintism has flourished for decades within the foreign policy elite—inside the very uniparty it claims to oppose. In Progressive foreign policy circles, Restraintism reigns so supreme that, before now, some observers understood it only as a component of Progressive ideology. While it is that, it is also something more. For example, it is the default setting of Libertarians, like the Koch brothers and their aligned think tanks and networks.

How can it be on the right and left simultaneously? Restraintism is not so much a political ideology as a foreign policy persuasion. A permanent fixture in the American foreign policy debate, it resurfaces under different guises—sometimes as social justice, sometimes as free market Libertarianism, sometimes as populist revolt. It adapts its tone to the moment and to the setting, but its core claims remain intact. Some elites in both major political parties and in the career national security bureaucracy embrace its propositions, as do elements of the electorate. Kentucky Sen. Rand Paul and Vermont Sen. Bernie Sanders—despite coming from opposite ideological poles—are both leading representatives of the Restraintist persuasion.

The talking points of the Restraintists artfully mask the clash between the persuasion's core beliefs and the instincts of ordinary Americans. Restraintism combines easily with Marxism, Progressivism, and Libertarianism, with which it shares a common appeal: the allure of the one big idea, the promise of hidden, superior knowledge. For underemployed young men or professionals in the tech economy, it provides a ready-made worldview: sleek, contrarian, and anti-establishment.

In its harsher expressions, it offers cover for darker impulses. It has become a favored mask for those who rail against shadowy elites and, at times, unmistakably, "the Jews." According to the hardcore Restraintists, the mainstream press remains captive to "the neocons," shorthand for entrenched elites who, often Jewish, champion strong U.S. support for Israel to promote senseless global engagement. With an air of certainty and intellectual superiority, Restraintists advance pseudo-solutions to complex problems—solutions that, as we'll see, snap under pressure.

***

Just as Restraintism appealed to Progressives under Obama and Biden, it now appeals to a segment of the populist right—not so much as policy, but as posture. Trump shares some of their suspicions and some of their tone. He also shares some of their foreign policy prescriptions—but more so on Ukraine and NATO than on Israel and Iran.

Take Michael Dimino, Trump's deputy assistant secretary of defense for the Middle East. Before entering government, Dimino was part of a Washington network funded in part by the Charles Koch Foundation, which has long advocated reducing U.S. involvement in the Middle East. Before taking office, he said on a podcast, "There are no vital or existential U.S. interests in the Middle East." On the U.S. presence in Iraq and Syria, he added, "We're really there to counter Iran, and that's really at the behest of the Israelis and the Saudis."

But Dimino is not the movement's power center. Tucker Carlson, the conservative broadcaster and longtime Trump ally, has amplified Restraintist voices for years—and is arguably more influential than most officials with titles. The Washington rumor mill now names Vice President J.D. Vance, Donald Trump Jr., and Sergio Gor, director of the White House Office of Presidential Personnel, as fellow members of the Restraintist camp. Whatever the truth of those rumors, the movement has certainly gained proximity to power.

And a self-confident public voice. MAGA-aligned media now routinely host voices who echo the Restraintist view. One example: Economist Jeffrey Sachs recently told Carlson that Israel is dragging the United States into a war with Iran. "Netanyahu, I regard as one of the most delusional and dangerous people on the planet," Sachs said. "He has engaged the United States so far in six disastrous wars, and he's aiming to engage us in yet one more."

So why has Trump stacked his administration with Restraintists—people who sometimes have loony ideas that he doesn't follow? The answer is simple: He no longer trusts the traditional Republican foreign policy establishment, elements of which, in the first term, slow-walked his orders, leaked to the press, and quietly cheered his impeachment. The old guard is out, disqualified by its manifest public disloyalty and now stigmatized as "neocon." Whoever is on record as opposing "the neocons" is therefore in line for a promotion from the margins to the power centers of D.C.

In place of the disloyal Republican old guard, Trump has tapped Libertarians and anti-interventionists who, until recently, lived on the margins of the Republican foreign policy community. They lived in the kinds of think tanks funded by the Koch brothers (who, ironically, opposed Trump in 2016, 2020, and again in 2024) and by heavyweight Democratic donors such as George Soros and Pierre Omidyar, whose political strategies involve creating Republican cover for leftist policies. They are young, eager, unentrenched. They owe their positions to Trump—and their futures depend on his favor, which makes them (in theory, at least) potentially more loyal than their predecessors. Their scorn for conventional expertise mirrors Trump's instincts and flatters his base. They claim to speak for the common men and women who fought America's wars in the past quarter-century, and some of them have served in the military.

