The Big Story

What is going on at the Department of Defense?

On Sunday, The New York Times reported that Secretary of Defense Pete Hegseth had shared details of mid-March airstrikes on the Houthis in yet another Signal group chat, this one featuring his brother and his personal lawyer, who work for the Pentagon and the Navy Judge Advocate General’s Corps, and his wife, Jennifer, a former Fox producer with no formal government position. (The Wall Street Journal previously reported that Hegseth had brought Jennifer to “two meetings with foreign military counterparts where sensitive information was discussed.”) According to the Times report, Hegseth shared “information about the Yemen strikes” in the second chat, which featured several of his top aides, around the same time that he shared operational details of the strikes to the “principals committee” Signal chat described in two March articles in The Atlantic.

A Pentagon spokesman denied that any classified information was shared in this second chat, and accused the Times of relying on the word of “disgruntled former employees”—an accusation repeated by Hegseth in a conversation with reporters at a White House Easter event. “What a big surprise that a few leakers get fired and suddenly a bunch of hit pieces come out from the same media that peddled the Russia hoax,” Hegseth said.

For his part, Hegseth’s boss, President Donald J. Trump, dismissed the reports as “fake news,” telling reporters that “Pete’s doing a great job” and “everybody is very happy with him.”

Not everybody, exactly. Last week, we noted the suspensions of Hegseth’s senior adviser Dan Caldwell—a Koch network veteran and advocate of rapprochement with Iran—and deputy chief of staff, Darin Selnick, as part of a March 21 leak investigation ordered by Hegseth’s chief of staff, Joe Kasper. On Friday, Hegseth fired Caldwell, Selnick, and a third aide, Colin Carroll; on the same day, Politico reported that Kasper—who allegedly had a “personality clash” with the fired advisers—would be leaving his chief of staff role for a different job in the Pentagon. On Sunday, Politico magazine published an op-ed by a fourth former Pentagon staffer, John Ullyot, who defended the fired aides as the victims of a smear campaign and urged Trump to fire Hegseth, who was presiding over a “full-blown meltdown” at the Pentagon.

We can’t pretend to have inside knowledge as to why Caldwell and the others were fired, but we can make a few observations. For instance, last Wednesday, amid suspensions and firings at the Pentagon, The New York Times published a bombshell report, sourced to “administration officials,” that Trump had “waved off” a planned Israeli attack on Iran’s nuclear sites, motivated in part by the arguments of White House Chief of Staff Susie Wiles, Director of National Intelligence Tulsi Gabbard, Vice President J.D. Vance, and Hegseth. The article included extensive details about Israeli operational planning for a potential strike, including a scenario in which Israeli commandos, supported by U.S. and Israeli airstrikes, would rappel into Iran’s nuclear facilities, and a scenario in which the U.S. and Israeli air forces would first bomb Iran’s remaining air defenses before targeting its nuclear sites. One obvious purpose of leaking such details would be to tip off the Iranians and force Israeli military planners back to the drawing board. Indeed, Israeli officials told Israel Hayom that while the operational details in the report were “inaccurate,” the story had been planted by “officials in the U.S. administration seeking to block any possibility of military action against Iran.”

