March 29, 2024: Hit the North

Biden, Obama, Colbert raise $25 million; Harvard applications down; U.S. covertly supports UNRWA

The Big Story

The Israeli Air Force carried out major airstrikes in northern Syria, near Aleppo, before dawn on Friday. Unconfirmed media reports suggest that at least 38 and possibly more than 40 people were killed, among them Syrian soldiers and five Hezbollah operatives. Video of one of the strikes shared on social media on Friday shows the IAF hitting what appears to be an ammunition depot, likely linked to Hezbollah and the Iranian Revolutionary Guard Corps, both of which operate freely in Syria:

Indeed, Israel appears to be stepping up the tempo of its operations in the north. The IDF confirmed it had killed the deputy commander of Hezbollah’s rocket unit in an airstrike in Lebanon, also on Friday. Defense Minister Yoav Gallant, meanwhile, announced on Friday that he had directed the IDF to “expand the campaign in the north.” In a statement, Gallant said:

We are shifting from repelling to actively pursuing Hezbollah. Wherever they are hiding we will reach them, including more distant places like Damascus and beyond. We will increase the rate of attacks and expand our operations—that’s what I conveyed this week in Washington to Secretary of Defense Austin, to Special Envoy Amos Hochstein, and others—and that’s what I instructed the IDF at Northern Command.

Frankly, the IDF probably would have liked to go into Lebanon in October last year, but given that the Biden administration’s first act after Oct. 7 was to caution Israel not to risk “regional war” by striking Hezbollah, we suppose the Israelis decided to try to limit their conflicts with the Americans as much as possible. Not that they’re being repaid much for their cooperation. As the Huffington Post’s diplomatic correspondent posted on Thursday:

This “top Lebanon watcher” whose “assessments” are supposedly being confirmed by a “U.S. official” is, of course, Amal Saad, a Lebanese Axis of Resistance shill so deranged that she was once denounced by Max Blumenthal for her “malevolent propaganda” on behalf of Syria’s Assad regime. Then again, the U.S. line on Lebanon—that Israel wants to use it as a “pretext to draw the U.S. into a wider war” (as Saad states in the part of her post cut off in the screenshot)—is the same as Hezbollah’s, so who knows what’s real anymore.

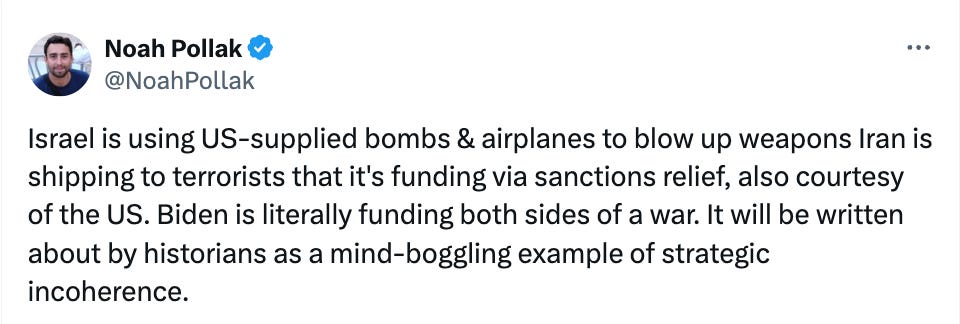

Meanwhile, Noah Pollak nails the dynamic on X: namely, that Washington doesn’t want its “ally” bombing its other allies:

IN THE BACK PAGES: For Easter weekend, Thomas Doherty revisits ‘Ben-Hur,’ Hollywood’s towering Christo-Zionist epic

The Rest

→Joe Biden raised more than $25 million at a Thursday fundraiser in New York City with former presidents Barack Obama and Bill Clinton, hosted by Stephen Colbert, for which tickets ranged from $225 to $500,000. A report in The New York Times from earlier this week, moreover, noted that Obama is making “regular calls” to Biden and to White House Chief of Staff Jeff Zients to “strategize and relay advice.” We take that as an indication that Obama, the first ex-president since Woodrow Wilson to stay in Washington, D.C., after his presidency, wants to reassure Times readers that, yes, you idiots, of course I’m still running the country.

