May 30: What Is Trump Even on Trial For?

Biden-Zelensky tensions; Iran sponsors grenade attacks in Europe; Gender inclusive genetics

The Big Story

A note to readers: The Scroll will be on vacation Friday as its author attends a wedding.

Shortly before The Scroll closed on Thursday—though by the time you read this the news might have changed—the jury in Donald Trump’s Manhattan criminal trial was still locked in its second day of deliberations. At issue is whether Trump—who is, as of now, the front-runner in the November election—will become the first former president to ever be convicted of a crime after leaving office (he’s already the first to be charged). What crime? Well, on that score, we’re confused, much of the rest of the media is confused, and apparently the jury is confused, too, since it’s had to ask multiple times to be reminded of its instructions (in one of the many Kafkaesque turns of the trial, the judge, Juan Merchan, has not allowed the jurors to receive written copies of the jury instructions). Still, we’ll do our best.

Trump faces 34 felony counts of falsifying business records for categorizing as “legal expenses” the reimbursements he made to his lawyer, Michael Cohen, for hush money payments to a porn star whom Trump allegedly slept with. Now, one might argue that paying your lawyer to arrange an NDA is, in fact, a legal expense, if an unsavory one, but let’s roll with it. The bigger problem is that falsifying business expenses is a misdemeanor in New York, with a two-year statute of limitations. The alleged crime took place in 2017, six years before Manhattan District Attorney Alvin Bragg filed charges last April. But this misdemeanor can be raised to a felony with a six-year statute of limitations if it was done in furtherance of another crime—which is exactly what Bragg has alleged.

The exact nature of the other crime, however, was not specified until closing arguments earlier this week. On Tuesday, prosecutors finally revealed that the other crime was … drumroll … a violation of a New York state election law that makes it a misdemeanor to “conspire to promote the election of any person to public office by unlawful means.” So the other crime is also a misdemeanor, which is only a crime if it involves another crime—in this case, whatever crime makes the election conspiracy “unlawful.” So what crime is that? Here, Merchan told the jury they could take their pick between three options: (1) a violation of the Federal Election Campaign Act (FECA); (2) New York tax fraud; and (3) falsification of other business records—which would mean that Trump falsified business records to conspire to steal the election by falsifying business records.

In closing arguments, the prosecution leaned heavily on option 1, the FECA violation, on the theory that the NDAs were unreported campaign expenditures, since news of Trump’s affairs would allegedly have hurt his campaign. Put aside for the moment that FECA can, by law, only be enforced by the Federal Election Commission and the Department of Justice, both of which declined to prosecute Trump, and consider this: In 2022, the Hillary Clinton campaign and the Democratic National Committee agreed to pay $113,000 in civil penalties to settle an FEC investigation into whether they misreported campaign expenditures. What was the alleged violation? It was that the Clinton campaign and the DNC had paid law firm Perkins Coie to hire Fusion GPS for the opposition research that eventually became the Steele dossier—and had reported these payments as “legal expenses” rather than campaign expenditures. For reasons we can’t quite fathom, no state-level DA thought to inflate this alleged violation into a 34-count felony criminal indictment.

Writing in National Review, former federal prosecutor Andy McCarthy predicts that the trial has been so mismanaged by Judge Merchan—a Biden donor whose daughter, a Democratic consultant, earned $9.7 million from the Biden-Harris campaign in 2020, according to reporter Paul Sperry—that the jury may well return a conviction that will later be tossed on appeal. The American people, however, seem to be taking the trial with the seriousness it deserves. A recent poll from Quinnipiac University, highlighted by Harry Enten on CNN, showed that 46% of Americans believe Trump did something illegal with the hush money payments before the trial started, and 46% believe he did so now. That suggests that the effect of Bragg’s circus trial on Americans’ voting intentions has been precisely zero—zip, zilch, nada.

