March 5: Children Cannot Consent to Transition, Trans Health Experts Admit

Mr. Gantz goes to Washington; UN admits Israeli women were raped, are being raped; VA backpedals after declaring war on victory, joy, history, America

The Big Story

Leaked internal communications from the World Professional Association for Transgender Health, which produces the widely influential “Standards of Care” for treating gender-related distress in adults and children, show WPATH members admitting that children are unable to understand the consequences of the “gender-affirming” treatments that WPATH recommends; that these treatments are frequently provided with minimal evaluation by doctors who don’t “necessarily know everything about trans care”; and that WPATH-affiliated clinicians prize short-term subjective well-being over long-term patient outcomes, despite the medically serious and potentially fatal complications that result from hormonal and surgical treatments.

The documents also show WPATH members advocating gender-transition treatments for “developmentally delayed” adolescents and patients with severe psychiatric disorders. For instance, Dr. Dan Karasic, who authored the mental-health chapter of WPATH’s most recent “Standards of Care,” described a “genderqueer” male with bipolar disorder, alcohol use disorder, and dissociative identity disorder undergoing “flat front” nullification surgery—i.e., the removal of genitals to create a “sexless” appearance. Karasic reassured his audience that all seven of the patient’s “alters” (or personalities) were in agreement about the surgery, including two “agender” alters. Another gender therapist said that in 15 years they had only once, “regrettably,” declined to write a recommendation letter for genital surgery—in the case of a patient who was in “active psychosis” and “hallucinated” during the assessment. Other messages show surgeons discussing performing vaginoplasties on children as young as 14 years old, while still others reveal doctors resorting to extreme forms of body modification, such as “gender nullification” and “mastectomies without nipples,” for patients whose “embodiment goals do not fit dominant expectations.”

The revelations come from a new report, “The WPATH Files,” published Monday by journalist Mia Hughes and environmental organization Environmental Progress. According to the report’s executive summary, these internal communications “reveal that WPATH advocates for arbitrary medical practices, including hormonal and surgical experimentation on minors and vulnerable adults,” in full knowledge of the risky, experimental nature of these procedures and of their patients’ inability to comprehend or consent to these treatments’ consequences.

These internal communications are particularly damning when contrasted with WPATH’s public stances on gender-affirming care for children and adolescents. For instance, WPATH President Marci Bowers said in 2023 that state laws banning such “medically necessary” procedures for minors were about “eliminating transgender persons on a micro and macro scale” and “a thinly veiled attempt to enforce the notion of a gender binary.” At a 2022 internal WPATH workshop panel, however, senior WPATH members frankly admitted that children were not psychologically equipped to understand the consequences of these procedures. Daniel Metzger, a Canadian endocrinologist, reminded attendees that they were “explaining these sorts of things to people who haven’t even had biology in high school yet,” while child psychologist Dianne Berg added that for young patients, it is “out of their developmental range to understand the extent to which some of these medical interventions are impacting them.” Berg also conceded that she was “stumped” by the question of how 9-year-olds could understand lifelong fertility loss, a known side-effect of cross-sex hormones.

Although the Biden administration has attempted to expand gender-transition treatments for children and adolescents, including by suing states attempting to ban it and introducing an executive order prohibiting federal funding for so-called conversion therapy (i.e., when a therapist attempts to help a gender-dysphoric patient accept their biological sex), the United States is increasingly an outlier in the Western world in its approach to treating gender-dysphoric youth. In recent years, Denmark, Finland, Sweden, and the United Kingdom have all sharply restricted “gender-affirming care” for minors after medical reviews have found little scientific support for its efficacy.

Read more here: https://environmentalprogress.org/big-news/wpath-files

IN THE BACK PAGES: Seth Kaplan on the lessons that the Jewish model of embodied community can offer to a divided America

The Rest

→Israeli war cabinet minister and opposition leader Benny Gantz has been in the United States since Sunday, meeting with Vice President Kamala Harris and National Security Advisor Jake Sullivan on Monday and Secretary of State Antony Blinken on Tuesday, in a trip that has reportedly angered Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu. Bibi is likely right to worry: It’s well known that the Biden administration would prefer Gantz to run Israel, and by meeting with Gantz, “the administration is sending an unmistakable signal of unhappiness with Benjamin Netanyahu,” as the former diplomat Aaron David Miller told The Wall Street Journal.