→But the fundraiser didn’t go off without an appearance from anti-Israel hecklers—including one man caught on camera berating a female attendee as a “murderous kike”—which brings us to our Post of the Day:

→Applications to Harvard and Brown declined this year, even as other elite colleges posted record admissions numbers. According to a report in The New York Times, applications to both Harvard and Brown fell about 5% this year, while applications to MIT and Columbia rose 5% and applications to Yale and Dartmouth rose by about 10%. The Times suggested, amusingly, that Harvard’s reputation may have been dented by … drum roll … the Supreme Court decision striking down affirmative action last year, the resignation of the university’s first Black president (Claudine Gay), and “students losing job offers for speaking up about Israel-Palestine.” In other words—Harvard isn’t woke and antisemitic enough! Although, hey, given what Gen Z is learning on TikTok, the Times may well be right.

→Quote of the Day:

This week, Salma Hamamy, president of the main pro-Palestinian student group at the University of Michigan, shared (and then deleted) a social-media message stating, “Until my last breath, I will utter death to every single individual who supports the Zionist state. Death and more. Death and worse.” (The University sent an email denouncing the message.)

While she may be an undergrad, Hamamy is hardly anonymous. She was one of four undergraduates to receive the University of Michigan’s Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. Spirit Award honoring students “who best exemplify the leadership and extraordinary vision of the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.” The Michigan Daily endorsed her campaign for student-council president. State, national, and international newspapers have quoted her warning Biden to change course and citing her as an example of the kind of progressive Democrats have to placate.

Last month, the New York Times jointly profiled her and a pro-Israel activist in a story presenting both as searching for common humanity.

That’s from Jonathan Chait’s latest column in New York magazine, making the quite reasonable point that the left can claim either that the student and activist is so important that Biden must listen to it or that it is so unimportant that journalists must not report on it—but not both.

→The Palestinian Authority announced the formation of a new cabinet on Thursday, under new Prime Minister Mohammad Mustafa, who will also serve as foreign minister. As a report in The Times of Israel notes, “None of the incoming ministers is a well-known figure,” which means they have no independent base of support outside of their patron, Mahmoud Abbas, and the rest of the senior PA/Fatah leadership. Mustafa has vowed to form a “technocratic government and create an independent trust fund to help rebuild Gaza.” On Friday, a group of “Israeli policy experts” from the Israel Policy Forum (read: members of the Herodian class who want Israel to remain an American satrapy) released a report recommending that Israel integrate the PA into the Gaza humanitarian effort to “give Ramallah accountability over the process” and “smooth its transition to eventually return to governing the enclave after the war,” per another report in The Times of Israel.

→On March 20, we reported that Saudi Arabia had announced $40 million in funding for UNRWA on the same day that U.S. Secretary of State Antony Blinken landed in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, and the day after Congress struck a deal barring U.S. funding for the agency until 2025. Today, The Washington Free Beacon’s Adam Kredo confirmed that wasn’t a mere coincidence. A State Department spokesperson told the Free Beacon that “we will be looking to other donors to continue providing critical funding to UNRWA as long as our funding remains paused.” Canada, Japan, France, Sweden, and Finland also have all recently announced that they are restoring their funding for UNRWA. The State Department declined to “publicly discuss content of our diplomatic conversations” surrounding UNRWA, but The Globe and Mail reported earlier this week that U.S. Ambassador to the United Nations Linda Thomas-Greenfield had “implored” Canada to keep funding UNRWA.