IN THE BACK PAGES: Israel’s greatest strategic failure wasn’t October 7, argues Michael Makovsky. It’s the failure to act in Lebanon

The Rest

→The United States is expected to sign a bilateral security agreement with Ukraine during next month’s G7 Summit in Italy, according to a report in the Financial Times. The report offers few details on the substance of the agreement, but our guess is that it’s the White House’s consolation prize to Ukraine for the lack of progress toward Ukrainian membership in NATO—one of the sources of the conflict between Biden and Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskyy that is the real subject of the article. Among Zelenskyy’s complaints are the delay in U.S. military aid, the U.S. prohibition on Ukraine’s use of American weapons inside of Russia, U.S. pressure on the Ukrainians to cease their drone strikes on Russian oil infrastructure, and Biden’s decision to skip Ukraine’s peace summit on June 15 and 16 in favor of a Democratic fundraiser. According to the report, Zelenskyy suspects that Biden wants to sell out Ukraine to make the war go away before the election in November, which is probably true. But we’d add is that the administration, despite its florid anti-Russian rhetoric, still needs Putin to act as a guarantor for any future deal with Iran—which requires preventing the Ukrainians from doing anything to really hurt him.

Separately, the Financial Times reported Thursday that NATO has less than 5% of the air-defense systems needed to protect its Central and Eastern European members from an attack, according to sources familiar with confidential NATO defense plans from 2023.

→European criminal organizations working on behalf of Iran are responsible for recent attacks on Israeli embassies in Europe, according to a Thursday statement from Mossad first reported in Haaretz. One of these criminal organizations, Foxtrot, led by a Swedish citizen of Kurdish descent named Rawa Majid, is believed by Swedish authorities to be responsible for a grenade attack against the Israeli embassy in Sweden in January and for another on the Israeli embassy in Belgium this past weekend. According to Haaretz, Iranian police arrested Majid after he fled to Iran from Turkey in 2023; he was released on the condition that he use Foxtrot, the largest criminal network in Sweden with branches in several other countries, “to promote terror attacks against targets in Europe, with an emphasis on Israeli and Jewish targets.” Mossad also noted that several men, some of them Iranian, had been arrested in connection to a shooting incident at the Israeli embassy in Sweden earlier this month. The arrestees were connected to another criminal network, Rumba, led by a man named Ismail Abdo (a “rival” of Majid’s), which is also acting at the behest of the Iranians.

→But while the ayatollahs may sponsor terror around the world, they at least have a sense of humor:

→In Europe, Iran is recruiting criminals to attack Jews; in Brooklyn, loonies will do it for free. On Wednesday, a deranged cab driver attempted to run over Orthodox men outside of a Brooklyn Jewish school—while yelling “Kill all Jews,” just in case anybody mistook his intentions. The suspect, Asghar Ali, 58, is a Pakistani immigrant with a rap sheet for erratic and disturbing behavior dating back to 2007. Following the broad-daylight attack in Brooklyn’s Flatbush neighborhood, which was captured on security cameras, Ali was tracked down by members of the Shomrim Safety Patrol, who stood by while the NYPD made the arrest. Ali has been charged with attempted assault as a hate crime, vehicular assault, menacing, and unspecified “other charges,” according to a report in the New York Post.

→Image of the Day, Part I:

