February 21, 2024: Is Affirmative Action Back?

Harvard faculty share antisemitic cartoon; J-Street’s “open door” to the State Department; 30-year high in food costs

The Big Story

The Supreme Court may have “ended” race-conscious admissions with its decision in Students for Fair Admissions (SFFA) v. Harvard last June, but the practice is likely to survive, if a Tuesday decision from the Supreme Court is any indication.

On Tuesday, the Supreme Court declined to hear a challenge to admissions practices at Thomas Jefferson High School for Science and Technology (TJ), a highly selective specialty public high school in Alexandria, Virginia. Like similar specialty schools in New York City, such as Bronx Science and Stuyvesant, TJ had long offered admissions based on a highly competitive, race-blind admissions process that relied heavily on standardized test scores. Eighth graders were invited to apply if they had at least a 3.0 GPA and had taken a class in algebra, at which point applicants were subject to four rounds of standardized tests and asked to submit teacher recommendations. Those who passed were then selected based on a holistic review. The result of this meritocratic process was a heavily Asian American student body.

Too Asian, as it turned out. In 2020, amid the country’s “racial reckoning,” TJ officials began to panic about the school’s racial demographics, with the school’s principal going so far as to send an email to the heavily Asian student body lamenting that the school did not “reflect the racial composition” of Fairfax County’s public schools. In December 2020, TJ adopted a new admissions process, which scrapped standardized tests in favor of a “holistic” process that distributed most slots to top students at each of the district’s public middle schools and allotted the rest based on a weighted review of grades, an essay, and “experience factors.” These included eligibility for reduced-price meals, status as an English-language learner, and attendance at a public middle school that had historically sent few students to TJ.

The result was as intended: The Asian American proportion of admissions dropped 19 points under the new system, from 73% to 54%, while the number of Black and Hispanic students roughly quadrupled. Parents challenged the new admissions policy in court, and in 2022, a federal district court ruled the policy unconstitutional, noting that it clearly had been formulated to reduce the Asian proportion of the school’s student body. Emails and text messages between TJ board members and other school officials, for instance, “demonstrated that the purpose of the Board’s admissions overhaul was to change the racial makeup [of] TJ to the detriment of Asian-Americans.” Last year, however, a divided Fourth Circuit Federal Court of Appeals reversed that decision, ruling that because Asians are still overrepresented at TJ relative to their overall share of the population, they cannot be disadvantaged by the policy—even though the new policy discriminated against all individual Asian American applicants by reducing their chances of admission.

By declining to hear the case, the Supreme Court is allowing that appeals court ruling to stand. In effect, it is saying that “racial balancing” is constitutional as long as it is done through race-neutral criteria—despite the Supreme Court seeming to rule against such “indirect” consideration of race in SFFA v. Harvard. As a precedent, moreover, the appeals court ruling would seem to permit discrimination against any group that performs better than its share of the population—Jews very much included. Justices Samuel Alito and Clarence Thomas, at least, appeared alive to this danger. A dissent to Tuesday’s decision written by Alito and joined by Thomas argued that the Fourth Circuit’s ruling “effectively licenses official actors to discriminate against any racial group with impunity as long as that group continues to perform at a higher rate than other groups.”

Alito and Thomas also warned that the Fourth Circuit’s decision could undermine the Supreme Court’s ruling in SFFA v. Harvard:

The Fourth Circuit’s reasoning is a virus that may spread if not promptly eliminated. Indeed, the First Circuit has already favorably cited the Fourth Circuit’s analysis to disparage the use of a before-and-after comparison in a similar equal protection challenge to a facially neutral admissions policy. … And TJ’s model itself has been trumpeted [by the dean of UC Berkeley’s Law School] to potential replicators as a blueprint for evading SFFA [v. Harvard].

We suspect that Alito and Thomas are correct, but that the apparent problem with the ruling—i.e., that it preserves exactly the sort of race-conscious admissions policies that the court appeared to ban in SFFA v. Harvard—is a feature, not a bug.