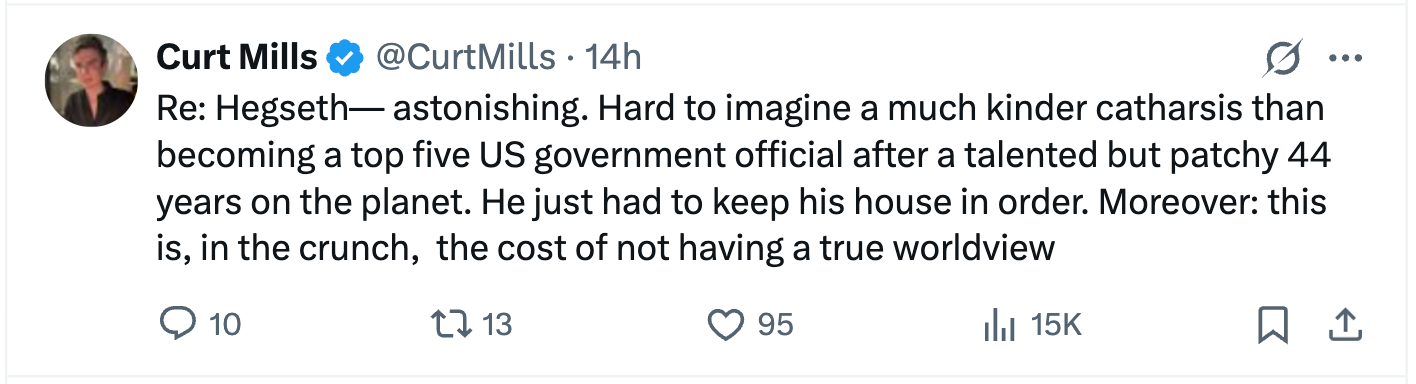

Following the publication of the Times report, allies of Caldwell—most of them orbiting around the sun of Tucker Carlson, who praised Caldwell as a “wonderful person” and “man of genuine integrity” in a February interview with Curt Mills of The American Conservative—rushed to connect the dots between the “purge” at the DOD and the thwarted Israeli attack:

Except the Times story said nothing about “Hegseth’s advisors” and depicted Hegseth as a rather minor player in the internal administration debate over whether or not to support an Israeli strike. So how could “Hegseth’s advisors” have prevented World War III? Well, as Saagar Enjeti pointed out in a separate post, someone leaked the “Pentagon’s own estimates” about the consequences of a potential strike on Iran’s nuclear sites to Carlson all the way back in March, as Carlson himself explained in an X post:

Note the timing—Carlson posted that message on March 17, four days before Kasper launched his internal investigation into “unauthorized disclosures.” And only days after Caldwell’s suspension and firing, the Times came out with its story about Hegseth’s disclosures to a second Signal chat. Outside of the recent reporting, none of the information from that chat has become public, and according to the Times, the only people in the chat were Hegseth’s wife and “about a dozen other people from his personal and professional inner circle,” among them Caldwell and Selnick. We’re going to take a wild guess and say it wasn’t Hegseth’s wife leaking to the Times.

Now, despite loose talk from the likes of Charlie Kirk about a “neocon” campaign to oust Hegseth, it’s the pro-Iran faction that suddenly appears to have soured on the secretary of defense:

In its frustration, the pro-Iran camp on the right is again making common cause with the anti-American left. In our March coverage of Signalgate, we observed the cozy relationship between Mills, an ally of Carlson and self-described proponent of “America First” foreign policy, and Drop Site News, a left-wing offshoot of The Intercept, which has traditionally been aligned with the Obama faction of the U.S. national security state and the foreign policy interests of Qatar. Drop Site cofounder Ryan Grim, as we’ve noted here on several occasions, is not only a rabidly anti-Trump socialist but also a regular font of Axis of Resistance messaging in his Israel and Middle East coverage. Curiously, despite his hostility to Trump and Trump’s foreign policy, Grim regularly receives leaks from sources in and around the Trump administration, all of which have the same basic gist: that “neocons” and “war hawks,” often associated with Mike Waltz’s National Security Council, are waging an internal battle against officials, like Caldwell, who oppose a “war with Iran.”

And whaddya know—on Monday, fresh off the latest round of infighting at the Pentagon, Grim had a new scoop, co-authored with his Breaking Points cohost Enjeti: that Merav Ceren, the director for Israel and Iran at the NSC, “formerly worked for the Israeli Ministry of Defense.” This is, strictly speaking, false, though it is based on an inaccurate description of Ceren’s work history taken from the website of the Foundation for Defense of Democracies. Ceren, an American Jew, did a postcollege policy fellowship with the Begin Center, in which role she was posted to Israel’s Coordinator for Government Activities in the Territories, housed under the MOD; she was never a “member” of the MOD or an MOD “official,” as the story alleges. Still, the story leans heavily into the idea that Ceren is an agent of a foreign power. Grim and Enjeti write:

It’s rare for a foreign country to be able to pitch American policymakers on a joint war effort and look across the table to see a former member of their own Ministry of Defense working for the Americans. As Trump debates his tariff policy, for instance, there are no high-level officials who previously worked for the Chinese Communist Party present.