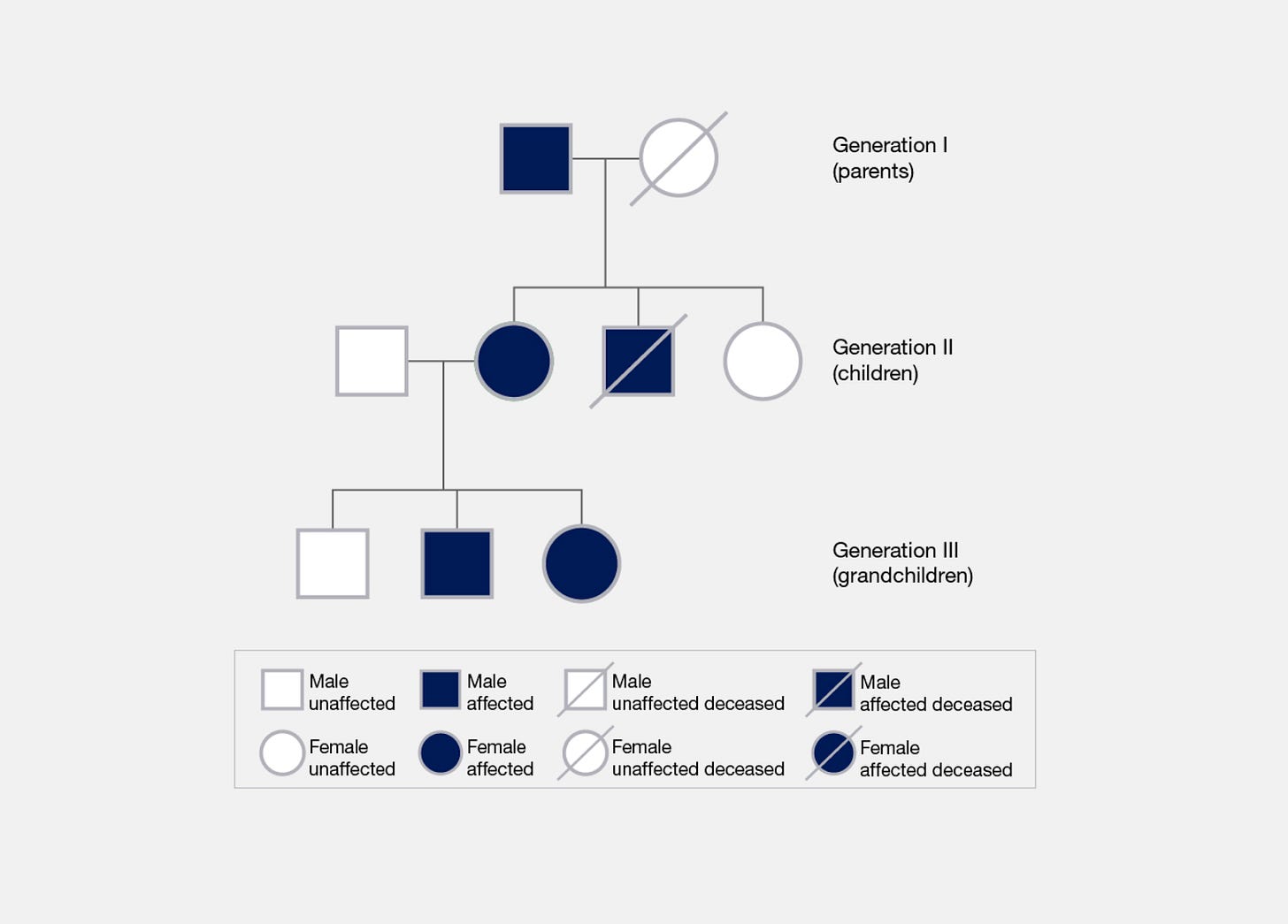

That’s a sample pedigree chart, which “diagrams the inheritance of a trait or health condition through multiple generations of a family,” taken from the website of the National Human Genome Research Institute, a division of the National Institutes of Health. Males are represented by squares and females by circles.

→Image of the Day, Part II:

That’s a sample “Gender Identity Inclusive Pedigree Chart for High School Biology” taken from the website of the National Science Teaching Association. “Science teachers,” write the creators of the chart, Sal Kaczowska and Susan Groziak, “have an opportunity and obligation to acknowledge and respect their bisexual, transsexual, and intersex students by employing a modified inclusive pedigree chart.” The chart was brought to our attention by X user @WomenAreReal, who described her teenage son being told by a biology teacher at his Bay Area high school to mark “male” and “female” as “AMAB” and “AFAB” on his pedigree chart and to represent nonbinary people as diamonds.

→A message in a private Facebook group for Chicago therapists asked whether any would be willing to see a “Zionist” client; when several Jewish therapists responded that they would, they were added to a no-referral blacklist of “clinicians who promote and facilitate white supremacy via Zionism” maintained by a second group of “antiracist therapists.” The anecdote comes from a Thursday report in Jewish Insider about antisemitism in the mental-health profession—although, we should note, this explicitly anti-Jewish turn follows years of mental-health and therapy graduate programs proclaiming their commitment to use therapy to undo “systemic white supremacy” (in the words of the University of Vermont’s graduate counseling program in 2021), including by berating white clients to acknowledge their “privilege” and “unconscious bias.”