IN THE BACK PAGES: Israeli historian Benny Morris on the place of Gaza in the Israeli mind

The Rest

→Image of the Day:

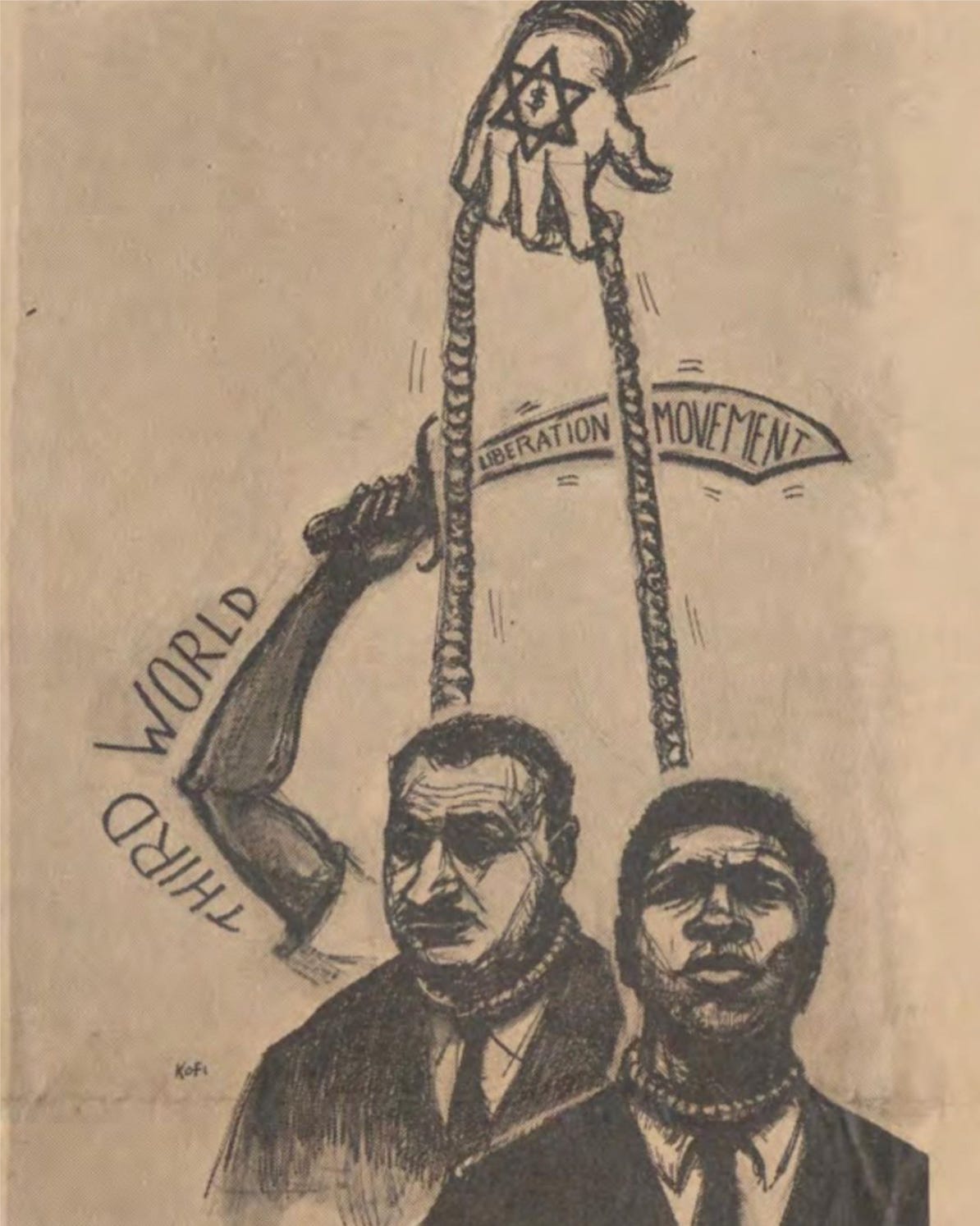

That’s a cartoon of a “Jewish” hand—note the Magen David with a dollar sign in the middle—holding boxer Muhammad Ali and former Egyptian president Gamal Abdel Nasser in nooses, which the arm of the “Third World” is cutting with a sword labeled “Liberation Movement.” We suppose the point is something like this: International Jewry (sorry, “Zionism”) is jointly exploiting Blacks in the United States and Arabs in the Middle East through its control of the financial system, and the only solution is Third World revolution.

The cartoon, which originally appeared in a 1967 newsletter from the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, reappeared in an infographic on African people’s “profound understanding of occupation and apartheid.” Initially posted to Instagram on Monday by the Harvard Undergraduate Palestine Solidarity Committee, it was then reposted by Harvard Faculty and Staff for Justice in Palestine (HFSJP), a “newly formed collective” affiliated with the boycott, divest, and sanction movement. Harvard announced Monday that it was opening an investigation into the “despicable” image, and HFSJP has apologized, sort of. “It has come to our attention that a post featuring antiquated cartoons which used offensive antisemitic tropes was linked to our account,” the group said on Monday. “We apologize for the hurt that these images have caused and do not condone them in any way.”

→The founder of J Street, the George Soros-funded NGO lobbying for a cease-fire in Gaza and conditions on U.S. aid to Israel, thanked senior State Department officials for providing him with an “open door” in June 2021 email correspondence, The Washington Free Beacon’s Adam Kredo reports. “Thanks for the open door,” J Street founder Jeremy Ben-Ami wrote to then Deputy Secretary of State Wendy Sherman, in an email that was forwarded to Undersecretary for Political Affairs Victoria Nuland and then chargé d’affaires in Jerusalem Michael