So, the communists and isolationists agree: Jew warmongers loyal to a foreign country are purging patriots from the American government in an attempt to subvert Trump’s foreign policy and drive the United States to war with Iran. And who else agrees? Well, Qatari state-funded media; the Council on American-Islamic Relations; alumni of the Iranian regime’s U.S. lobbying arm, the National Iranian American Council; the journal of the Koch-Soros think tank the Quincy Institute; and Russian state media, all of which quickly amplified the “scoop” about Ceren. And if you can’t trust Doha, a front for the Muslim Brotherhood, NIAC, and George Soros to tell you what America First foreign policy is, who can you trust?

Which brings us back to what Lee Smith wrote for Tablet in March, which is that we are not witnessing an “internal fight” within MAGA, because there is no MAGA beyond Trump. Instead, Smith wrote, “What we’re seeing … is an external faction trying to attach itself to MAGA in order to strangle Trump’s America First foreign policy.” With that faction now openly attacking the administration and making common cause with its enemies to undermine the administration, the only question is how much longer Trump can put up with it.

—Park MacDougald

IN THE BACK PAGES: Gadi Taub on why the global right loves Hungary

The Rest

→Pope Francis died of a stroke on Monday at the Vatican at the age of 88. The first Latin American pope in history, as well as the first Jesuit, Francis, born Jorge Mario Bergoglio in Buenos Aires, was elected in 2013, following the resignation of the archconservative Benedict XVI. A progressive of a sort, he put a heavy emphasis on the socialistic elements of the Catholic Church’s traditional social teaching, speaking frequently of economic inequality, climate change, the alleged rapaciousness of capitalism and, more recently, his opposition both to Israel’s war in Gaza and to the Trump administration’s immigration policy. At the same time, he disappointed theological liberalizers who hoped he would reverse the church’s teachings on homosexuality and the ordination of women, even as he sought to crack down on expressions of traditionalist Catholicism, like the Latin Mass. To his credit, however, Francis, who had been gravely ill with complications from pneumonia for weeks, spent his last full day on Earth attending to the diplomatic and spiritual duties of his office; yesterday, on Easter Sunday, he met with U.S. Vice President J.D. Vance and greeted the Easter crowds in St. Peter’s Square.

For a balanced Catholic perspective on Francis’ legacy, read Matthew Walther’s essay in The Atlantic: https://www.theatlantic.com/ideas/archive/2025/04/pope-francis-legacy-church/681814/

And for a critical examination of Francis’ more recent statements on Israel, read Dr. Adam Gregerman’s essay in Tablet here: https://www.tabletmag.com/sections/israel-middle-east/articles/unfulfilled-promise-pope-francis-israel

SCROLL TIP LINE: Have a lead on a story or something going on in your workplace, school, congregation, or social scene that you want to tell us about? Send your tips, comments, questions, and suggestions to scroll@tabletmag.com.

Why the Right Is Drawn to Hungary

How the struggle between undemocratic liberalism and ‘illiberal democracy’ came to define Western politics

by Gadi Taub

Earlier this month, Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu had a high-profile meeting with his Hungarian counterpart, Viktor Orbán, in Budapest. Argentina's libertarian president, Javier Milei, has called Orbán his "comrade in this fight for the ideas of freedom," and Italy's Giorgia Meloni is Orbán’s "Christian sister." Last year, Donald Trump hosted the Hungarian leader three times at Mar-a-Lago. How did this one country in Europe become a beacon for right-wing ideas—and leaders—around the world?

Once upon a time, Hungary was the poster child of “regime change”—the peaceful transition from communism to democracy. The process was indeed peaceful. But was it really such a change? The transition was managed by the communist ancien régime, and its goal was to preserve power for its elite while pretending to strive for national consensus. The communists recast their image by manipulating the historical record, beginning with the uprising of 1956.

Everything important in Hungarian political life, it seems, goes back one way or another to that year, when the popular rebellion against the brutal dictatorship erected by the Stalinist boss of the Hungarian Communist Party, Mátyás Rákosi (born Rosenfeld), was ruthlessly suppressed by Soviet arms. The failed revolution would become ground zero for the competing narratives of the different political camps. Even Hungary’s transition to democracy in 1989 turned out to be about 1956.