Read the Jewish Insider report here.

→South Africa’s ruling African National Congress Party looks set to lose its parliamentary majority for the first time since the end of apartheid in 1994, according to early results from Wednesday’s election. As of Thursday afternoon, the ANC was sitting at 42.3% of the vote—a plurality, but not enough to form a government without a coalition. The center-right opposition Democratic Alliance was second, with 25%; the far-left Economic Freedom Fighters sat at 9%; and several smaller parties, including former President Jacob Zuma’s uMkhonto we Sizwe, accounted for the remaining quarter of the vote. While the ANC is still expected to remain the largest party, the result marks a steep drop in support since 2019, when the party won with 57.5% of the vote. During the tenure of the incumbent ANC President Cyril Ramaphosa, the country has seen rolling electricity blackouts and average economic growth below 1% per year. Analysts quoted in the Financial Times also attributed the ANC’s worse-than-expected performance to a new law banning private health insurance for any treatments covered by a proposed national insurance fund.

TODAY IN TABLET:

The Spy Who Never Came in From the Cold, by Gordon Thomas

The horrifying death of the CIA’s Beirut station chief at the hands of Hezbollah

SCROLL TIP LINE: Have a lead on a story or something going on in your workplace, school, congregation, or social scene that you want to tell us about? Send your tips, comments, questions, and suggestions to scroll@tabletmag.com.

Israel’s Great Strategic Failure

It wasn’t October 7. It's the continuing avoidance of military action against Hezbollah in Lebanon.

by Michael Makovsky

It has become conventional wisdom after Oct. 7 that Israel for years had the wrong policy toward Gaza. While the unfathomable catastrophe of that day has rightly forced a critical examination of all the factors that led to it, it’s arguable that Israel’s broad pre-Oct. 7 policy toward Gaza, in contrast to its strategic conception and military preparation, was at least understandable, if not correct. In contrast, there has been less criticism of Israel’s policy toward Hezbollah in Lebanon over the past two decades. Not only does the policy toward the northern front raise even more troubling questions than Gaza, but also, now more than ever, it looks like a major strategic failure.

Ever since Hamas took control of Gaza by force in 2007, Israel has fought several small wars with the genocidal terrorist organization, in response to rocket attacks from the Strip: in 2008-09, 2012, 2014, and 2021. There were also shorter Israeli military campaigns against the Gaza-based Palestinian Islamic Jihad (PIJ) in 2022 and 2023. In each of these conflicts, Israel would have been justified to enter Gaza and destroy Hamas in self-defense, but never felt so compelled—until Oct. 7.

It has been frequently reported that Israel, or at least its military intelligence agency, had a faulty strategic conception, the so-called “konceptzia,” that Hamas was deterred for now and more focused on governing Gaza than on attacking Israel. Many pundits in the Israeli and American media, who are overwhelmingly hostile to Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu, contend he was driven to prop up Hamas over the years with the help of Qatari money in order to divide the Palestinians and reduce pressure for a Palestinian state in the West Bank. Netanyahu, who has waged several wars against Hamas, has repeatedly denied this claim. While there have been plenty of leaks in the media already, Israeli military and government probes are expected to reveal what the military intelligence’s konceptzia was, what was motivating Netanyahu and other Israeli political and military leaders, and what contributed to the IDF inadequately preparing for, and/or ignoring signals of, a major Hamas attack.

In the meantime, it’s worth exploring why Israel did not invade Gaza and uproot Hamas from power years ago, based on the premise that Oct. 7 was not inevitable.

***

The threat from Gaza, however challenging, appeared increasingly manageable to most Israeli military and civilian leaders, despite the short wars with Hamas and PIJ. This misplaced confidence appears to have been partly driven by an overreliance on technology and missile defense. The 2011 deployment of Iron Dome, Israel’s 90%-plus-effective, short-range air defense system, seemingly minimized the rocket threat. With Iron Beam—a laser version that will be at the very least a powerful supplement to Iron Dome—soon to be deployed, Israel believed it was poised to have an even better counter to rockets fired from Gaza. One Israeli military expert told me a few years ago that once Iron Beam was deployed Israel won’t care what happens inside Gaza.