Gantz no doubt agrees with the Americans that he should be prime minister; the problem is what they’ll want him to do once in office. Harris reportedly spent her Monday meeting hectoring Gantz about the administration’s “deep concerns about the humanitarian situation in Gaza” and Israel’s need to produce a “credible and implementable humanitarian plan” for civilians in Rafah, with Israel National News reporting that White House officials “expressed great doubt” as to whether Israel could successfully produce such a plan (translation: don’t invade). Gantz reportedly pushed back, explaining that “ending the war without clearing out Rafah is like sending a firefighter to extinguish 80% of the fire,” rejecting American plans for the Palestinian Authority to return to power in Gaza, and arguing that Hamas was the main obstacle to the delivery of more aid.

According to Barak Ravid’s Tuesday report in Axios, last week’s aid-convoy disaster was “a turning point” for the Biden administration, which saw it as embodying “all the Israeli policy failures in Gaza.” Ravid goes on:

A senior Israeli official said that already after the meetings Gantz had on Sunday to prepare for the meetings with White House and State Department officials, the Israeli minister started realizing the Israeli government “is in deep shit” when it comes to how the U.S. sees Israel’s responsibility for the humanitarian crisis in Gaza.

Ravid further reported that “Gantz wasn’t only surprised by the strength of criticism about the humanitarian crisis but also about how far apart Israel and the U.S. are when it comes to a possible operation in Rafah.” Or, as Caroline Glick put in on X:

The core issue is that the White House wants to blame Netanyahu and his “hard-line” coalition partners for spoiling Washington’s plan to court Iran—while hurting Biden’s popularity with the lunatic fringe of the Democratic Party—by refusing to end the war on American terms that would leave Hamas in power. By scapegoating Netanyahu and holding up Gantz as an alternative, the White House can signal to Jews in the United States (and liberal Zionists in Israel) that their issue is not with Israel per se but with the Netanyahu government. As Gantz is discovering, however, Washington’s core demands would be unacceptable to Israel, the Israeli public, and any Israeli politician with ambitions of leading the country. Which is why he’s now in Washington explaining to his would-be patrons that no Israeli leader could accept their terms and survive.

→This dawning realization on the part of the Israeli political establishment helps explain why we keep seeing stories like this:

→Apropos of our Big Story yesterday on The Intercept’s “clean Wehrmacht” theory of Hamas and the Oct. 7 sexual assaults, the U.N. envoy on sex crimes presented a report on Monday acknowledging that rape and gang rape likely occurred on Oct. 7 and that there is “clear and convincing” evidence that Hamas has raped and continues to rape Israeli female hostages in Gaza. The envoy, Pramila Patten, who had visited Israel and the West Bank to meet with Israeli officials, witnesses, survivors, and first responders, said there were “reasonable grounds” to believe that rape and gang rape occurred on Oct. 7 and “clear and convincing information that sexual violence including rape, sexualized torture, cruel, inhuman and degrading treatment” was perpetrated against the hostages, according to a report in The Times of Israel.