→Cryptocurrency wunderkind and Biden megadonor Sam Bankman-Fried was sentenced to 25 years in prison on Thursday for defrauding customers of his cryptocurrency exchange, FTX, which collapsed in November 2022. “SBF” had, among other things, used customer funds to prop up losses from a hedge fund, Alameda Research, run by his lover Caroline Ellison; funneled millions in the form of cash and Caribbean real estate to his parents, Stanford law professors Joseph Bankman and Barbara Fried; lied to regulators and government authorities; doctored business records to mislead investors; and ultimately lost more than $8 billion worth of depositor funds. He also, according to Judge Lewis Kaplan, obstructed justice and attempted to tamper with witnesses in mounting his defense, which factored into the sentencing. Until the end, though, SBF and his parents appeared to believe he hadn’t really done anything wrong, with Bankman and Fried writing a presentencing letter to the judge stressing their son’s “great nobility” and “depth of understanding and critical thinking”—as evidenced by his veganism and studies of the utilitarian philosopher Derek Parfit.

We’ll leave you with this mini essay from Robert Sterling:

On that note, enjoy your weekend.

TODAY IN TABLET:

Free Evan Gershkovich, by Bernard-Henri Lévy

By taking an American journalist hostage, Putin’s Russia announces its transformation into a full-blown terrorist state

SCROLL TIP LINE: Have a lead on a story or something going on in your workplace, school, congregation, or social scene that you want to tell us about? Send your tips, comments, questions, and suggestions to scroll@tabletmag.com.

Today’s Back Pages is an excerpt. Read the full version here.

The Miracle of ‘Ben-Hur,’ Hollywood’s Tastiest Christo-Zionist Epic

A story of unabashed Jewish pride and human depth that honors Christians and Jews alike, with a sly gay subplot courtesy of Gore Vidal

By Thomas Doherty

In the American Masters documentary Directed by William Wyler (1986), Charlton Heston tells the kind of story that gives actors night terrors. He is starring in the title role of MGM’s $15 million epic Ben-Hur. The dailies are coming back and director William Wyler is not happy. Heston can take criticism, he can work with a director, he appreciates guidance. What do you need? he asks.

“Better,” snaps Wyler.

Heston got better of course. Ben-Hur went on to win 11 Academy Awards, save MGM from insolvency, and imprint itself on the popular imagination. A successful roadshow reissue in 1969 solidified its status and television made it a yearly ritual beginning on Feb. 14, 1971, when CBS devoted a long Sunday night to the first telecast, with a pan-and-scanned version interrupted, lamented one critic, by an “unmerciful number of commercials.” (No matter: It drew an estimated 86 million viewers, more than any film yet broadcast on television.) In a line-up of bloated and overlong biblical epics (see Demetrius and the Gladiators [1954], The Ten Commandments [1956], and The Bible: In the Beginning [1966]), it remains a compulsively watchable exception in a genre that has dated badly. New York Times film critic Bosley Crowther, usually the scourge of grandiose Hollywood religiosity, called Ben-Hur “by far the most stirring and respectable of the Bible-fiction pictures ever made ... grippingly conveyed in some of the most forceful personal conflicts ever played in costume on a giant screen.” (Spartacus [1960] is not a biblical epic.)

Before its definitive rendering, however, Ben-Hur had already passed through a series of hugely popular iterations on what were not yet called media platforms: a bestselling book, a hit stage play, a one-reel short from the dawn of cinema, and an equally spectacular feature film from the silent era. Each version reflected its distinct cultural milieu and media moment, with the two major film versions serving as convenient bookends for the rise and fall of classical Hollywood cinema. The first version in 1925 launched Hollywood into its vaunted "golden age," when the machine works of the studio system proved that the art of cinema could depict most any landscape conjured by a writer’s imagination; the second arrived when the studio system was on a downward slide but not yet out for the count.