Hamas’ subterranean (tunnel) threat, which already seemed significant a decade ago, was thought neutralized with the installation along the border of underground sensors and barriers. Israel also believed it had neutralized the threat of a land invasion by installing an expensive fence with sensors and cameras. Moreover, the Israeli Air Force continued to operate at will in Gaza, often successfully killing Hamas and PIJ commanders and destroying terrorist infrastructure with precision strikes.

Secure in the belief that these measures had militarily neutralized the Hamas threat, Israel's civilian and military leaders were mostly averse to destroying Hamas and removing it from power in Gaza.

Israel remained loath to reoccupy Gaza, which it occupied in 1967 and from which it withdrew in 2005, out of concern that any attempt to do so would result in significant Israeli military casualties. Worse, it would bog Israel down in an unwanted occupation of Palestinians in what was viewed as a secondary or tertiary theater compared to the far more potent and immediate threat of Hezbollah to its north and Iran’s nuclear program. Also, Israel had tried its hand at shaping domestic Arab political arrangements in Lebanon in 1982, where it failed spectacularly, and its leaders opposed trying it again ever since. Further, Israeli leaders understood that such an effort in Gaza would be met by fierce international opposition. Indeed, it faced such opposition every time it launched a military campaign in retaliation for Hamas or PIJ firing rockets.

Moreover, when it comes to who could or would responsibly rule Gaza post-Hamas without threatening Israel, there simply never were serious candidates. Egypt did not want Gaza back after losing it to Israel in the 1967 war. Egyptian President Anwar Sadat wisely sought every inch of Sinai and not one inch of Gaza in Egypt’s peace agreement with Israel four decades ago. After the Palestinian Authority’s (PA) spectacular rout at the hands of Hamas two years after Israel’s withdrawal from Gaza, Israeli governments increasingly doubted they could rely on the PA to govern the Strip. The PA’s endemic mismanagement, corruption, and radicalism helped spawn overwhelming support for Hamas among its West Bank populace, and its financial rewarding of terrorism is especially anathema to the Israeli political right.

So Israel resigned itself to what some of its leaders call “managing the conflict.” That has meant “mowing the lawn,” or periodic military campaigns to degrade Hamas and PIJ after they conducted—or planned to conduct—rocket barrages, and facilitating economic assistance, in recent years from Qatar, when necessary. This wasn’t really a strategy, but a policy of making lemonade out of the available lemons. If Israel had no clear endgame it's because none existed, beyond perhaps waiting for Hamas to collapse one day. Still, the success of this approach depended on a basic, eminently achievable condition: the IDF’s ability to defend the 32-mile Gazan border. Of course, on Oct. 7, the IDF utterly failed to do just that, for reasons reported and to be determined.

Nevertheless, events since Oct. 7 largely corroborate Israel’s previous reluctance to topple Hamas from power in Gaza.

First, international support for Israel even after the savagery of Oct. 7 has cratered. Consider, for example, how President Biden has sought for months to prevent Israel from going into Rafah and finish off Hamas. Other Western leaders lost patience with Israel’s military campaign long before.

Second, Israel’s caution over casualties has been borne out. Israel has lost over 280 soldiers in its seven-month ground incursion into Gaza, with over 1,700 wounded. Those numbers are lower than expected but still remain a very heavy toll for a small country of 9 million. IDF deaths are the equivalent of almost 10,000 Americans, more than twice the number of U.S. soldiers killed in Iraq over eight years and more than three times those killed in Afghanistan over 20 years.

Third, Israel will need at least an additional year to continue to kill or imprison Hamas fighters once the intense fighting ends following a Rafah campaign. It also will need to maintain overall control of security of the Strip for an indefinite period.

Fourth, there’s no consensus or agreement on who should rule Gaza. Israeli leaders have been mum about who they think should govern the Strip, and have spoken of a long period of “deradicalization” before any putative non-Hamas Gazans can take greater control. Some, such as my colleague IDF Maj.-Gen. (ret.) Yaakov Amidror, former national security adviser to Netanyahu, attribute that partly to the "day after" not yet having arrived. As for Washington, although the Biden administration reportedly wants Gulf Arab states to be involved in the reconstruction and maybe even the security of postwar Gaza, it is unclear, assuming it goes anywhere, if the plan even intends to exclude or suppress Hamas.