The communists had attempted to impose an interpretation of the 1956 uprising as the eruption of counterrevolutionary forces. For their nationalist opponents, then and today, the rebellion was proof positive that Hungarian nationalism and democratic freedom were one and the same––the two faces of self-determination. Communism, being at once totalitarian and internationalist, was therefore a negation of both. This view of the 1956 revolution would later inform Hungarian suspicions towards liberal and progressive internationalism as well. That is, toward globalism and the European Union.

What followed the suppression of the 1956 Hungarian uprising was the long spell of the Kádár regime, often referred to as "goulash communism." János Kádár inherited a Soviet-occupied Hungary and was by no means soft in snuffing out whatever hopes Hungarians had for national liberation. But over the course of his 32-year tenure as general secretary of the Hungarian Socialist Workers' Party, oppression became less ruthless, and more attention was paid to raising the standard of living for ordinary Hungarians. The price was a mounting national debt, which would not have been sustainable had the Soviets not propped up the Hungarian economy. When Kádár left office in 1988, Perestroika was well underway in the USSR, and it was clear that Hungarian communism too would need to reform or die—or both.

It was in that year that the famous roundtable talks were born. They began as a forum for the leaders of the still-illegal opposition to talk among themselves. The following year, the communist regime, by now too exhausted to suppress the opposition, joined the roundtable, transforming it into the locus of negotiations over regime change. The communists found ways to expand their presence around the table by using various front organizations, such as the controlled labor unions, which supposedly represented real workers' interests. But no trick could disguise the fact that change was inevitable. The only questions were what shape that change would take, and who would guide it.

By means of the roundtable talks, the much-celebrated bloodless "regime change" was born. But behind the contrived facade of "national reconciliation," the communists set out first to ensure they would not be held accountable for the regime's crimes and then to make sure their own people would stay in key positions under the new system. Reconciliation actually meant exoneration, and for that reason, revising the narrative about 1956 was key.

The new narrative was somewhere in the middle, between the old communist version of 1956 as "counterrevolutionary" subversion and the national democratic ideal. The former communists "restructured the memory of the rebellion as a progressive struggle for an abstract notion of freedom devoid of the national character—in which they, the 'reformed communists' were the visionary leaders," says Levente Benkő, former Hungarian ambassador to Israel. This new version was dramatized in the belated funeral given to Imre Nagy. Nagy, the communist reformer and martyred prime minister of the 1956 uprising, was executed by the Kádár regime in 1958 for his role in the uprising, and his name was erased from the history books. He was buried in an unmarked grave, which remained under surveillance. Anyone attempting a pilgrimage to the grave was arrested.

Now, to legitimize “reconciliation,” former communists repented by switching retroactively to the other side of the 1956 barricades. Nagy received a hero's service in Budapest's Heroes' Square on June 16, 1989, the 31st anniversary of his execution—a gesture that was carefully calculated and stage-managed to accentuate the theme of "reconciliation." But this dramatization of repentance was also a form of self-exoneration. "From among the many martyrs of 1956," says Ambassador Benkő, "they chose a communist," thus turning 1956 from a national uprising against communism to a mainly internal struggle between hardline communists and communist reformers.” This suggested that there were bad communists and good communists, and that they—the regime-changers—were the latter kind. In effect, the communists were pardoning themselves in order to declare a clean slate.

The secret service of the one-party Hungarian state assessed the situation in 1989 as follows:

It has already been suggested to the population that the funerals on June 16 [Nagy's and those of other martyrs] must be regarded as a day of reconciliation and consensus … Now we can do more than ever to make sure that the democratic transition to the rule of law takes place peacefully, under the guidance of the MSZMP (the Hungarian Socialist Workers' Party).

Totalitarian habits die hard. The MSZMP was not ready to relinquish censorship, for example, but was conscious of the need to be less obvious about it. Miklós Vásárhelyi, former press secretary under Nagy's government, and the personal representative of George Soros in the Hungarian Academy of Sciences, helped with collecting the ceremonial speeches for advance screening. He got hold of all of them save one. And that was the one that crashed the reconciliation party.