Ratney, who now serves as U.S. ambassador to Saudi Arabia. The correspondence concerned a June 2021 Jerusalem Day demonstration by Jewish Israelis, which J Street was lobbying for the Israeli government to cancel. Publicly, the administration urged “calm” and “restraint” at the demonstration, but privately, the State Department echoed J Street and pushed for Netanyahu to cancel the parade, citing a need to reduce tensions following threats from Hamas. Netanyahu allowed the parade to go on, but rerouted it so that it would not pass through Jerusalem’s Muslim Quarter.

In addition to demonstrating the close cooperation between the Biden administration and left-wing NGOs in formulating policy, the correspondence offers a window into the White House’s playbook for dealing with Israel—its supposed ally—and Israel’s terrorist enemies, such as Hezbollah and Hamas. Rather than backing Israel against those group’s threats, the White House uses the threats as leverage to force Israeli concessions, always under the guise of “reducing tensions” in the region.

Read the rest here: https://freebeacon.com/israel/j-street-founder-had-open-door-to-top-biden-state-department-official-internal-emails-show/

→Quote of the Day:

We will continue to actively engage in the hard work of direct diplomacy on the ground until we reach a final solution.

That was U.S. Ambassador to the United Nations Linda Thomas-Greenfield, speaking yesterday after vetoing a U.N. Security Council resolution calling for an immediate cease-fire in Gaza. Washington’s preferred “final solution” to the Jewish question in Palestine appears to be to preserve Hamas in Gaza and then empower it through the creation of a Palestinian state under the control of Palestinian Authority Prime Minister Mohammad Shtayyeh, who on Sunday reiterated his desire to incorporate Hamas into the Palestine Liberation Organization. Asked about making common cause with a terrorist group that perpetrated mass murder and rape against Israeli civilians, Shtayyeh said, “One should not continue focusing on Oct. 7,” according to a report in The Times of Israel.