The origin story of Ben-Hur begins not in Hollywood or Rome but in Santa Fe, in the territory of New Mexico, where territorial Governor General Lew Wallace—lawyer, Civil War hero, and diplomat—wanted to add novelist to his list of accomplishments. In 1876, he began work on the one he would be remembered for, Ben-Hur: A Tale of the Christ, published in 1880. Teleporting readers back to Judea and Rome at the time of Christ, the book caught the retro zeitgeist of a nation transformed by industrialization (the essential skill set in the novel, horsemanship, was already something of a throwback). Within a decade, the novel had sold 250,000 copies. Ben-Hur has been called “the most influential Christian book written in the nineteenth century”—that’s wrong, the correct answer is Uncle Tom’s Cabin—but it ranks a close second.

The book’s subtitle is a bit of a cover story: Ben-Hur is not a Christian conversion narrative, but an American tale of class fluidity and identity-shifting. In Jerusalem circa 27 CE where the Jewish people suffer under the yoke of Roman occupation, the Jewish prince Judah Ben-Hur lives with his widowed mother, Amrah, and beloved sister Tirzah, their business affairs overseen by their dedicated steward Simonides and his comely daughter Esther. In boyhood, Ben-Hur had bonded with the son of the Roman governor, Messala, who has returned to the backwater garrison town as the Roman tribune. When a loose tile from the house of Hur beans the new Roman governor, Messala condemns his former friend to the death-in-life of a galley slave. Amrah and Tirzah are locked away in the bowels of a dungeon and forgotten. At dramatically parceled-out beats, the life of Ben-Hur intersects with the life of Christ.

After years of upper body exercise chained to the oars of a Roman trireme, Ben-Hur is fit, muscular, and burning with the vengeful rage that has kept him alive. When the Roman armada is attacked by pirates, he saves the life of the Roman commander Quintus Arrius, who adopts him as his heir. In Rome, Ben-Hur becomes the most famous charioteer in the empire, but he has not forgotten his roots, his family, or the imperative to pay back Messala.

Ben-Hur leaves the life of a sports celebrity in Rome to return to Judea, where he is reunited with the faithful Simonides and, after being briefly distracted by the hot Egyptian temptress Iras, embraces Esther as his true love. At the Super Bowl of chariot races held in the Circus Maximus in Antioch, Ben-Hur exacts vengeance against Messala, whom he leaves in his dust trampled underfoot. Ben-Hur has one more race to finish, though: to find Amrah and Tirzah, now lepers who will be cured by divine intervention.

In its time, Wallace’s “intermingling of so many chapters of fiction with the sacred history” was considered a near-blasphemous appropriation of the Gospels, but the balance in tone between reverence and revenge placated the religious while satisfying the bloodthirsty. Wallace could assume a normative Christianity in his readership, but he also forged a sympathetic identification with his flinty Jewish hero—a fierce Zionist years before Theodor Herzl convened the first World Zionist Congress in 1897.

Knowing a sure-fire hit with a pre-sold title, theatrical impresarios approached Wallace for the stage rights, but he refused to sell the property until assured, first of all, that the figure of Christ would not be depicted on stage; and second, that the stagecraft would do justice to the two great action set pieces in the novel—the naval battle and the chariot race. The firm of Klaw and Erlinger, veterans in orchestrating elaborate stage productions, persuaded Wallace of their sincerity and mechanical competence; they got the contract. William Young, a playwright experienced in telescoping the action of novels for the stage, compressed the action into six acts and 15 scenes.

On Nov. 25, 1889, Ben-Hur debuted as a play at the Broadway Theater in New York. Featuring a cast of hundreds, full orchestra, choir, and a marvel of stagecraft engineering, the show was mounted on a scale no theatrical production had heretofore approached. The depiction of the naval battle was merely impressive (waving drapes as the ocean); the staging of the chariot race was astonishing. Two full-sized chariots were locked in place on stage as two teams of horses galloped on treadmills in front of them. The wheels of the chariots whirred; clouds of dust blew in from offstage. “The most thrilling stage picture ever shown within the four walls of a playhouse,” gasped a critic who watched from the wings, expecting to be trampled at any moment. The audience, he said, “was at first stunned and then torn into a perfect paroxysm of cheers.” Christ was easier to render: His presence was suggested by a shaft of light. For the next 30 years, roadshow productions of Ben-Hur were mounted continuously across the U.S. and overseas in venues sturdy enough to support the special effects. “No other dramatic work has been seen by so many persons—hundreds of thousands witnessing the wonderful spectacle,” Billboard later reported.