"The majority of those who rose to speak," wrote journalist Bálint Ablonczy, "talked about the importance of reconciliation and stayed clear of disparaging the Soviet Union." But one speaker, a 26-year-old student who managed to keep his speech out of Vásárhelyi's hands, refused to play ball. The video of his speech is available online. The young man read it from a sheet of paper he held with both hands. His longish hair was slightly disheveled, but he wore a closely trimmed, manicured beard, a high-collared, starched white shirt, and a well-tailored black jacket. He had a ribbon on his lapel, which is hard to identify on the grainy video. Some sources say it was a Hungarian tricolor ribbon, with the red, white, and green of the Hungarian flag, and others maintain it was a black ribbon of mourning for the 1956 victims. The name of that young man was Viktor Orbán.

“If we believe in our own strength," the young Orbán said, "we will be able to end the communist dictatorship. If we are determined enough, we will be able to coerce the ruling party to submit to free elections. If we refuse to lose sight of the ideals of ’56, we will be able to elect a government for ourselves that will quickly move to talks about the urgent withdrawal of Russian troops. If we have the guts to will all of this, then, and only then, we shall fulfill the destiny of our revolution.” By "revolution" he meant the uprising of 1956.

This is the only speech anyone remembers from that event. Nine years later, at the tender age of 35, that young man would become the prime minister of Hungary.

Orbán’s move took considerable courage. After all, Soviet troops were still occupying Hungary at the time, and the communist dictatorship still held power. The young Orbán surely knew he was destroying the message of "reconciliation" that Hungary's rulers tried to impose using Nagy's funeral. But Orbán, who sat on the roundtable talks, was unable to disrupt their larger design, the plan to control "regime change" in order to perpetuate their power––a plan that had apparently been long in the making. The sons and daughters of the old communist guard had been pampered for some time, and part of the good life included education in Western universities. They were a more sober, worldly technocratic elite, and they knew that the fall of communism was inevitable. They were therefore out to ensure they would lose as little power as possible when the fall came.

***

Hungary, wrote historian Mária Schmidt, was "the only former Communist country which didn't opt for reprivatization—that is, where property was not returned to the original owners. Therefore, in the beginning, the only ones who could become capitalists were the former Communists." They were best situated, says Miklós Szánthó, director general of the Center for Fundamental Rights, "to transform their political capital into economic and cultural capital. They reached a tacit, unwritten agreement with Western investors to leave the staff and much of the management of privatized industries in place. Thus, the same people who ran state-owned banks, agricultural corporations, energy companies, media outlets, and so forth stayed on to operate them under new, private––mostly foreign––ownership.”

This trend also ensured continuity in the state bureaucracy. After all, the state had to continue functioning after the transition, and there were no new cadres to replace existing staff. Communist technocrats emphasized their indispensable administrative know-how while shedding their former commitment to Marxist ideology and downplaying their complicity in the old dictatorial regime. They were reincarnated as unbiased professionals.

The same happened in academia. New faculty could not be found overnight, so it was easier for the old to simply shift their formal allegiances. Under communism, universities and institutes with Marxist-sounding names—the Institute of Political History, the Karl Marx University of Economic Sciences, the Financial Research Institute, and so on—conferred a veneer of objectivity on ideological indoctrination. It would be a while before new institutes could take their place.

Continued control of the media was crucial. When the first freely elected government took office in 1990, the single public television channel decided not to broadcast its swearing-in ceremony in parliament. Instead it aired the European soccer competition. The new government was a conservative coalition led by Jozsef Antall, the leader of the Hungarian Democratic Forum Party (MDF), and the former communists who ran the channel were not about to give it even a single day of grace.

Another important milestone of the communist-controlled process of regime change was in the realm of law. Hungary adopted a temporary constitution and appointed a constitutional court before the first free elections were held in March 1990. The move was designed to ensure that "reconciliation," rather than accountability for communist crimes, would prevail. The new constitution was the old communist constitution of 1949, stripped of clauses that decreed a centrally planned economy and a leading role for the Communist Party.

According to Mária Schmidt, the move "to put the newly-established Constitutional Court in place before the free elections" was designed to secure, by judicial means, "the immunity of party leaders from prosecution." When the democratically elected new parliament, upon the initiative of conservative MPs, enacted a law in 1991 designed to punish those complicit in the worst of communist crimes, those that are defined as crimes against humanity (among them crimes perpetrated against the rebels of 1956) the Constitutional Court struck it down.