→Stat of the Day: 33 years

That’s how long it’s been since Americans have spent as much of their income on food as they do today, according to a Wednesday article in The Wall Street Journal. In 2022, the most recent year for which U.S. Department of Agriculture data is available, American consumers spent 11.3% of their disposable income on food; up from less than 10% for most of the 2000s and below 10.5% throughout the 2010s. The last time relative food prices were this high was 1991, when consumers, still dealing with the impact of the steep food price inflation of the 1970s, spent 11.4% of their disposable income on food. Since the data stops in 2022, the cost today may be even worse: Labor Department data shows that restaurant prices rose 5.1% between January 2023 and January 2024, while grocery prices rose 1.2%. And food prices seem likely to stay high. “If you look historically after periods of inflation, there’s really no period you could point to where [food] prices go back down,” Steve Cahillane, the CEO of Kellanova, told The Wall Street Journal. “They tend to be sticky.”

→Computer science professor Mauricio Karchmer, who quit MIT in December over the school’s response to campus antisemitism, has taken a job at Manhattan’s Yeshiva University. In a January article for The Free Press on his decision to leave his “dream job” at MIT, Karchmer wrote that he could “no longer deal with the pervasive antisemitism on MIT’s campus.” He will begin teaching two classes at Yeshiva this week: portfolio management and math for computer science.

Read Karchmer’s Free Press essay here:

→The Biden administration will forgive $1.2 billion in student loan debt for 150,000 borrowers, the White House announced Wednesday, providing details for a program unveiled in January. Americans enrolled in the administration’s Saving on a Valuable Education (SAVE) plan who borrowed less than $12,000 will see their balances erased after 10 years of payments. The administration has approved about $138 billion in student debt relief, but its most ambitious program, an executive order to erase $430 billion in student loan debt, was rejected by the Supreme Court in June 2023.

→Argentina saw its first monthly budget surplus in 12 years in January, the country’s Ministry of Economy announced last week. January was the first full month in office for President Javier Milei, Argentina’s Chabad-curious libertarian president, who has pursued an aggressive program of “shock therapy” for Argentina’s moribund and inflation-ridden economy, including dramatic spending cuts, the abolition of price controls, a 50% devaluation of the peso, and increased interest rates. The government announced a surplus of $589 million in January, its first monthly surplus since August 2012, but poverty and inflation also rose. Milei has promised an economic rebound within three months, and his economy minister announced on X last week that “the zero deficit is not negotiable.”

TODAY IN TABLET:

The Future of Lox, by Sonya Sanford

As supplies of salmon become less sustainable and prices less affordable, what are we supposed to put on our bagels?

SCROLL TIP LINE: Have a lead on a story or something going on in your workplace, school, congregation, or social scene that you want to tell us about? Send your tips, comments, questions, and suggestions to scroll@tabletmag.com.

Gaza in the Minds of Israelis

A new collection of essays, published just before October 7th, captures the complexity of the current war

By Benny Morris

On April 29, 1956, Ro’i Rothberg, the security officer of Nahal Oz—one of the kibbutzim attacked by Hamas terrorists on Oct. 7, 2023—was gunned down by Palestinian ambushers who had infiltrated Israel from the Gaza Strip. During the previous weeks, Rothberg had routinely chased off infiltrators who had come to reap the sorghum crop from the kibbutz’s fields. The ambush was the payback.

The following day the IDF chief of general staff, Moshe Dayan, delivered a memorable eulogy at the graveside. He said:

Yesterday, at dawn, Ro’i was murdered … Let us not, today, cast blame on the murderers. What can we say against their terrible hatred of us? For eight years now, they have sat in the refugee camps of Gaza, and have watched how, before their very eyes, we have turned their lands and villages, where they and their forefathers previously dwelled, into our home … How did we shut our eyes, and refuse to look squarely at our fate and see, in all its brutality, the destiny of our generation? Can we forget that this group of youngsters [i.e., Ro’i’s fellow kibbutzniks], sitting in Nahal-Oz, carries on its shoulders the heavy gates of Gaza? Beyond the furrow of the border surges a sea of hatred and revenge; revenge that looks towards the day when the calm will blunt our alertness … We are a generation of settlement [dor hitnahalut] and without the steel helmet and the gun’s muzzle we will not be able to plant a tree and build a house. Let us not fear to look squarely at the hatred that consumes and fills the lives of hundreds [of thousands] of Arabs who live around us … [We must be] ready and armed, tough and harsh—or else the sword shall fall from our hands and our lives will be cut short.