Yet their influence on Trump's Middle East policy remains limited. Trump listens to their views. He occasionally follows their tactical advice but never their strategic direction, and especially not when it comes to Iran and Israel.

To understand the limits of Restraintism's influence, it's useful to distinguish it clearly from the broader skepticism toward military intervention that swept the American public in the aftermath of the Iraq War. After years of costly and often unsuccessful operations, most American voters are wary of large-scale military deployments in the Middle East. "Let someone else fight over this blood-stained sand of the Middle East," President Trump declared in 2019, playing to the sentiment.

The wave of public skepticism gave Restraintists an edge in the foreign policy debate. But their core propositions still clash with mainstream American opinion—especially among Republicans, both traditional and MAGA. Americans may reject large-scale military deployments in the Middle East, but they understand that leaving the Middle East altogether and thereby handing control of the global energy markets to China is lunacy. They still support Israel, distrust Iran, and don't believe the United States can stand by while Tehran builds nuclear weapons—positions that Trump also holds.

The Signalgate episode revealed the split between Trump and the Restraintists. In March 2025, a senior Trump official mistakenly added a journalist to a Signal chat group for coordinating airstrikes against the Houthis. The group included Vice President Vance, Defense Secretary Pete Hegseth, National Security Advisor Waltz, and others. When the discussion turned to timing and escalation, Vance raised concerns. "I am not sure the president is aware how inconsistent this is with his message on Europe right now," he wrote. "There is a further risk that we see a moderate to severe spike in oil prices." He suggested delaying the operation for a month—but added, "I am willing to support the consensus of the team and keep these concerns to myself."

The consensus moved ahead. Defense Secretary Hegseth shared targeting details. And then came the line that settled the debate. "POTUS is good to go," wrote Homeland Security Advisor Stephen Miller. Vance's concerns had been registered—but overruled. The strikes went forward. On the Middle East, Restraintists whisper from the wings. Trump listens. Then he goes his own way.

Which brings us to the deeper point. Trump's foreign policy zigzags between Restraintists and hawks—not out of confusion, but by design. The zigzag reveals the strategy. Its purpose is leverage. He's executing the hybrid model he built in his first term: part Bush, part Obama; maximum pressure, minimal military footprint. The Houthi strikes are just the latest example. They didn't lock Trump into war; they gave him options. He can negotiate with Iran from a position of strength—or strike again, from that same position.

Unlike the commonly assumed chaos of Trump's decision-making, this oscillation between conflicting approaches serves a coherent strategy: It creates uncertainty for adversaries and flexibility for the United States and gives Trump multiple pathways to advance American interests. By deliberately pitting opposing viewpoints against each other in his administration, Trump maintains control over the final decision while extracting maximum value from each perspective. The public nature of the oscillation allows Trump to appeal to domestic political constituencies with widely divergent perspectives.

In the Obama and Biden administrations, Restraintism shaped Middle East policy directly. Senior officials, however, masked that fact. They devised clever slogans to hide their appeasement of Iran and their decision to distance the United States from Israel. In the Trump administration, Restraintism calls more attention to itself but does not yet wield the same degree of influence. To be sure, it has occupied a few prominent cars on the Trump train—where it is popping champagne, beating drums, and blowing horns—but it is not driving the locomotive. To understand why it isn't and why it won't, we have to scroll back and review its role in Washington over the past two decades.

Read the rest of this essay at Tablet: https://www.tabletmag.com/sections/israel-middle-east/articles/kings-foils-donald-trump-foreign-policy

Michael Doran superbly explains that regardless of the inner debates among Trump's appointees he alone determines policy-and what a welcome change it is from the failed policies of Obama Biden and Blinken policy of appeasing Iran and throwing Israel under the river

Maybe Trump did not get the latest message from Tehran?

Iranian paper repeats calls to 'shoot Trump in skull' Apr 6, 2025,

Iran’s ultra-hardline Kayhan newspaper, managed by a representative of the Supreme Leader, has repeated weekend calls to assassinate US President Donald Trump to avenge the 2020 killing of IRGC commander Qassem Soleimani.

On Sunday, the daily expressed support for what it described as revenge for the drone strike in Iraq, ordered by Trump during his first time in office, just one day after a piece had warned "a few bullets are going to be fired into that empty skull of his".

Feb 4, 2025 — President Donald Trump said Tuesday that he's given his advisers instructions to obliterate Iran if it assassinates him.