Finally, the Communist Party itself was reemerging in politics. The MSZMP, which controlled the state under communism, dropped the word Workers' and metamorphosed into the Hungarian Socialist Party (MSZP). In 1994, a mere four years after the "regime change,” the former communists were back in power. The socialist Gyula Horn became prime minister, leading an anti-nationalist coalition with the liberals of the Alliance of Free Democrats. They were warmly welcomed by the European Union. Internationalists of both shades were able to hold Hungarian patriotism in check.

The pendulum swung back to the nationalist side four years later in 1998. This time it was Viktor Orbán’s party, Fidesz, not the MDF, that led the coalition. But the shift was short-lived. After four years in power, Orbán's right-wing coalition lost once more to the socialists and their liberal allies. But the reason for Orbán's 2002 defeat, he came to realize, was not the rejection of his policies. Rather, it was the choke hold of former communists on so many extra-governmental centers of power that restricted his ability to govern, and, crucially, gave him constant negative press coverage. "Between 1998 and 2002 we were in government," Orbán would later say, "but not in power."

Orbán was therefore uniquely situated to understand the extra-electoral forces that can undermine democratic politics. True, Hungary's circumstances were unique to postcommunist central Europe—it had to fight the lingering legacy of communism from within, and then the internationalist pressure of the European Union from without. But the political operation of the mechanisms that threaten to neuter electoral politics is essentially the same in other places, including the United States and Israel.

What Orbán learned from being thrown off the electoral carousel was that it is not enough to win elections if the left controls the main institutions of state and society. Politicians can come and go through the revolving door of ballot boxes, and it would matter little, as real power would remain outside their grasp, and they would not be able to carry out the plans they were elected to realize. Orbán therefore made it his mission to level the playing field so that conservatives, too, would have a real chance to hold power and enact their agendas when elected by the people.

***

Orbán returned to power in 2010, determined to change the social and cultural context of politics in Hungary. "Having been defeated because most of the institutions of society, privatized industry and media in particular, were in postcommunist hands, as he thought, he determined that Fidesz would have to build up its own institutions," wrote John O'Sullivan, president of the Danube Institute, in the introduction to a book he edited in 2015, titled The Second Term of Viktor Orban: Beyond Prejudice and Enthusiasm. Fidesz would need to build "think tanks, media, universities, [and] civic bodies" so as to give the party "something like equality in the political struggle."

The effort began at the grassroots level with the “Civic Circles”—groups that were set up to mobilize communities and widen the party's support based on the assumption that a great many Hungarians were conservative, traditional, Christian, and patriotic.

The media was a major arena in the effort to level the playing field. As a heritage of communism, the left controlled about 80 to 90 percent of Hungary’s media market throughout the ’90s and early 2000s. It also controlled the public media. After his defeat in 2002, Orbán floated the idea of a second public television station, so that the right, just like the left, would have a channel supporting its views. Péter Medgyessy, the socialist prime minister who succeeded Orbán, rejected the idea offhandedly. "Whoever needs their TV [station] should buy one," he remarked snidely.

Orbán took that advice to heart. He went on to encourage conservative business people to invest in media outlets. The Center for Fundamental Rights’ Miklós Szánthó estimates that currently the share of the media market is about 55 percent for the left and 45 percent for the right.

When Fidesz won in a landslide in the 2010 parliamentary elections, achieving the two-thirds majority required to replace the temporary constitution with a new and permanent one, it wasted no time drafting it. The new constitution, which came into force in 2012, is called The Fundamental Law. The super majority also allowed the party to dominate the appointment of judges to the Constitutional Court and the Curia—the higher court of appeals—adding conservative judges to a bench previously stacked with judges with internationalist sympathies of both the socialist and the liberal progressive stripes.

The leftist opposition—and the media in the West—screamed fascism and accused Orbán of harboring authoritarian aspirations. But the truth is that the new constitution, though overtly conservative in some aspects—especially as it pertains to family values—was nothing like the "illiberal" reactionary document some pundits in the West have proclaimed it to be. Nor was the court neutered by the far right. Contrary to the wild allegations of its detractors, the court, under the new constitution, still has the power to strike down legislation and is not shy about using it. When it does, the government yields.