A few months after Rothberg’s murder, the Gaza Strip—along with the Sinai Peninsula—was conquered in the Sinai-Suez War of October-November 1956 by the IDF, led by Moshe Dayan.

In May 1948, during Israel’s War of Independence (or, in Arab parlance, the “Nakba,” meaning the catastrophe), Egypt had occupied the Gaza Strip, which was until then part of British Mandate-ruled Palestine. The Egyptians held onto it until November 1956 when it fell to the IDF. After four months of Israeli rule, the Strip returned once more to Egyptian control and remained Egyptian, with no thought of it becoming a self-governed territory, until it was conquered again by Israel in the 1967 Six-Day War.

Over the decades, the Strip has periodically been the springboard of attacks on Israel and the target of Israeli retaliation. Israel formally pulled out of the Strip in 2005, leaving it in the hands of the homegrown Islamist movement Hamas, which since then has periodically attacked Israeli settlements and troops with rockets, missiles, and mortars. This campaign culminated in the surprise Oct. 7 Hamas assault on southern Israel. The current IDF counteroffensive against Hamas is shaping up to be the third Israeli conquest and occupation of the Gaza Strip.

By the end of the 1948 war, some 700,000 Arabs had been uprooted from their homes in what had become the State of Israel, and thus they became refugees. Close to 200,000 of them ended up in the Gaza Strip. Most, like Ahmad Yassin, the founder of Hamas, originated in the nearby villages around the Strip that eventually became part of Israel. Today the Strip has a population of some 2.2-2.3 million, three-quarters of whom are descendants of the 1948 refugees, and a quarter of whom are the descendants of the area’s pre-1948 population.

Gaza has long loomed large in the minds of Israelis—a crucial capital of their mental maps.

In 2010 Israeli artist Tamir Zadok produced a nine-minute mockumentary called “The Gaza Canal” (te’alat ‘aza). Mixing maps, news and video clips, photographs, satellite imagery, and “interviews” with experts, the mockumentary depicted how in 2002 an Israeli American political-geographic project physically severed the Gaza Strip from Israel and Egypt by cutting a deep, 61-kilometer trench or canal along Gaza’s borders with Israel and Egypt. The operation eventually triggered an earthquake which, while devastating Gaza’s cities, effectively deepened the fissure and set the Strip adrift in the Mediterranean. A border that had been a battlefield for more than five decades, was transformed into an island of parks, smiling girls, high tech enterprises and joyous sun-tanned tourists.

Thus Yitzhak Rabin’s famous 1992 fantasy wish—“for my part, Gaza can sink in the sea” (which he immediately rolled back by adding “[unfortunately] it is not possible”)—was now magically transformed by Zadok into an ideal resolution of the Gaza problem beneficial to all: a battlefield transmogrified into a resort-cum-pleasure dome for local Arabs and international clientele. In the mockumentary the narrator declares: Don’t say “it can’t be done”—in Hebrew i efshar. But i efshar in Hebrew can also mean “island (i) [is] possible (efshar)”—“an island of commerce, industry … a green island … an ecological island … a symbol of health … change … an island of perfection.”

Sadly, Zadok’s utopia, like all utopias, was a fantasy and remains unrealized.

Gaza also figured large, metaphorically, in the rhetoric of the Palestinian national movement. Yasser Arafat, the head of the Palestinian national movement from the 1960s until his death in 2004, famously declared that those who doubt that the Palestinian aspiration for statehood will ever be realized “should go drink from the waters of Gaza’s sea.”