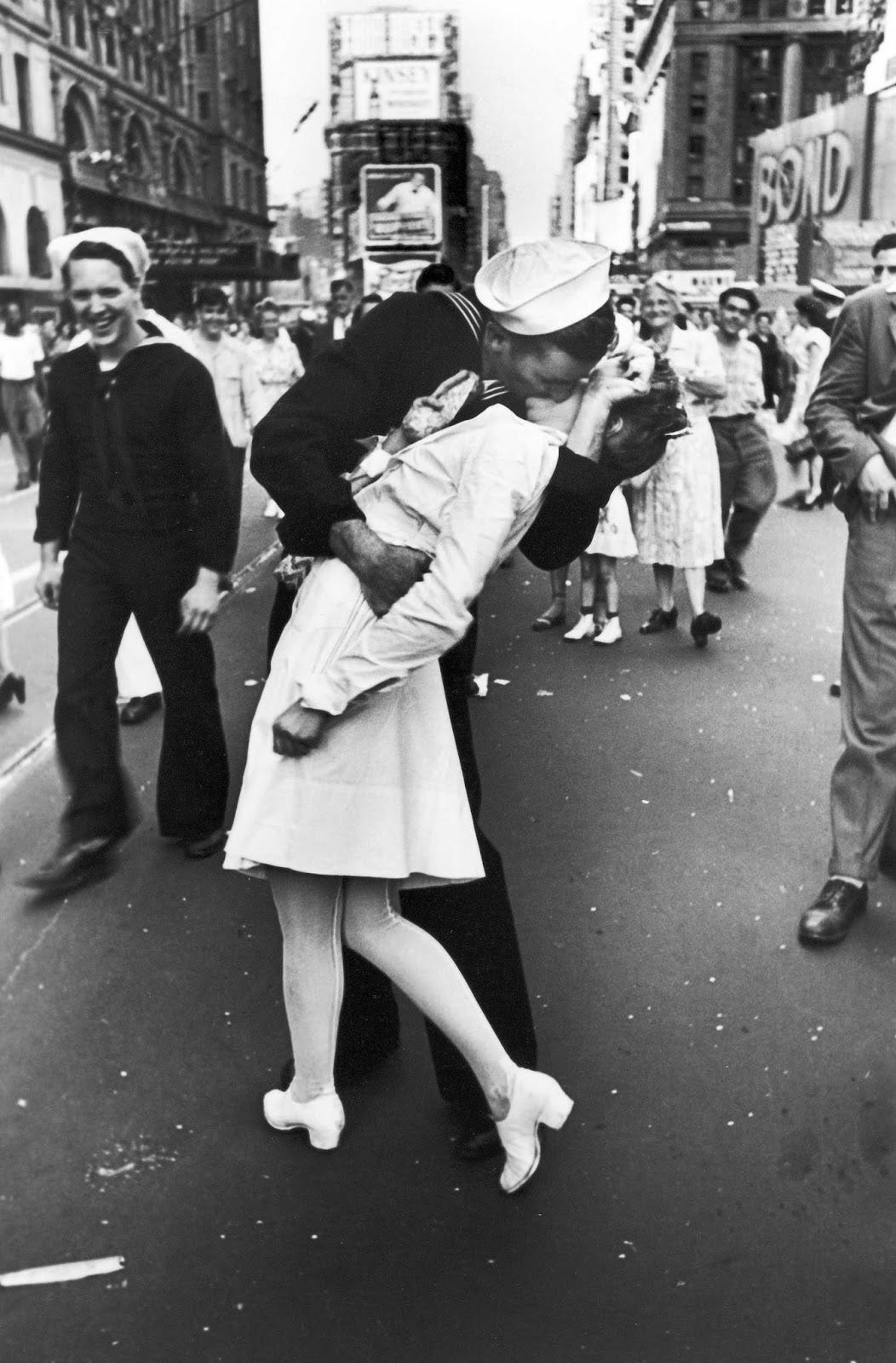

→Image of the Day:

That’s “V-J Day in Times Square” by photographer Alfred Eisenstaedt, which shows a sailor, George Mendonsa, spontaneously kissing a stranger, believed to be Austrian-Jewish émigré Greta Zimmer Friedman, in Times Square after the announcement of Japan’s surrender on Aug. 14, 1945. On Feb. 29, 2024, RimaAnn Nelson, assistant undersecretary for Health for Operations in the Veterans’ Health Administration of the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs (VA), sent a memo requesting the removal of the photograph from all VHA buildings “in alignment with the [VA’s] commitment to maintaining a safe, respectful, and trauma-informed environment.” According to the memo, “This action is promoted by the recognition that the photograph, which depicts a non-consensual act, is inconsistent with the VA’s no-tolerance policy toward sexual harassment and assault.”

Shortly before The Scroll published on Tuesday, The Washington Post reported that VA Secretary Denis McDonough had rescinded the memo in response to outcry on social media.

→The FBI is hunting for an Iranian intelligence officer believed to be plotting to assassinate former U.S. Secretary of State Mike Pompeo and other current and former U.S. officials, according to a Monday report from Semafor’s Jay Solomon. On Friday, the FBI’s Miami field office issued a public alert seeking information on Majid Dastjani Farahani, who speaks Spanish, “frequently moves between Iran and Venezuela,” and has allegedly been “recruiting individuals for operations in the U.S.” (The Biden administration has granted Temporary Protection Status to nearly 500,000 Venezuelans who have illegally entered the United States since January 2021.) Solomon also notes that the Department of Justice is “still investigating” whether the Iran-sympathizing, Lebanese American assailant who stabbed novelist Salman Rushdie in 2022 was acting “directly under Iran’s orders.” But given the administration’s perpetual inability to determine whether Iranian proxies attacking U.S. and allied forces under the direction of Iranian officers are acting “directly” under Iran’s orders, we won’t hold our breath.