In 1907 the Kalem Company, a pioneering motion picture production outfit, released the first film version, Ben Hur, a one-reel, 14-minute costume drama composed of “sixteen magnificent scenes with illustrative titles.” Brazenly advertised as “adapted from General Lew Wallace’s famous book,” the film elides the Christianity to mesmerize moviegoers with period pageantry. The sets and painted backdrops were borrowed from Henry J. Pain’s Fire Works Company, an outfit renowned for staging pyrotechnic shows drawn from the explosive annals of history (“Last Days of Pompeii,” “The Siege of Sevastopol”); the costumes were rented from the Metropolitan Opera. All in all, not a bad show for five cents. The film ripped off everything but the hyphen from the Wallace book, but in the wildcat days of early cinema, motion picture rights to a book or stage property were in a zone of uncertainty copyright-wise.

Not for long. General Wallace’s son Henry and the producers of the stage version sued Kalem for copyright infringement. Kalem argued that their Ben Hur was “merely a series of photographs” and, besides, the film was good advertising for the book and play. In 1911, the U.S. Supreme Court disagreed and issued a landmark decision holding that a book or stage property could not be made into a movie without permission from the copyright holder. Kalem was ordered to pay $25,000 and cease distribution. Novelists and playwrights rejoiced at the lucrative new revenue stream.

***

By the next decade, the art and technology of moviemaking had advanced exponentially. The emerging studio infrastructure—and the examples of maestros like D.W. Griffith and Cecil B. DeMille—meant that the great set pieces in Ben-Hur would no longer be constrained by the floorboards of the proscenium stage or a single camera bolted to the floor. In 1921, producer Sam Goldwyn conscientiously secured the rights to Ben-Hur and cut a mutually profitable deal with the copyright holders. By the time the cameras got rolling on the project, Sam Goldwyn Pictures had merged with Louis B. Mayer Pictures and Loews-Metro to become MGM.

Filmed on location in Italy, the first major film version of Ben-Hur was a notorious runaway production and money pit that served forever after as a cautionary tale that kept the major studios close to the backlot. The silent film historian Kevin Brownlow, who chronicled the devil’s-candy-like production travails in his history of the silent film era, The Parade’s Gone By ..., called it “a heroic fiasco.”

Rudolph Valentino, the original matinee idol, was considered perfect for the role of Ben-Hur, but Famous Players Lasky owned his contract. A relative unknown—George Walsh, brother of director Raoul Walsh—was initially cast, only to be replaced mid-production by Mexican American actor Ramon Novarro, plucked from the silent era’s roster of Latin lovers. The burly Francis X. Bushman sank his teeth into the role of the villainous Messala. The diminutive ingenue May McAvoy played Esther (she would also play the love interest of another famous screen Jew, Al Jolson, in The Jazz Singer [1927]).

Cecil B. DeMille, of course, was mentioned as a possible director, but the job went to a relatively untested Englishman named Charles Brabin. Above him in the pecking order was screenwriter June Mathis, who adapted the Wallace novel. Mathis was a serious power broker in Hollywood, credited with discovering Valentino and grooming his persona with her adaptations of The Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse (1921) and Blood and Sand (1922). In September 1924, cast, crew, and cameras abandoned the relative serenity of California and went on location in Italy.

Brabin and Mathis soon proved overwhelmed by the scale of the enterprise: wrangling thousands of non-English speaking extras and constructing nearly life-size replicas of Roman triremes, the Jaffa Gate for the Jerusalem set, and the Circus Maximus for the chariot race. They were shaken down by fascist dictator and self-styled Caesar Benito Mussolini and delayed by lackadaisical Italian workmen who were reluctant to finish a job that would end their ride on the Hollywood gravy train.

