In Out of the Fog, historical detective Brian Berger digs through newspaper columns, clippings, and other clues to bring readers the fascinating, scandalous, and forgotten tales of the past. In this installment … we tour the Brooklyn of Lou Reed’s childhood and rediscover the forgotten inspirations of the Velvet Underground great.

Lou Reed never hid his Brooklyn roots, but he did surround them with so much myth, irony, and half truth that even his admirers found it difficult to know his true origins in the borough.

There were reasons for this, not least Reed’s often contentious relationship with the press, and a preference for expressing himself in character. But it is possible now, almost a decade after Reed’s death, to see how the details of his early days in Brooklyn made his artistic devotion to the borough all the more striking.

**

Lewis Allen Reed was born in Beth-El Hospital (Brookdale Hospital today), in Brownsville on Monday, March 2, 1942. The front page of that afternoon’s Brooklyn Eagle was dominated by World War II, and local headlines like “Cop, 3 Others Shot in Wave of Holdups” and “Judge’s Wife Saves Slayer From Chair” betray any myths of a borough idyll.

Reed’s grandparents were Yiddish-speaking Eastern European immigrants—paternal side Polish, maternal side Russian—who made new lives in Brooklyn. If we cannot know them personally, we may yet know their kind from Jewish American folklore and the stories of Bernard Malamud. Reed’s father, Sidney Rabinowitz (1913-2005), was an accountant from the largely Jewish and Italian neighborhood of Borough Park.

Reed’s mother, Toby Futterman (b. 1920-2013), was from what was then the city’s largest Jewish community, Brownsville, renowned for Pitkin Avenue, boisterous left-wing politics, and gangsterism. In 1939, Futterman—who’d left high school early to help support her family—earned fame as Queen of the Stenographers, a beauty contest covered in, among other publications, the Communist newspaper Daily Worker.

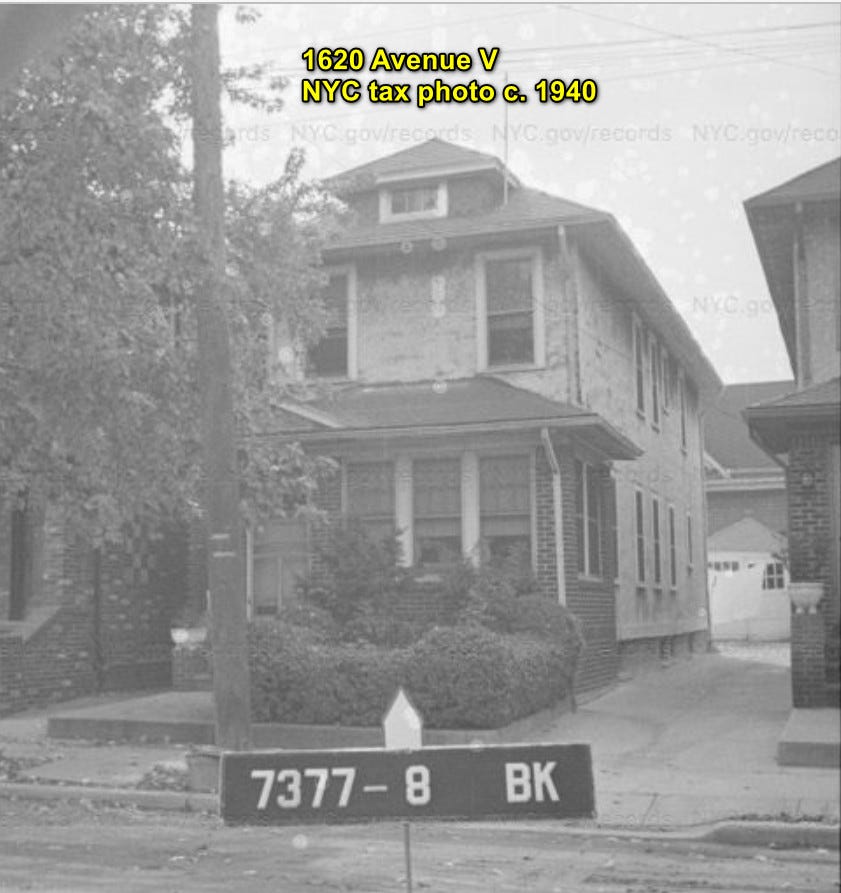

Sidney and Toby met shortly afterward and would marry. In an effort to elude corporate antisemitism, Rabinowitz legally changed his last name, and thus that of his family, to Reed. With baby Lewis, the family’s first home—as discovered in a Brooklyn telephone directory—was 1620 Avenue V, near East 17th Street, in Sheepshead Bay.