The left's near-total monopoly on universities, however, was harder to break. The Fidesz party supports Mathias Corvinus Collegium, an educational institution that offers assistance to talented conservative students. Orbán also forced George Soros’ Central European University to relocate to Vienna in 2018, in part because it subverted his immigration policy. That same year, his government also withdrew accreditation and funding from gender studies programs, claiming these were ideological rather than academic. But these measures fall far short of correcting the strong leftist bend of the universities.

As a result, think tanks have become crucial in the effort to diversify politics––by working upstream from them. In this field, Hungarian conservatives have proven original and innovative, such that Budapest has become a mecca for conservatives the world over. "History loves irony," wrote Szánthó in an introductory note to Shea L. Bradley-Farrell's Last Warning to the West: Hungary's Triumph Over Communism and the Woke Agenda. "And there is no small measure of it in an American truth-seeker coming to the Old World in hopes of finding solutions to a crisis in the United States."

The Center for Fundamental Rights, says Szánthó, its director general, "was founded in 2013 by a group of us young lawyers who were concerned about the way Hungary was discussed in the Western press. Every time the Orbán coalition advanced a piece of legislation, there was a screaming headline in The New York Times the next day proclaiming another victory for fascism. At first we thought, We're lawyers. We know our stuff, so we'll explain it to them and show them they are misunderstanding the issues. But we were naïve. No one wanted to listen to reason. So we realized this is politics, not law, and we began to think and act politically.” The center’s activities and its elegant residence on the Buda side of Budapest are financed by the Lajos Batthyány Foundation, which is affiliated with the Fidesz Party and makes no secret of this relationship.

One of the center’s flagship projects is CPAC Hungary, a yearly international event that brings together conservatives from many countries for the explicit purpose of creating an international conservative movement. "Many thought," Szánthó tells me, "that in contrast to progressive globalists and liberals, who share a clearly global vision, conservatives cannot unite, since they believe in preserving the particular heritage and tradition of the culture to which they belong. Our conservative views are therefore said to be what divides us. But this is not true, since conservatives share an opposition to a common globalist foe in the guise of the woke agenda. There is therefore much that they now share, and they can unite in mutual support in these cultural wars."

The center has also initiated an annual International Pro-Israel Summit in Budapest, inaugurated on a date that turned out to be symbolic: Oct. 9, 2023. I was scheduled to attend it but had to cancel my participation two days prior. On the morning of Oct. 7, as I was checking in my luggage at Ben Gurion Airport en route to Budapest, a journalist friend called to tell me things were much worse than we had heard up to that point, and that I’d better not go. I turned around and headed back home.

dotted-rule

Dr. Mária Schmidt is the director general of the Foundation for Research on Central and Eastern European History and Society, which supports the Institute of the 20th Century and the Institute of the 21st Century. The former focuses on the study of 20th-century dictatorships and the processes of regime change in former communist countries, while the second explores national sovereignty, democracy, market economy, and Christian culture. But the most conspicuous institution that the foundation supports is the House of Terror Museum, located on 60 Andrássy Avenue in the building that served during WWII as the headquarters of the Arrow Cross Party—the Hungarian version of Nazis that ruled briefly from 1944 to 1945. Under the communists, the building was converted to the headquarters of the secret police, the AVH.

Schmidt's office is inside the building, and from her perch amid the permanent exhibition, remarked one of my interlocutors, she controls Hungary’s national narrative. All school children in Hungary are required by their curriculum to attend the museum. And they all get Schmidt's version of modern Hungarian history. That is, they get the national democratic narrative of 1956.

While 1956 plays a central role in the exhibition, Imre Nagy is clearly not its symbolic hero. Rather, the hero is the nation. "From 1944 to 1990, our nation was robbed of its independence and freedom,” says Schmidt in introductory remarks posted on the museum's website, "first by Arrow Cross thugs supported by German Nazis, and then by communists backed by the Soviet Union. We have since recovered both our independence and freedom, to become free citizens of an independent Hungary. Because we Hungarians are a people of freedom!”