With the production stalled for weeks on end, the cast shopped and toured. Novarro visited the Vatican and received the blessings of Pope Pius XI, which may or may not have contributed to his survival from a near lethal chariot pile-up. Besides millions of 1920s dollars wasted (the total price tag would ultimately be put at $4 million), the location shoot in Italy cost the lives of a stuntman charioteer and three galley slave extras who jumped in panic off a Roman trireme and drowned (or at least they never returned to the costume department to retrieve their street clothes). An estimated 100 horses were euthanized. “If it limped, it was shot,” recalled Bushman.

Hemorrhaging money, MGM cashiered Brabin and Mathis and dispatched director Fred Niblo to take the reins. Niblo was experienced with large-scale costume dramas, having worked with Douglas Fairbanks Jr. and the inevitable Valentino.

In January 1925, Irving Thalberg, MGM’s hands-on head of production, finally pulled the plug and called the company back to the real land of bread and circuses. The centerpiece chariot race still needed to be filmed, so a second replica of the Circus Maximus was built outside the MGM plant in Culver City. Twelve chariots drawn by four horses raced around the enormous arena, the stands packed with 3,500 costumed extras. To make sure the mob behaved, plainclothes LA cops—clad in togas over their uniforms—were planted among the extras. Forty-two cameras were placed strategically around the arena to catch the action.

The filming of the chariot race was “my most harrowing experience,” Niblo recalled. “I lived sleepless nights dreaming of possible catastrophe.” There was one heart-stopping moment: Six chariots piled up, but both human and equine life emerged unscathed. (The crash was left in the final film.) Novarro and Bushman actually drove their chariots, with Bushman becoming quite proficient—you can see Niblo favoring him in the medium shots, which are not backscreen projection. Bushman later boasted, probably correctly, that he had done more chariot racing than any man alive.

On Dec. 30, 1925, Ben-Hur was rolled out with a gala premiere at the 1,000-seat George M. Cohan theater. Besides the usual swells and stars, the opening night crowd included a procession of “bishops, priests, and ministers representing all the denominations in the metropolitan district of New York City,” including the Rev. Dr. Stephen S. Wise, president of the American Jewish Congress and, like Judah Ben-Hur, a staunch Zionist. Civilians paid a top price of $2.20 for tickets (about $40 today).

Enthralled by the massive sets, color tinting, and throngs of costumed extras, audiences applauded throughout the film. During the chariot race, they cheered as if they were in the coliseum. When the house lights went up, director Niblo was greeted with an ovation worthy of an emperor. “It is the industry’s crowning achievement,” wrote Martin J. Quigley, editor of Exhibitor’s Herald. “The production of Ben-Hur will continue for years to be the greatest ambassador the industry has ever had.” Yet not all critics gave the film a thumbs up. According to Kevin Brownlow, Mussolini was furious when he saw that Messala, whom he thought was the hero, was defeated by Ben-Hur. He banned the film as “Christian propaganda” which “must not be tolerated in the present age of revolutionary enlightenment."

Read the rest here: https://www.tabletmag.com/sections/arts-letters/articles/miracle-ben-hur

There is no "strategic incoherence" here at all.

The people who control Biden need to put the Middle East on the backburner (on a very low simmer) until they can drag his moldy corpse across the finish line in November.

There is no greater cause here and the idea of appealing to any principles is preposterous: the owners of the Dem Party would ship their daughters to Hamas Finishing School if it could guarantee their victory over the Orange Beast.

They don't care how much rubble is created in Israel or in America, they only care about ruling over the rubble.

Robert Sterling's comment sets forth the intellectual and moral bankruptcy of the world view of SBF's parents and many who inhabit that stratosphere. where laws and regulations are made for others to obey but not themselves