Perhaps Israel could have pursued a middle course between acceptance and expulsion of Hamas governance in Gaza. It might have conducted more proactive actions against Hamas over the years to further degrade its military capabilities and prevent its smuggling activities. That would have required Egyptian help to halt, or at least minimize, the smuggling—to which Cairo clearly had turned a blind eye and from which it apparently has benefited financially. Perhaps Israel could have better controlled how international funding for Gaza was spent, to minimize Hamas using it for its terror infrastructure. It is unclear if any of these steps would have been realistic in light of U.S. policy toward the Palestinians (the exception of the Trump administration’s term, which paradoxically reinforced Israel’s inclination to stick with the status quo), and the IDF brass’s attachment to its technology-centered defensive posture.

***

In contrast, what is far more strategically problematic, yet less discussed, has been Israel standing by as Hezbollah vastly augmented its arsenal from about 10,000 rockets at the end of the 2006 war to today’s 150,000-200,000, plus several hundred precision-guided munitions and an array of Iranian-made attack drones. Few if any countries can match this arsenal, and it’s an order of magnitude greater than Hamas’ estimated 20,000 rockets and missiles stockpile on Oct. 7. Indeed, it is the more powerful Hezbollah in Lebanon, whose border with Israel had been generally quiet from 2006 until Oct. 7, that poses the far more potent strategic threat to the Jewish state, both in the damage it can inflict and the protection it offers Iran’s nuclear program.

A 2018 report by the Jewish Institute for National Security of America, an organization I head, stated that a vast majority of Hezbollah’s rockets are unguided and short-range, intended to be used “indiscriminately against northern Israeli towns and cities. But, unlike in 2006, Hezbollah now also has several thousand medium-range rockets and several hundred precision long-range missiles capable of striking targets throughout Israel.” At the outset of a conflict with Israel, Hezbollah would be capable of firing at least 3,000 rockets per day, and then settling in on 1,000-1,500 per day. In the 2006 war, Hezbollah fired 200 rockets per day.

This is a far greater challenge for Israel than Hamas, and Jerusalem has had no easy answer to this Hezbollah threat. In a war, Hezbollah could overwhelm the air defense capabilities of Israel, a small country with little strategic depth, causing unimaginable damage to strategic targets and population centers. Israel would have to determine which strategic sites and cities to protect and which to leave vulnerable and evacuate.

In fact, even short of a full-blown war, since Oct. 7, Israel already has been forced to evacuate tens of thousands of Israelis living near the Lebanon border. To prevent or mitigate such a catastrophe, Israel would be compelled to attack Hezbollah with tremendous force by land and air. Israel’s defensive posture in the north since 2006 has led to what had been unthinkable: Hezbollah imposing a depopulated zone inside Israeli territory.

The magnitude of Hezbollah’s capability has helped deter Israel, or give it pause, from attacking Iranian nuclear facilities. Indeed, Hezbollah’s rocket arsenal exists precisely to defend Iran and its most valuable nuclear assets by threatening to let loose against Israel should it ever target them. And now Iran is on the verge of becoming a nuclear threshold state, which is an unmitigated strategic disaster for Israel that could threaten its very existence. By playing it safe in Lebanon, Israel ended up in a worse situation on both fronts.

Years ago Israel could have launched a military campaign, not to destroy Hezbollah but to materially degrade its military capabilities. Israel would likely have needed to use ample ground forces and air power. It could have legitimized such an initiative upon enforcing United Nations Security Council Resolution (UNSCR) 1701, which marked the end of the Second Lebanon War in 2006. UNSCR 1701 prohibited “armed personnel, assets and weapons other than those of the Government of Lebanon and of UNIFIL,” and called for “disarmament of all armed groups in Lebanon, so that … there will be no weapons or authority in Lebanon other than that of the Lebanese State.” Those words—“the Lebanese State” and “the Government of Lebanon and UNIFIL”—should have made it clear from the get-go that an Israeli offensive campaign would be necessary not long after 2006. Instead, UNSCR 1701—and the accompanying U.S. policy of strengthening Lebanese state institutions—became a fig leaf for Iran to boost Hezbollah’s rocket and missile capability on Israel’s border.