Now a new academic work, Gaza: Place and Image in the Israeli Landscape (Gama Publishers, 2023), edited by Omri Ben Yehuda and Dotan Halevy, which appeared in Israel just before the Oct. 7 assault, looks at the role of Gaza in the Israeli imagination more fully. An anthology of essays by Israelis and Arabs, it deals as much with metaphor and rhetorical devices as it does with history. In it, Amira Hass, a daughter of two Holocaust survivors and longtime columnist in Haaretz, devotes a long essay to Gaza’s refugee population. Hass knows her subject intimately—she lived in the Strip from 1993 to 1997 (and currently lives in the Arab town of Al-Bira in the West Bank). Her essay, “Both on the Fringes and at the Center: Gaza as the Palestinian Microcosm,” begins: “Whoever has not tasted Gaza’s local Sheikh Ajlin grapes has never tasted [good] grapes. Juicy, mildly sweet, soft on the palate.” But many of the Sheikh Ajlin vineyards “have been uprooted over the past twenty years in the [successive] offensives of destruction and revenge carried out by the IDF [in response to Palestinian rocketing and terrorism].”

Gaza, Hass points out, used to export wine in Byzantine times, when the Strip, with Gaza City at its center, was a crossroads of empires and peoples, where goods and ideas were liberally exchanged. “The historical accident generated by Israel”—Hass presumably means in 1948, 1967, and the virtual siege of Hamas-ruled Gaza since 2005—turned Gaza into an isolated enclave. “The abomination [sha’aruriya] lies in Israel’s success in imprisoning the Strip’s two million inhabitants … and compressing them into a corner, transforming [the Strip] into a huge concentration of beggars [mikbatz ‘anak shel mekabtzei nedavot].”

During the first decades of the post-1967 Israeli occupation, Gazans were relatively free to visit Israel (and the West Bank) and work in Israeli settlements, including in the border-hugging kibbutzim. But this freedom disappeared in the early 2000s as rocketing, terrorism, and counterterrorism became daily fare along the border.

As Hass points out, the isolation of Gaza over the decades has shaped a distinct identity and esprit de corps that today separates its inhabitants physically and psychologically from their cousins in Israel (the Israeli Arab minority) and also from Palestinians in the West Bank and East Jerusalem. No doubt the Gazan experience since the start of the IDF counteroffensive that began on Oct. 8—with most of the population turning into internal refugees inside the Strip’s devastated buildings and infrastructure—can only have deepened this separate and distinct identity. “Gaza became a mini-Palestine,” writes Hass of the years before Oct. 7, and it is no wonder that the leadership of the Palestinian armed factions—(the “resistance,” in Palestinian parlance) largely emerged from Gaza’s refugee camps.

Since 2005, as Dotan Halevy, one of the anthology’s editors puts it in the introduction, a generation has grown up in Gaza “that knows nothing of Israel” (and in Israel, a generation that “knows nothing of Gaza”). Unfortunately, that generation of Israelis is now getting to know Gaza too well. During the Oct. 7 assault, hundreds or even thousands of the Strip’s civilians streamed into southern Israel. They plundered and, alongside the Hamas fighters, murdered and raped—while their faces shone with profound joy.

In one of her contributions to the anthology, Sama Hassan, a Gazan writer and journalist voicing the anguish of Gazans, writes: “My friends in this enfeebled and tired and stubborn and proud land, Gaza is like a woman struggling with her drunk husband. He wakes up sober and clear-headed in the morning, but his disheveled hair and bloated eyes are a constant reminder that he will return to the bottle and to unleash mayhem when night falls.”