Read it here: https://www.semafor.com/article/03/04/2024/fbi-hunts-for-suspected-iranian-assassin-targeting-trump-era-officials

→Teachers at a New York City Department of Education “anti-Muslim bias” training learned that jihad means “struggle” or “great effort,” not “holy war,” and that sharia refers to “personal religious and moral guidance,” not “law.” The host of the Feb. 20 webinar “Understanding Muslim Experiences and Combating Anti-Muslim Bias” explained that “jihad is the Muslim concept of striving in the path of God” and promoted a #MyJihad hashtag campaign, with examples such as “my jihad is to never settle short” and “my jihad is to build friendships.” Such an understanding would, we expect, be news to most Muslims throughout history, including the great historian Ibn Khaldun, who wrote in The Muqaddimah, “In the Muslim community, the holy war [jihad] is a religious duty because of the universalism of the Muslim mission and the obligation to convert everybody to Islam either by persuasion or by force.”

SCROLL TIP LINE: Have a lead on a story or something going on in your workplace, school, congregation, or social scene that you want to tell us about? Send your tips, comments, questions, and suggestions to scroll@tabletmag.com.

Four Lessons for a Fragile America

The Jewish model of embedded community offers something unique to an America that badly needs it

By Seth Kaplan

The United States’ sprawling geography has long encouraged the dispersion of people, but since World War II we have buoyantly pursued an American dream that has so disconnected us from each other that it is starting to look like an illusion. We’ve been allured by the siren songs of individual autonomy, national economic growth, and modernist utopian planning. These are fueled by consumption and carried out at a scale that discourages and distracts us from being persons in space and time. Today, physical landscapes are designed for vehicles rather than relationships, and many neighbors have nothing in common with each other besides geography. Our smartphones and other devices make us feel that we inhabit a digital space—a space that makes promises about belonging that it cannot keep.

The result of all these changes is predictable: We have endless choices, and yet feel alienated from our surroundings because we do not belong anywhere and feel powerless to do anything about our circumstances. Individuals experience growing anxiety, anomie, anger—and our society suffers from mistrust and polarization of our politics. The health of Americans has been declining relative to other developed countries for over four decades, a trajectory that significantly worsened in the 2010s (that is, pre-COVID). While we often talk about economic inequality, social inequality—differences in how much one is supported or held back by one’s family, neighbors, friends, and social network—is arguably a much larger problem.

Social dysfunction is most apparent in distressed neighborhoods in large cities—places where poverty is high, marriage is rare, housing is miserable, streets are unsafe, good models are absent, and kids struggle to get through high school and see optimism in their futures. But some of the worst social indicators can be found in rural areas, such as Appalachian Kentucky, where economic collapse has combined with the drug epidemic to devastate families, local institutions, and whole counties.

That, alas, is not the whole story. Social decay and disconnection extend into the most middle-class and affluent areas of the country. For too many, upward mobility has also been an engine of isolation and alienation. Outsourcing care for our children, elders, and even ourselves to others may seem like a perfectly rational—if not obligatory—way of managing various challenges efficiently. But John McKnight and Peter Block, authors of The Abundant Community, cite this rise in professional “purchase care” as a replacement for “freely given commitment from the heart” as one reason why even neighborhoods that are economically well off can be socially impoverished, and fragile.

One notable exception to these trends is Orthodox Jewish communities, which retain embodied and embedded practices and the institutions that sustain them. While offering ample opportunity for individuality, Judaism makes place-based community the main organizing structure of life in a way that no other faith does. It does this by marking both time and space in distinct ways. The fruit of these boundaries can be seen in any Orthodox area—where the degree of interaction between people stands in sharp contrast to just about any other place in America.

While Shabbat and festivals bring us closer together, a whole slew of overlapping institutions—some clearly religious (synagogues, mikvot, schools, batei din), others less so (kosher restaurants and markets, gemach loan societies, charity funds, after-school activities, interfamily support groups)—embed our lives in social relationships, groups, and activities that not only provide meaning and companionship, but sustain or propel us at critical junctures. Together, they nurture a sense of trust, willful interdependency, and security that is too often missing in other American neighborhoods.