The civil war in Syria, which started five years later, solidified Israel’s strategic blunder in Lebanon. As Israel's other neighbor to the north disintegrated, opening the door to an even larger Iranian footprint in the country than had already existed prior, the Israeli Air Force began targeting Iranian assets either in Syria or en route to Hezbollah in Lebanon. The IAF had virtually a free hand in Syria, an operational freedom that has continued even after Russia, with the Obama administration's acquiescence, established a military footprint in the war-torn country in 2015.

In August 2015, a few weeks after the signing of the Iran nuclear agreement, which seemed to some senior IDF leaders to take a war over Iran’s nuclear program off the table for a number of years, the IDF, under Chief of the General Staff Lt. Gen. Gadi Eisenkot, took the unusual step of publishing what the IDF called the “campaign between the wars” strategy. As Eisenkot wrote in 2019, after he retired, the new strategy “strives for proactive, offensive actions” intended to: “Delay war and deter enemies by constantly weakening their force buildup processes and damaging their assets and capabilities,” and “[c]reate optimal conditions for the IDF if war finally does come.”

This proactive strategy, of attacking Iran and Iran-backed forces to minimize their footprint in Syria and block their transfer of advanced capabilities to Hezbollah in Lebanon, was an implicit recognition of Israel’s huge failure in Lebanon. The IDF did not want Syria to become a much larger version of Lebanon. So Lebanon was put on hold, even as Hezbollah’s capabilities grew—along with U.S. investment in the country. The IDF’s “campaign between the wars” has been successful. Through hundreds of actions over the past decade, the IDF has prevented many transfers of advanced weaponry to Hezbollah in Lebanon, destroyed significant Iranian capabilities to manufacture weapons in Syria, and materially restricted the footprint in Syria of Iran and its militias. As an illustration of Iran’s ambitions in Syria, Tehran sought to amass 100,000 militia fighters in the country, but reportedly has only a fraction of that.

Israel didn’t apply to Lebanon the approach it took in Syria, where many outside actors were involved in a generally chaotic and conducive theater torn by a vicious civil war. While it would have certainly faced U.S. and international opposition, it would have been far less costly for Israel to conduct against Lebanese Hezbollah a version of a “campaign between the wars” shortly after 2006. With every passing year, the risks and costs of Israeli military action against Hezbollah have grown.

Israeli generals seemed convinced, or convinced themselves, that they could postpone facing this dilemma. They cited the mostly quiet Israel-Lebanon border as evidence that Hezbollah was in fact deterred. They often pointed to Hezbollah leader Sayyed Hassan Nasrallah admitting right after the 2006 war that had he known a Hezbollah operation against Israel, which killed three IDF soldiers and abducted two more, would “lead to a war at this time and of this magnitude … would I do it? I say no, absolutely not.” Maybe Hezbollah was deterred, or maybe Iran simply restrained its key proxy as it built it up to become critical dry powder in case Israel attacked Iran nuclear facilities—or both. Either way, the net result was still a drastic spike in Hezbollah’s military capabilities over the years. Hezbollah's enhanced lethality, coupled with increased American opposition to the “destabilization” of Lebanon—a de facto U.S. protective umbrella—in turn succeeded in forcing Israel to avoid launching campaigns inside its northern neighbor. At the very least, then, it can be said that the deterrence was mutual, which meant a net loss for Israel.

***

The current war of attrition which Hezbollah started with Israel after Oct. 7 possibly suggests Israel might have taken action against Hezbollah years ago without triggering a major war. Still, aside from the assassination of Hezbollah (and Hamas) commanders, Israel’s current efforts are mostly limited to destroying Hezbollah fighters and infrastructure within a few kilometers of the Israeli border. A major effort to degrade materially Hezbollah’s wider and more extensive capabilities would involve a far larger battlefield.