A few years later, the Reeds had a daughter named Merrill and moved north, to 1477 East 27th Street, near Kings Highway, in Midwood.

Reed would attend school just four blocks away, at P.S. 197 on Kings Highway. Though he’d recall these years as ones of fear and violence, such claims run contrary to the neighborhood’s placid Jewish middle-class reputation. Certainly, there was plenty of casual violence those days in a Brooklyn still a half century away from mass gentrification. Still, of the borough’s many rough neighborhoods, Reed’s wasn’t one of them.

In 1952, Reed’s father took a position as treasurer of Cellu-Craft, a manufacturer of packaging materials, and the family moved about 25 miles east, buying a home in Freeport, Long Island.

For Lou Reed, Brooklyn boy, the transition was difficult but not impossible, and his childhood on the island began as one of comfortable suburban normality: sports, girls, music—he even had a bar mitzvah, though his parents were largely non-religious. Reed also had a furtive, more troubled side, and during his first year attending New York University’s campus in the Bronx, he suffered a nervous breakdown, one perhaps related to his experimentation with drugs and homosexuality. However it would be diagnosed and treated today, the answer then, the Reed family was assured, was ECT, electroconvulsive therapy. While its impact would be lifelong and traumatic, Reed did improve.

Next Reed attended Syracuse University, where he had friends and girlfriends and a successful band, L.A. and the Eldorados. Perhaps most significantly, it was there that Reed developed a transformative relationship with a professor, the well-known writer Delmore Schwartz, author of the classic In Dreams Begin Responsibilities and himself a Brooklyn Jew with fraught family pains. Reed graduated with honors in English in 1964—the same year Hubert Selby Jr.’s landmark avant-naturalist novel Last Exit to Brooklyn was published. Shocking for its time, Selby’s account of violence, depravity, and casual amorality established a literary style—raw, street-level, brutal yet empathetic—to which Reed, who revered the novel, would aspire.

While Reed’s career with his band, The Velvet Underground, was commonly associated with Manhattan, especially its downtown scene, there was one notable exception. In October 1969, the Velvets recorded Reed’s lighthearted “Coney Island Steeplechase,” including the lines:

Would you like to go on the Coney Island Steeple

Go and have a good time

We’ll take the subway right down to Kings Highway

Though it remained unreleased until 1986, the song showed that Brooklyn remained in Reed’s heart.

**

Brooklyn came to the forefront in Reed’s 1976 album, Coney Island Baby. Adopting the voice of a radio DJ in the title track, Reed intones:

I’d like to dedicate this one to Lou and Rachel and all the kids at P.S. 192

Man, I’d swear I’d give the whole thing up for you.

Rachel—originally known as Richard—was Reed’s transgender, male-to-female lover and companion.

On a searing live version of the song from Reed’s 1978 album, Take No Prisoners, he declares—added to a long version of “Sweet Jane” and jokingly referencing his acolyte, Patti Smith—“Fuck Radio Ethiopia, I’m Radio Brooklyn!”

The love for Brooklyn showed itself again in his underrated, often happy 1995 album, Set The Twilight Reeling. Its opening track, “Egg Cream,” is about just that.

Becky’s on Kings Highway was the egg cream of choice

And if you don’t believe me, go ask any of the boys.

Reed elaborates:

The only good thing I have to say about P.S. 92

Was the egg cream served at Becky’s, it was a fearsome brew

Wait—what?! P.S. 92 in Prospect-Lefferts Gardens—like the P.S. 192 of “Coney Island Baby”—is a school Reed never attended, but what the hell: The poetic license of the kid from P.S. 197 is good anywhere.

As for Becky’s, this mystery still abides. A couple blocks east of P.S. 197, across Ocean Avenue, Kings Highway turns from residential to archetypical neighborhood Brooklyn: a dense, low-rise jumble of ground-floor shops with apartments above. In 1950, it was mostly Jewish, including delis, candy stores, and restaurants—any of which could have served an amazing egg cream.

Despite intensive research, however, Becky’s—if that was the formal, not colloquial, name of his egg cream purveyor (that is, if Lou didn’t just make it up!)—remains unfound.