Members of my tightknit community in Silver Spring, Maryland, for example, regularly volunteer to help one another—delivering groceries to an elderly member of our neighborhood, picking up packages when a neighbor is away, chaperoning at school events, mentoring youth, hosting playdates, joining park cleanups, and bringing medicine to someone who has fallen ill. Everyone—regardless of their financial situation—contributes money and time to community organizations on a regular basis, often in leadership roles (I sit on the board of directors of one such organization). Notably, we spend surprisingly little time talking about politics (beyond our support for Israel), and thus avoid a topic that divides so much of the country.

Observant Jews belong to a place and to each other in a way that was once commonplace—but now is rare. By ensuring our daily lives are shaped by a thick set of institutions and practices that form individuals into persons, closely tied to other persons, our faith makes us more resilient amid the unfettered forces of modernity, the insatiable demands of the market, and the anonymous machinations of the state. Community cohesion is critical in an era of atomization and social decay—not only for preserving the faith tradition but for the flourishing of each person in it.

American Jewry often debates what its role should be in the wider society. Some seek an activist path, others a political, while yet others look to philanthropy. In all cases, we are inclined to believe that the best way to contribute is by actively engaging in a big “cause” or whatever the media designates as a “national priority.” While we do consider how our efforts are grounded in Judaism’s values, we rarely reflect on whether such efforts are grounded in our local practices. And yet, the Jewish model of embedded community offers something very specific—and unique—to an America that badly needs it.

While every kind of contribution is important, I think what we might offer our country at this difficult time is not increased donations or campaigning but new thinking and action that leverages the best lessons from our own tradition of building the world’s most successful place-based communities.

Nothing would revitalize American society more than a renewed emphasis on embodied relationships, especially those that are place-based such as families, children, and neighbors—and a concomitant commitment to significantly boost the neighborhood social institutions and norms, including those around family and marriage, that support these. And by strengthening our local identity and social ties, we can do what Mack McCarter, founder of the nonprofit group Community Renewal International, calls “re-villagize the city”: working to bring neighbors together and countering the various forces in contemporary society that work to pull them apart.

***

Practically speaking, here are four broad lessons we can draw from the Jewish experience to make place-based community great again in America:

First, the physical landscape matters. It’s easier to build a strong Jewish community where homes are relatively near each other—close-by synagogues and kosher restaurants make it easier to congregate, and walkable streets and an eruv make going between homes and synagogues effortless. Urban and suburban planners should focus on promoting the kind of physical landscape that nurtures social cohesion as an integral part of their primary task, rather than ignoring how their designs influence common life, as is the case today. This means reenvisioning our physical landscape around clearly demarcated neighborhoods, with more densely built, multiclass, multifunction housing and public spaces that encourage social interaction, civic-mindedness, and a sense of loyalty to one’s neighbors and community. Fountains, churches, local associations, commercial streets, libraries, parks, public buildings, and community centers all provide “third places” where we can interact with others from our immediate surroundings.

The New Urbanism movement, which arose in the early 1980s to address the ills of the car-centric isolating sprawl brought on by the post-Second World War development model, has advanced many of these causes, but it does not go far enough. Its focus on density, mixed-use, and walkability points us in the right direction, but is an incomplete vision: Only spatial boundedness and a thick set of institutions can restore social vitality.

Second, an abundance of overlapping institutions and networks fuel the close ties that make life in a Jewish place-based community so socially vital. How could this translate to other places? Government, business, religious, philanthropic, and nonprofit leaders should be rethinking every aspect of their organizations so that they are much more focused on and deeply embedded in neighborhoods. For government, this means both shifting authority over programs and money from national to local control and shifting them from hierarchical silos to neighborhood-focused teams. Instead of sector-specific experts working distantly from those on the receiving end of programs, our cities and towns need generalists with a wide range of skills who are committed to a particular geography for an extended period of time. Then we could evaluate local teams based on the success of their neighborhoods, not the subsidies dished out, permits issued, roads completed, or boxes checked—as is typically the case today.

Similarly, nonprofits and philanthropy might move away from a focus on specific goals (e.g., education, housing, health, security, food, and work) and instead concentrate on improving the relational dynamics that make interventions necessary in the first place and limit their effectiveness once undertaken. Religious leaders should try harder to be countercultural, building close-knit, place-based communities with all the obligations that entails instead of being just another consumer product satisfying the needs of congregants—a very thin vision for what faith looks like in daily life, in person.