Apparently, there was no serious intention among Israeli civilian or military leaders over the past two decades to conduct such a campaign in Lebanon. Amidror attributes this partly to Israel losing its preemptive instinct.

Of course, Israel can’t go to war all the time, despite the myriad threats it constantly faces. Political leaders in this democratic country always need to balance addressing threats and ensuring security over the long term with the near-term need to maintain social stability, economic vitality, and growth. Indeed, Israel’s economy and wealth grew substantially since the Second Lebanon War; GDP was $158 billion in 2006, and more than tripled by 2022 to $525 billion, while GDP per capita grew from $22,494 to $54,930. That growth, while welcome, brought with it more complacency.

Until Oct. 7, Netanyahu, who has served as prime minister for most of the time since 2009, took pride in his keeping Israel mostly at peace and growing its prosperity. The opposition parties weren’t pushing for a preemptive campaign to degrade Hezbollah in Lebanon either. In fact, when a left-right coalition government ruled in 2021-22, it signed a maritime deal with Lebanon, with its then-Prime Minister Yair Lapid lauding the deal saying it “staves off” war with Hezbollah.

Since Oct. 7, Israel has sought to restore its shattered deterrence and security against the Iran-led axis, in Lebanon, Iraq, Syria, Yemen, and Gaza (for now), with Lebanese Hezbollah and its massive arsenal its chief guardian. Iran is on the verge of crossing the nuclear threshold as it advances its weaponization program. Israel will soon face the decision whether to initiate a major military action to degrade Hezbollah in Lebanon and remove it as a strategic threat, and whether to attack militarily Iran’s nuclear program. Israel will need some American backing—politically at the U.N., and militarily by supplying it with some of the weapons it will need for such campaigns, and to help mitigate the scope and intensity of the blowback. Of course, Israel will need to take into account that the Biden administration, whether it lasts another eight months or five years, will oppose such an endeavor. Indeed, the administration has been very vocal against any conflict with Iran or Hezbollah.

Despite some similarities, the Hamas and Hezbollah challenges to Israel were not the same prior to Oct. 7 and required different policies.

In Gaza, Israel opted not to destroy Hamas but to “manage the conflict,” whereby it degraded Hamas’ military capabilities occasionally during military operations or limited wars. This strategy helped lull Israel into a false sense of security that resulted in the deadliest terrorist attack in Israel's history. With Hezbollah, which controlled a larger area in Lebanon than Hamas did in Gaza, and is far more essential to Iran’s security and regional strategy, Israel did not even try, in the years after 2006, to degrade its capabilities through a significant military campaign, or campaigns. Instead, Israel chose to do little inside Lebanon, mostly focusing on limiting the growth of Hezbollah’s capabilities through a decadelong campaign in Syria.

Oct. 7 will go down as a catastrophic intelligence and military failure. However, Israel allowing the Hezbollah threat to metastasize over the past two decades appears to have been a colossal strategic blunder, the cost of which could even dwarf that of Oct. 7. For Jerusalem, the Lebanon bill is past due.

Trump's 34 felony counts made it into court, where he got convicted. He set a record. Isn't this the egomaniac who wants to break records every day? So he should be happy. He set yet another record; that of being the first President dumb enough to get caught. No worries to all politicians on both sides of the aisle; from now on every effort and tax dollar shall be spend to catch every other President on something, so that we can keep the lawyers busy. Remember Kenneth Starr? Who, between the mid to late-nineties spent over 95 million of our tax dollars researching the Clintons. 6.5 million alone on a blow job controversy by a women in a blue dress. Impeachment became the tit for tat. As of last week, that will go up a notch. Courts get ready.

See here https://www.dailywire.com/news/verdict-trump-found-guilty-on-all-charges-in-hush-money-case?topStoryPosition=1lAnyone who litigates in the NY State Courts knows that the Appellate Division, the intermediate appellate court and the Court of Appeals, the highest court in the state, are not Trump''s best hope for a reversal and dismissal; of a conviction. Trump probably will exhaust his pre and post appeal remedies in NY and seek review by SCOTUS of the massive constitutional infirmities and violations in this conviction, or seek an expedited review by SCOTUS .