In contrast to the dominant narrative in Western academia, where nationalism is the first suspect in every modern political catastrophe, in Schmidt's version, nationalism is the bedrock of democratic freedom, opposing the two forms of totalitarianism in Hungary that were propped up by foreign powers. The story of the exhibition emphasizes continuity between Nazi-backed Arrow Cross totalitarianism and the communist dictatorship that followed it. The room that separates the Arrow Cross section from the communist section is themed around turncoats: Often, the exhibition says, Hungary’s Nazis and communists were the same people. Both groups' use of the same headquarters underlines this theme concretely. The implications for contemporary politics are clear: Since the exhibition strongly suggests that nationalism is the foundation of democracy and freedom, it is unlikely to produce globalist sympathies or cultivate much love for the European Union. The sentiment is requited: The European Union is anything but friendly toward Orbán's government. In fact, much of Orbán's image as an authoritarian bogeyman emanates from Brussels, which continuously scrutinizes Hungary’s credentials as a rule-of-law democracy.

Placing communist crimes and Nazi genocidal antisemitism on par in the House of Terror has caused outrage especially in Jewish institutes devoted to commemorating the Holocaust, including the Simon Wiesenthal Center and Israel’s Yad Vashem. Schmidt has been criticized, with some merit, for downplaying Hungarian complicity in the Final Solution. But any attempt to bill this to antisemitic views is, as far as I can tell, misguided. Schmidt is a Fidesz devotee, and Fidesz is strongly pro-Zionist and philosemitic. In fact, the affinity between Fidesz's ideology and Zionism makes sense, and it is no coincidence that Hungary is Israel's most steadfast supporter in the European Union: On the contemporary global scene, both Zionism and Hungarian nationalism share a common insistence on self-determination in direct opposition to globalizing forces. Both are therefore vilified as obstacles to progressive globalism.

Much of the liberal media in the West, when not explicitly antisemitic, casually assumes that the sovereigntist right is. So if Orbán is on the right, he's obviously a "dictator" and a "fascist" and therefore must also be antisemitic. Yet as Tamir Wertzberger, director of foreign affairs at the Action and Protection League, an organization devoted to combating antisemitism in Europe, located in Budapest and financed by the Hungarian government, notes, "Orbán has launched a zero-tolerance for antisemitism policy, and consequently the number of antisemitic incidents in Hungary dropped dramatically. Budapest is perhaps the single safest place for Jews in Europe."

Wertzberger may be paid by the Hungarian state, but he is not wrong. Prague in the Czech Republic is probably the only European city that can compete with Budapest as a place where a Jew wearing a kippah can walk in the streets unmolested and without fear. And not surprisingly, both are capitals of countries that have resisted the pressure to accommodate illegal Muslim immigration.

There is, however, an actual neo-Nazi party in Hungary: Jobbik. And while the Hungarian left had no qualms about incorporating Jobbik into the anti-Orbán bloc in the last national election, Orbán himself has been consistent in refusing to let them into his coalition.

In the eyes of his critics, Orbán is the "illiberal" menace to liberalism. Ironically, the unfortunate term "illiberal state" was Orbán's, coined in a speech he gave in Romania in 2014, in which he used it to describe his vision for Hungary. But Hungary is not really illiberal in any meaningful sense, unless one means anti-woke. But the PR damage from that label has been done. Among other things, it enabled Orbán's adversaries—not least in Brussels—to portray him as an enemy of democracy. In fact, it's the exact opposite of its intended meaning: that liberalism, in its woke mutation, has turned against both freedom and democracy in much of the West, especially in the European Union, where principles are imposed from above in the name of liberalism, thus violating the basic democratic principle of government by consent of the governed.

The rise of an anti-democratic form of transnational progressivism, predicts John Fonte in his landmark book Sovereignty or Submission, is likely to be the central political struggle in the West in the 21st century, pitting progressive globalism against the sovereignty of national democracies. We see this battle not only in Hungary, but also throughout the West—most conspicuously in Israel, the United States, and Britain. Is it any wonder, then, that this small country has become a trailblazer for those on the so-called populist right who want to see democracy revitalized?

Park MacDougald is a treasure, always able to connect associations and bring to light what is going on the world and national scene. Lots of folk trying to insert Obama/Biden policies into the current administration, which ran and won on a platform distancing itself from Obama/Biden. Hoping Trump sees the light and distances himself from tucker carlson and his group of Obama/Biden policy loving wonks.

Man oh man, it’s getting harder and harder to keep track of the players these days. So much duplicity, so little time.

And the stakes could not be higher.

God have mercy on us all.