One of the volume’s most striking essays is “Daddy Works in Gaza,” by Yuval ‘Arab ‘Ivri, the son of Nissim ‘Arab ‘Ivri, an Israeli administrator who worked in Gaza between 1973 and 1983 during the second Israeli occupation. Yuval teaches in the Near East and Jewish Studies Department at Brandeis University. Nissim was in charge of employment in the Strip and Sinai. Looking through the family photo albums, the son, who was 9 when Nissim abandoned the home and family, notes that his father looks like his Arab colleagues and clients—dark-skinned with a prominent black moustache and an un-Israeli suit. The family apartment was bedecked with a collection of swords Nissim had acquired in Gaza. Nissim was at one with his Arab work environment—he was a native Arabic speaker, born in Basra, Iraq, in 1938.

Many of Israel’s post-1967 occupation officials, in Gaza as in the West Bank, were of Middle Eastern origin, hired because of their fluency in the language and culture of the occupied. “His Arabness [‘arviyuto] had changed from a hump [hatoteret] that needed to be hidden and erased to an ‘expertise’ or ‘merchandise’ that opened up new vocational opportunities [and an avenue to] social mobility,” writes the son.

But, at the same time, the new job did not provide internal tranquility. “My father’s sense of shame from his Arabness, which was dominant during my childhood and youth, was, over time, replaced by another type of shame, of an almost opposite [order] … a sense of embarrassment because of his work in the civil [meaning military] administration in Gaza and from his involvement in the service of the Israeli occupation.” Yuval notes that the upper echelons of the Israeli occupation bureaucracy in the Palestinian territories were manned by Ashkenazi Jews.

His work seemingly allowed Nissim to reconnect with the language of his childhood, with his roots. But Yuval notes that the Arabic used by the Israeli administrators who helped oversee Gaza’s occupation was not the Arabic spoken in Iraq’s streets but a hybrid Arabic-Hebrew construct, studded with words pertinent to an occupation—an Arabic of “permits, and prohibitions,” of “regulations and guidelines,” a language that had passed through a mechanism of Israeli “securitization” (bit’honizatziya).

In a throwaway line, Yuval reveals that one of his uncles, David (‘Arab) ‘Ivri, was among the founders of Kibbutz Be’eri, another of the kibbutzim ravaged by Hamas on Oct. 7.

Uri Cohen, who teaches Hebrew and Italian literature at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, in his essay “Gaza Has Come: The White City and the Twin City,” argues that Gaza is “the ghost of the country, of Palestine.” By which he means that Gaza is in effect a mirror image of “little Israel, a crowded and closed entity of refugees. Israel and Gaza contain each other like Babushka dolls: a narrow strip [of land], unconscionably crowded, with tightly shut borders, with hostile neighbors, whose name carries [the weight of] the past.”

In his essay “The Refugee as an Enemy,” Omri Ben Yehuda, the anthology’s co-editor, notes that Gaza’s refugees are not “run-of-the-mill refugees … who seek shelter but flatly demand [the territory of] Israel itself, [that is] those who were dispossessed from [Israel] desire to inherit [or dispossess] those who dispossessed them.” This highlights the left-liberal Israelis’ abiding dilemma: The Palestinian national movement’s unwillingness to reach a two-state compromise, and its ultimate goal of possessing all of Palestine for itself, mirrors the right-wing Israelis’ desire to possess, unshared, the whole Land of Israel.

There are no amount of Supreme Court decisons that could ever get our left clerisy to abandon their sacred mission to socially (re)engineer based on race, most especially in the upscale precincts of America where a commitment to "Diversity" now works as both a class marker and moral credential.

If the Civil Rights Act (maybe) created a second Constitution (at least according to Chris Caldwell), it absolutely gave birth to a new religious movement where the pain of minorities became sacralized and a new post-Marxist vanguard class marched through our institutions determined to transform America based on the principles of "Social Justice". Unless we're planning a military occupation of every admissions and employment office in America, or some radical form of de-funding or a countrywide de-Wokeification campaign, we will just have to fight every battle one at a time.

I wasn't quite sure if Benny Morriss's essay had a definite thesis. He often seems determined to not be nailed down to a position--unfortunately, that gives his writing the feel of a high school book report.