Third, family is also one of the greatest incubators of other neighborhood relationships, which grow organically out of school pickups, play dates, parent groups, and other activities that lighten the daily load and bring people together. While a focus on making family formation and the raising of children easier typically leads to an emphasis on policies such as parental leave, altering the tax code, health care, and making young men more marriageable, the lesson from Orthodox Jews is that what matters most is not government policy, but the nature of the surrounding community context. Does it promote marriage and large families or not? What would make the context more amenable to these? Here are a few ideas: more flexible work and school schedules, more acceptance of pregnancy and babies in public and professional meetings, the development of child-friendly playgrounds every few blocks, more multigenerational homes and neighborhoods, and more proactive efforts by leaders—including by example—in every sphere to promote the positive benefits and pure joy that a lifelong commitment to another person and parenthood brings.

Israel, which has by far the highest birth rate among developed countries (including among the nonreligious), exemplifies these elements, as any walk through an Israeli neighborhood or office will attest. In America, many religious groups have created similar ecosystems that enable family thriving—beyond Orthodox Jews, there are Amish communities, Mormon wards, and Catholic parishes, for example—but it’s still far from the norm.

Fourth, community schools and neighborhood kids’ activities play crucial roles bonding a community together in Orthodox Jewish neighborhoods. In any American neighborhood, there is likely no secular institution better at bringing neighbors together than local community schools. They create interfamily networks, play groups, and platforms for neighbors to meet and collaborate. Yet, rarely do we as a society think of schools as playing a crucial role strengthening society—too often debates on education policy are fixating on quantitative measures as if each student was a unit in a factory. Instead, we should ensure that every neighborhood has at least one—and ideally two or three for the sake of competition—local schools that students can walk to and make friends that live nearby.

Informal and spontaneous connections matter, too. Every neighborhood should foster opportunities for kids to play with each other—ideally in unstructured, unsupervised ways—as Jon Haidt has recommended. He argues that many of the problems youth are having today is because we have moved from “play-based childhood” to a focus on “safetyism”—defined by “over-supervision, structure, and fear.” Youth are arguably the most important demographic for any attempt to reverse social disconnection—they need to experience the joys of embodied life and communal institutions and not just see them as empty vessels and rhetoric. When summer camps and neighborhood after-school activities practice warm, welcoming engagement, it encourages stickier, longer-lasting commitments. Student government and clubs offering opportunities for serving the school and neighborhoods can impart the practice of stewardship and interpersonal responsibility.

***

Regardless of whether we live in an Orthodox Jewish community or not, we can each promote the ideas Jewish tradition has cherished and in turn have helped sustain the Jewish people over thousands of years as well as present positive models of living to support families and neighborliness. Alexis de Tocqueville noted, “The love and respect of your neighbors must be gained by a long series of small services, hidden deeds of goodness, a persistent habit of kindness, and an established reputation of selflessness.”

It is difficult to envision an alternative way of life if you haven’t had a good look at it. We can all work to offer a better glimpse into our embodied and embedded traditional practices, and into the institutions that sustain them. Orthodox Jewish communities like mine can stand as a beacon for the beauty of place-based boundaries. We should be writing about what makes our practices special more often, looking for lessons in them for wider society, and offering a way for others to at least get a firsthand glimpse into what makes our communities so remarkable.

More broadly, we can reconsider our own values and choices. Instead of passionlessly donating money to a faraway charity with millions of people on their mailing list or getting involved in a national political cause with a large and vocal following online, do something local, something that contributes in a tangible—even if tiny—way to a real place and to real people. We can also extend these principles to our professional spheres. For example, we can reexamine how our institutions and policies work and ask whether they can put the neighborhood and its relationships and institutions center stage.

Our social ills are unlikely to be healed without restoring the scale of human relations that makes us more fully human. “The only way to maintain ‘real and sincere closeness’ with a person,” Tim Carney writes in Alienated America, “is to entangle ourselves with that person through the bonds of an institution—to live in community and to work toward common ends with that person.” With rhythms and institutions that attach us to a place-based community, Judaism shows us many ways how this might be done.

Imagine being lectured to by Kamala Harris and Jake Sullivan. And being told of your “policy failures” by the people behind the Afghanistan withdrawal fiasco. Gantz should have stayed in Israel.

As was the case in 1973, we are seeing that Israel's success in this war is driven by the grunts on the ground whose start up ethos is redeeming the good name of the IDF , protecting Israel and lfighting without kow towing to the US, as opposed to grandiose plans formulated by the brass.